Why we’ve filed complaints against companies that most people have never heard of – and what needs to happen next

Today, Privacy International has filed complaints against seven data brokers (Acxiom, Oracle), ad-tech companies (Criteo, Quantcast, Tapad), and credit referencing agencies (Equifax, Experian) with data protection authorities in France, Ireland, and the UK.

It’s been more than five months since the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) came into effect. Fundamentally, the GDPR strengthens rights of individuals with regard to the protection of their data, imposes more stringent obligations on those processing personal data, and provides for stronger regulatory enforcement powers – in theory.

In practice, the real test for GDPR will be in its enforcement.

Nowhere is this more evident than for data broker and ad-tech industries that are premised on exploiting people's data. Despite exploiting the data of millions of people, are on the whole non-consumer facing and therefore rarely have their practices challenged.

Most people have likely never heard of these companies, and yet they are amassing as much data about us as they can and building intricate profiles about our lives. GDPR sets clear limits on the abuse of personal data and yet these companies’ practices are failing to meet the standard. Our complaints document wide-scale and systematic infringements of data protection law.

From an advocacy and policy perspective in particular, a number of our findings are especially relevant.

Abuse of legitimate interest as a legal basis

A recurring pattern in our complaint is that companies rely on legitimate interest as a legal basis on their processing operation in ways that are incompatible with the requirements set out in the GDPR.

The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has described legitimate interest as the most ‘flexible’ legal basis. However, this does not mean that it is without limits or can be moulded exactly to fit or justify any processing operation. The processing must meet a three-part test. The data controller must identify a legitimate interest (purpose); show that the processing is necessary to achieve it (necessity); and balance it against the individual’s rights and freedoms (balancing).

Legitimate interest cannot be equated to the interest of companies to make a profit from our personal data. But that is what some of the data broker companies seem to believe. Our complaint aims to challenge this interpretation and to limit reliance on legitimate interest, in line with the ICO’s guidelines.

The importance of profiling and data protection principles

Companies that engage in profiling need to make sure that such profiling complies with the Data Protection Principles, in particular transparency, fairness, purpose limitation, data minimisation, accuracy, and the requirement for a lawful basis (including for special category personal data).

Yet, our complaint shows that many companies fail to comply with basic Data Protection Principles or even seem to work under the assumption that derived, inferred and predicted don’t count as personal data, even if they are linked to unique identifiers or used to target individuals.

A new aspect of GDPR is an explicit definition of profiling in Article 4(4):

“any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person, in particular to analyse or predict aspects concerning that natural person’s performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behaviour, location or movements”.

Disparate and seemingly innocuous data can be combined to create a meaningful comprehensive profile of a person. Advances in data analytics, as well as machine learning have made it possible to derive, infer and predict sensitive data from ever more sources of data that isn’t sensitive at all. For instance, emotional states, such as confidence, nervousness, sadness, and tiredness can be predicted from typing patterns on a computer keyboard. The very same techniques have made it easier to de-anonymise data and to identify unique individuals from data about their behaviour across devices, services and even in public spaces. Such profiles may allow users of the data to infer highly sensitive details that may or may not be accurate and that can by inaccurate in ways that systemically mischaracterise or misclassify certain groups of people.

Data brokers, ad tech companies, and credit referencing agencies amass vast amounts of data from different sources (offline and online) in order to profile individuals, derive, and infer more data about them and place individuals into categories and segments.

Profiling is so central to the operation of data brokers, that the Article 29 Working Party uses data brokers as examples to explain profiling:

“A data broker collects data from different public and private sources, either on behalf of its clients or for its own purposes. The data broker compiles the data to develop profiles on the individuals and places them into segments. It sells this information to companies who wish to improve the targeting of their goods and services. The data broker carries out profiling by placing a person into a certain category according to their interests.”

Because profiling can be done without the involvement of individuals, they often don’t know that whether these profiles are accurate, the purposes for which they are being used, as well as the consequences of such uses.

Our investigation shows that many companies fail to comply with data protection principles.

The importance of data rights as investigative tools

Privacy International’s investigation into the data practices of these companies was three-fold: we analysed the companies’ privacy policies pre- and post-GDPR, we conducted research on the companies’ publicly available marketing materials and we submitted data subject access requests by members of our team.

Even though the responses we received were limited, and in many cases incomplete, they were useful in providing a deeper understanding of the ways in which these companies process personal data. This shows how crucial enforceable data rights, and the right to information in particular, is to hold companies to account. This is something that every individual is entitled to, and a number of non-profits have developed tools to facilitate access requests: from PersonalData.io, MyDataDoneRight by Bits of Freedom in the Netherlands, to the Datarightsfinder by the Open Rights Group and Projects by IF in the UK.

Companies need to ensure that they comply with the right to information in full and don’t make the process unnecessarily bureaucratic.

The need for collective redress

Breaches of data protection law by non-consumer facing companies like data brokers and ad tech companies shows how illegal data-related activities are often hidden from individuals. Most people do not know that the companies we have investigated process their data and profile them, whether this data is accurate, for what purposes they are using it, or with whom it is being shared and the consequences of this processing. That’s why people need qualified non-profit organisations to take independent action when they consider that there has been a failure to comply with data protection law.

While the GDPR provides for individuals to mandate NGOs to take legal action on their behalf, the provision for collective redress was left to EU member countries decision, and the UK decided not to implement it, despite this issue being one of the most hotly debated at all stages of the Bill.

We urge all EU member states to implement Article 80.2 of GDPR which allows qualified non-profit organisations to take independent action when they consider that there has been a failure to comply with data protection law.

Going forward

The data protection infringements we observed are very serious and systematic. Nonetheless, they merely constitute the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of the companies’ data practices. That’s why we’ve sent our requests to data protection authorities across Europe, asking them to investigate these companies’ practices in their countries.

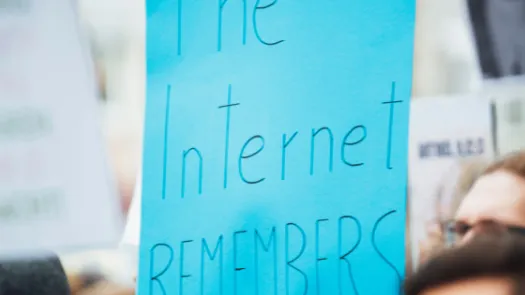

The world is being rebuilt by companies and governments so that they can exploit data. Without urgent and continuous action, data will be used in ways that people cannot now even imagine, to define and manipulate our lives without us being to understand why or being able to effectively fight back.

We encourage journalists, academics, consumer organisations, and civil society more broadly, to further hold these industries to account.