ID systems analysed: DNIe in Peru

This piece was written by Privacy International, based on publicly available information and on research by our partners at Hiperderecho

Overview

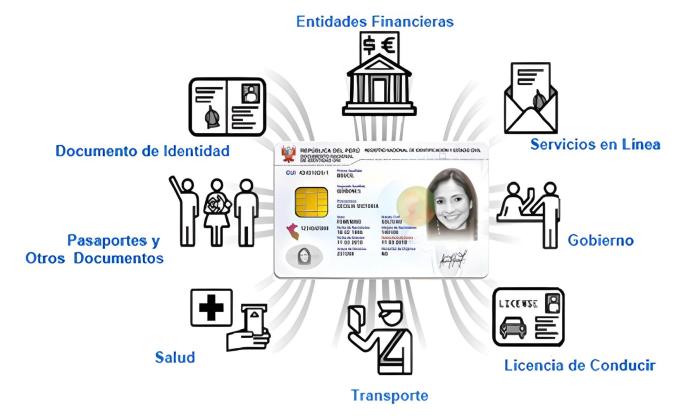

The Documento Nacional de Identidad (DNI) is the personal ID card recognised by the Peruvian State in any situation where a person might have to identify themselves, be it in an administrative, judicial, civil, or commercial context. The DNI also grants its holder the right to vote.

The DNI issuing and overseeing body is the Registro Nacional de Identificación y Estado Civil (RENIEC).

While the original DNI was implemented in 1997, an electronic version (DNIe) has been slowly replacing it since 2013. The new card contains the same information inprinted in it as its predecessor, but in addition it has a chip that stores that same data and more.

The card integrates a series of physical security features including a map of Peru printed with optically variable ink, a hologram, microtext and guilloché pattern. The card also incorporates four software applications: the first identity eMRTD ICAO, the second digital signature PKI, the third biometric authentication by Fingerprint Match-on-Card and a generic type room that includes data storage and Counter devices.

The card is compulsory and expires every 8 years, with citizens required to renew and update their details. After the age of 60 citizens are no longer required to renew their IDs. Presentation of the card is required in order to be able to vote, with no other alternatives being accepted at polling stations.

Since 2001, Peru's identification programme also includes the provision of a DNI for children. This mandates that children are registered so that they can access different public social services. This initiative, primarily justified at avoiding exclusion from social programs, can very well have the opposite effect and contribute to systemic exclusion, especially in poorer rural contexts where the Child DNI registration gap is the greatest.

Infrastructure Makeup

Peru's ID system relies on Digital ID registries, of which RENIEC keeps physical backups in its centralised archives in Lima and Arequipa. Although these massive databases are deployed in a centralised way, according to the World Bank there are still no explicit norms or guidance to safeguard the privacy or security of the information being stored in these ID registries.

Characteristics of the microchip

- Java Card operating system, which enables the incorporation of future applications and content.

- Cryptographic capacity for RSA key management and digital signature with certificates.

- EEPROM memory of 144 Kb.

- Security according to the international standards Common Criteria level EAL4 + or FIPS 140-2.

- Basic Access Control (BAC), which prevents unauthorized access to the content of the chip.

- Active Authentication (AA), RSA key of 1024 bits that guarantees the authenticity of the chip and prevents its cloning.

- Applications: PKI, ICAO eMRTD, Match On Card (MOC).

- Complementary software: Middleware, SDK for client applications, Java Card SDK

Certificates included

- Root certificate of the National Certification Entity of the Peruvian State - ECERNEP

- Digital certificate of the Certification Entity of the Peruvian State - ECEP

- Digital certificates of the citizen

Information shown on the electronic ID

In a similar way to the previous DNI, the DNI-e contains the following information:

- CUI number (Unique Identification Code)

- First surname (paternal surname)

- Second surname (maternal surname)

- Other names

- Sex

- Civil status

- Date of birth

- Place of birth (code of the department, province and district)

- Date of issue

- Date of expiration

- Voting group - this is assigned by RENIEC to all voters. ID card holders who have not been assigned a voting group have no judicial capacity.

