Statement before the European Parliament hearing on "Spyware and ePrivacy"

On 26 October 2022, PI gave evidence for a second time before the EP Committee of Inquiry to investigate the use of Pegasus and equivalent surveillance spyware.

- In this hearing which focused on 'Spyware and ePrivacy', our intervention first discussed whether current ePrivacy directive can apply to the use of spyware by state authorities, including how states often use 'national security' to exclude surveillance measures from the ambit of EU law.

- Second, we emphasised why government authorities deploying spyware tools might never be able to demonstrate their compliance with EU and international human rights laws.

- Finally, PI offered a series of recommendations that the Committee should adopt in order to safeguard everyone's rights against these extremely intrusive surveillance tools.

PI Opening Statement at PEGA Hearing on "Spyware and ePrivacy"

[check against delivery]

Thank you very much for offering us the opportunity to give evidence before this Committee for a second time.

Privacy International (PI) is a London-based non-profit that researches and advocates globally against government and corporate abuses of data and technology. For years we have been tracking the surveillance industry, challenging unlawful surveillance before national courts as well as the Court of Justice of the EU and the European Court of Human Rights.

My opening statement will first briefly touch on the obligations the ePrivacy directive imposes on service providers and states, as well as the national security exemption. Second, it will explore the question whether the Directive can apply to the use of spyware by member state authorities and, accordingly, trigger the applicability of the EU fundamental right guarantees. Finally, I will provide a series of recommendations by PI that seek to assist this Committee in strengthening the rule of law and upholding the rights of millions of individuals living in the EU.

First of all, what we refer to as ePrivacy is the EU Directive 2002/58, and its subsequent amendments, which protects the confidentiality of communications and lays down rules regarding tracking and monitoring. These ePrivacy laws should be considered as complementary to other EU laws concerning the protection of personal data, namely the GDPR.

Among others, the ePrivacy Directive seeks to impose obligations on communications service providers to ensure the security of their services, while it also requires member states to adopt laws that guarantee the confidentiality of communications. Accordingly, a measure taken by national authorities that allows them, for example, to access data held by communication service providers would limit the ePrivacy protections. It would also constitute an interference with the rights to privacy and the protection of personal data.

Article 15 of the Directive does allow for such restrictions in the form of legislative measures adopted by member states. They need to be tailored to specific aims, such as the prevention or detection of crime, and need to meet certain criteria laid down by the Directive and, more generally, EU human rights law, such as necessity and proportionality.

This will also be the case even if the measures adopted by member states pertain to national security purposes, despite the fact that several member states, including Poland and Hungary, have in the past sought to exclude them from the ambit of EU law by relying on Article 4 paragraph 2 of the Treaty of the European Union.

Recently, in a case brought by PI, the Court of Justice clarified that national security measures imposing data retention obligations on service providers would still fall under the ePrivacy Directive because they would require the processing of data by service providers.

According to the Court, the crucial element is whether member states are imposing processing obligations on companies. In other words, in order to provide access to the data held by them, communication service providers would still have to process them in accordance with their obligations under the ePrivacy Directive which confirms that EU law still applies even in the context of such measures.

This brings me to my second point: the crucial issue, according to the case-law, seems to be the processing of data by service providers. Spyware, however, as we know, does not always require the involvement of providers of electronic communications services. Could the ePrivacy Directive still be relevant for the use of spyware by national authorities of member states?

First, Article 5 of the ePrivacy Directive, widely known as the cookie provision might help answer this question in the affirmative. Paragraph 3 of that Article prohibits the storing of information and, perhaps more crucially, the access to information already stored on the devices of users without their consent. However, this approach has not been tested in courts yet and it would be interesting to see what stance the CJEU will follow in a preliminary question referred to it recently by an Austrian court.

Second, if one takes a wider, teleological interpretation of the ePrivacy Directive and the rights it seeks to protect, it could be perhaps argued that the deployment of spyware would somehow still involve the passive involvement of communication service providers as the devices infected would be running on their networks and as mentioned earlier the Directive requires them to take adequate measures to ensure the security of such networks.