- Organ donation

- Photo

- Signature

- Right index fingerprint

- Department, province and district of housing

- Address

Biometrics

The collection of fingerprints from both index fingers and a picture of the person's face is mandatory. In case a person’s fingerprints are damaged or absent, they need to obtain a certificate from RENIEC stating their condition.

Authentication and De-duplication

The Peruvian ID system relies on three main sources of information to verify the identity of the holder: a picture of the person's face, their fingerprint and signature.

RENIEC's Identification Registry department is responsible for performing updating, de-duplication, authentication and clearance functions. In order to perform de-duplication and ensure that new entries in the system are unique and authentic RENIEC carries out:

- automatic fingerprint identification, which compares the input fingerprint with the millions of other fingerprints previously stored in the database.

- dactylographic check (from signature records)

- facial recognition checks.

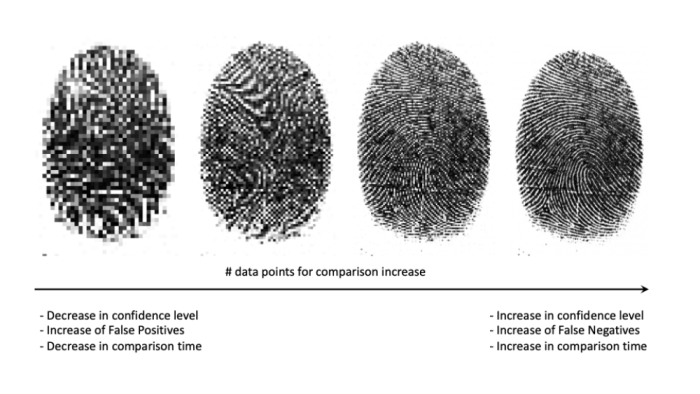

Official documentation states that the 'Match-on-Card' application that does fingerprint de-duplication is configured with ideal parameters to yield the best results in terms of response time, false positive rates and false negative rates.

For context, these parameters are used to increase or decrease confidence levels in biometric comparisons, in order to try and achieve a balance between guaranteeing biometric uniqueness and being able to do so in an adequate time frame, which jeopardises the principle of uniqueness in itself. Biometric matching is always done within a certain interval of confidence as a baseline, meaning the authority performing the check can only claim "we are X% sure that this is the person" rather than "We are absolutely sure that is the person".

We have written about how tweaking parameters for biometric identification is a number's game which can tamper with the endgoal of identification. You can learn more about this topic and on how large populations make it virtually impossible to guarantee biometric uniqueness in the context of national identity by reading our analysis into Aadhaar in India.

Principles of Engagement

RENIEC developed Peru's electronic DNI -the first of its kind in Latin America - as one of the components that would help the country achieve the strategies stated in its Digital Agenda, such as:

- Promoting interoperability between state institutions for cooperation, development, integration and the provisioning more and better services for society.

- Providing the population with information, procedures and public services accessible by all available means.

- Developing and implementing mechanisms to ensure timely access to information and citizen participation as a means to contributing to the governance and transparency of state management.

- Implementing mechanisms to improve information security.

- Improving the capacities of both public officials and society to access and make effective use of e-government services.

- Adapting the necessary regulations for the deployment of electronic government.

Countries at use

Peru

Examples of Abuse

Social Protection benefitiaries identification

Balancing compliance with data protection standards while ensuring transparency about the usage of identification information for social protection services is a delicate process. In Peru, the authorities responsible for social protection programmes access identification databases and require certain identification, such as the presentation of a DNI, to provide services. Eligibility and enrollment criteria are based on identification data as well as factors such as income, home address, and other personal conditions (i.e. disabilities, victims of violence, number of children, etc.). In general, these databases should adhere to strict confidentiality standards as they contain sensitive personal information that can lead to stigmatization and discrimination, or put beneficiaries at risk of personal security issues. What happens is quite the opposite, with social programmes regularly releasing lists of beneficiaries in the interest of transparency, which can lead to the aforementioned discrimination.

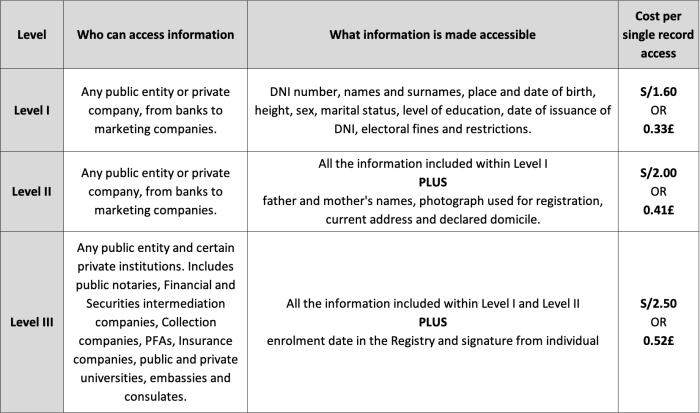

Sale of identification data to government and corporate entities

Additionally, according to research by Hiperderecho, RENIEC sells access to the personal data collected for the purpose of identification within its national identity system to a variety of third parties (see below). The information that RENIEC holds on DNI holders is categorised in three different levels, each of them with a different access cost but none out of them completely out of reach.

Placing a paywall in between institutions and the personal data of the Peruvian population does not guarantee the much needed safeguards for this all-encompassing and sensitive data. Specially when this data has a strong discriminatory potential such as a person's educational backgrounds or disabilities.

Besides payment, the one other formal ~~requirement~~ mechanism to access such data is for public and private institutions to sign an agreement with RENIEC explaining how their line of business justifies access to people's data while also committing to keep the information confidential and not resell or distribute it to any third parties. Beyond this agreement, it appears that there is little RENIEC can do in practice to monitor and prevent abuses.

Platform vulnerabilities

As reported by our partners at Hiperderecho, back in 2018 there was a vulnerability in a system developed by RENIEC for the Ministry of Health which was used in the country's health centers to check the health of children under 6 years of age. This vulnerability allowed for anyone to download the ID picture from of any Peruvian citizen. And because the numbers used for the DNI are sequential, it also meant that it was possible for an attacker to create an automated tool to basically download what our partners at Hiperderecho described as "the most complete photo album in Peru".

Potentially exclusionary assignment of 'Voting Groups'

Another factor that has demonstrably affected and excluded Peruvian citizens from their right to vote is the assignment of "voting groups" to citizens deemed 'fit to vote' and the exclusion of all those who in the eyes of the state, aren't. While voting groups are assigned by RENIEC, individuals can be excluded based on their circumstances. One of the processes by which individuals are prevented from being assigned a voting group is judicial interdiction, i.e. the process by which a judge declares a person either partially or absolutely lacking mental capacity. Once an interdiction is made, as often is the case for example for people with disabilities, the person concerned is locked out of their civil rights, is deemed to lack legal capacity, and a representative is appointed on their behalf. Interdiction remains one of the legal bases for people with disabilities to receive state benefits. This has led to cases where people with disabilities have had to choose between declaring their status to the government in order to get much needed benefits (pensions and assistance) or not declare their status in order to be able to continue vote. Once an interdiction is made, it invalidates a lot of the subjects rights with immediate effect. This is a choice that no one should be forced to make and that is exclusionary by nature.

Despite Digital IDs being pushed as aiding in development and inclusion, their actual implementation isn't without shortcomings which can have very real and impactful negative consequences on individuals such as the ones described above. Combining identification, financial and biographic data (such as level of education or assignemnement of voting groups) can pose serious risks for individuals in case of a breach, such as exclusion from welfare programs, access to credit or even exclusion from voting. On top of this, sharing identification data with any sort of institutions - public or private - without clear, informed and expressed consent from users can also work towards perpetuating inequalities rather than helping to curb them.