What further adds to this legal uncertainty is the fact that these rules are contained in a Directive, and not a Regulation, which means that to a certain extent they are subject to member state discretion in how to transpose or enforce them. A similar situation has been observed by Privacy International with regard to provisions mandating data retention. In 2017, we surveyed 21 EU member states' legislation on data retention and examined their compliance with fundamental human rights standards. Out of the 21 member states we examined, none was then found to be compliant with the standards set by the Court of Justice of the EU in two landmark judgments, Tele-2/Watson and Digital Rights Ireland.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that regardless of the applicability of the ePrivacy Directive, the use of spyware by member states might still be governed by other EU law instruments, such as the the Law Enforcement Directive, or international human rights law such as European Convention on Human Rights and Convention 108. Considering the extremely intrusive nature of spyware tools and the dangers they pose for the security of both individuals as well as the Internet as a whole, we believe that the deployment of such tools, as we have seen with Pegasus, violates the essence of the right to privacy and the protection of personal data and as may never be able to be compatible with human rights laws.

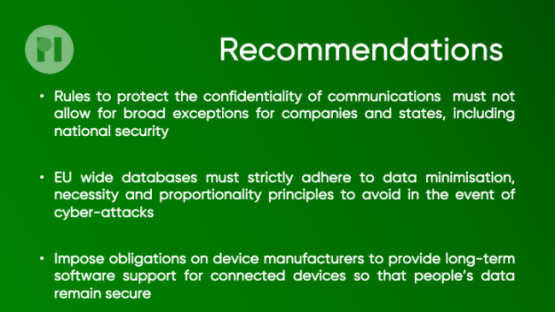

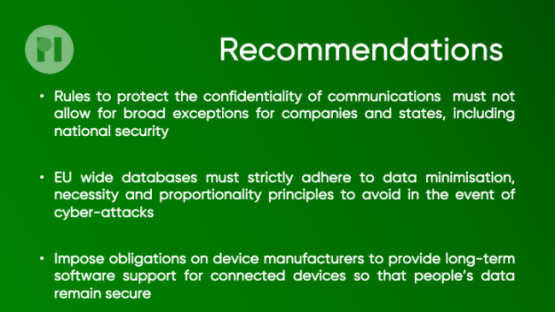

Finally, with regard to what the EU should do, there are 3 recommendations that we urge you to adopt.

First, it vital that any new legal instruments that seek to protect the confidentiality of communications provide for robust guarantees and even more robust enforcement. Notably, any national security exemption must be strictly applied, especially when the rights of individuals are engaged in the context of mass surveillance or government hacking. To paraphrase the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights, measures that seek to protect national security can "undermine or even destroy democracy under the cloak of defending it". Moreover, this Parliament should refrain from adopting proposals that seek to undermine one of the best defenses against surveillance, encryption, by pursuing well-intentioned but flawed policies, such as those contained within the Commission's Proposal on combating Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM).

Second, proposals that seek to establish EU-wide databases, such as data retention, should prioritise strong security to protect personal data. They should ensure the collection of data is minimised and retained only for the shortest time necessary for the purpose. This is not only due to the several issues they raise with regard to their compatibility with human rights laws, but also due to the threats they present for the [security of everyone's data]. Incidents, like the WannaCry and NotPetya cyber attacks, stemmed from the exploitation of similar vulnerabilities and escalated to compromising European infrastructure operators in the sectors of health, energy, transport, finance and telecoms.

Third, the EU should mandate long term software support for connected devices. Our research has revealed how existing practices of device manufacturers around security updates fail to meet the expectations of the vast majority of consumers. At the moment, there are two important legislative proposals discussed in Parliament, the Directive on empowering consumers for the green transition and the EU Cyber Resilience act. It is imperative that both of these texts ensure that people's devices do not become vulnerable to malicious attacks.

In sum, PI believes that this Committee is presented with a unique opportunity to uphold the fundamental rights of millions of citizens. We are confident that it it will live up to its challenging task and promote democracies, where people are free to be human both offline and online.

Thank you for your attention and I am looking forward to your questions.

[You can watch the hearing here]