Push This Button For Evidence: Digital Forensics

We look at the recently published report on forensic science in the UK, highlight concerns about police not understanding new tech used to extract data from mobile phones; the risk of making incorrect inferences and the general lack of understanding about the capabilities of these tools.

The delivery of justice depends on the integrity and accuracy of evidence and trust that society has in it. So starts the damning report of the House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee’s report into forensic science in the UK. Gillian Tulley, Forensic Science Regulator describes the delivery of forensic science in England and Wales as inadequate and ‘lurching from crisis to crisis’. The report issues stark warnings in relation to digital evidence and the absence of ‘any discernible strategy’ to deal with the ‘rapid growth of digital forensic evidence’.

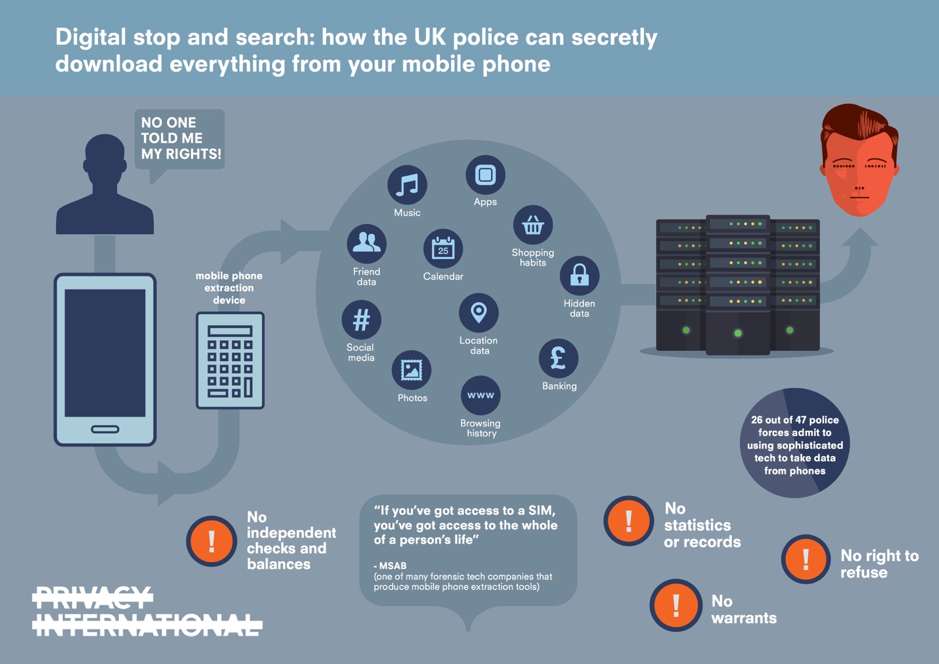

Use of mobile phone extraction [to obtain digital evidence] is arguably the most intrusive form of technology used by the police and relates not just to the data of the user of the phone but also those of the many other people who have communicated with the user.

Privacy International's 2018 report 'Digital Stop and Search' found that frontline police officers have been using mobile phone extraction tools to obtain the personal data of victims, witnesses and suspects for all types of crime, since at least 2012.

Despite having had years to ensure that their use of powerful technologies to extract, analyse and present data contained on mobile phones is done in a way which not only respects individual privacy but is attuned to security risks, they have failed. The outrage over new victim consent forms, which allow police to access deeply personal data from mobile phones of rape survivors is arguably one of the police’s own making given the secrecy surrounding mobile phone extraction; the absence of local and national guidance; the lack of clarity on what basis it is actually lawful; and the failure to consult the public to date.

Trust

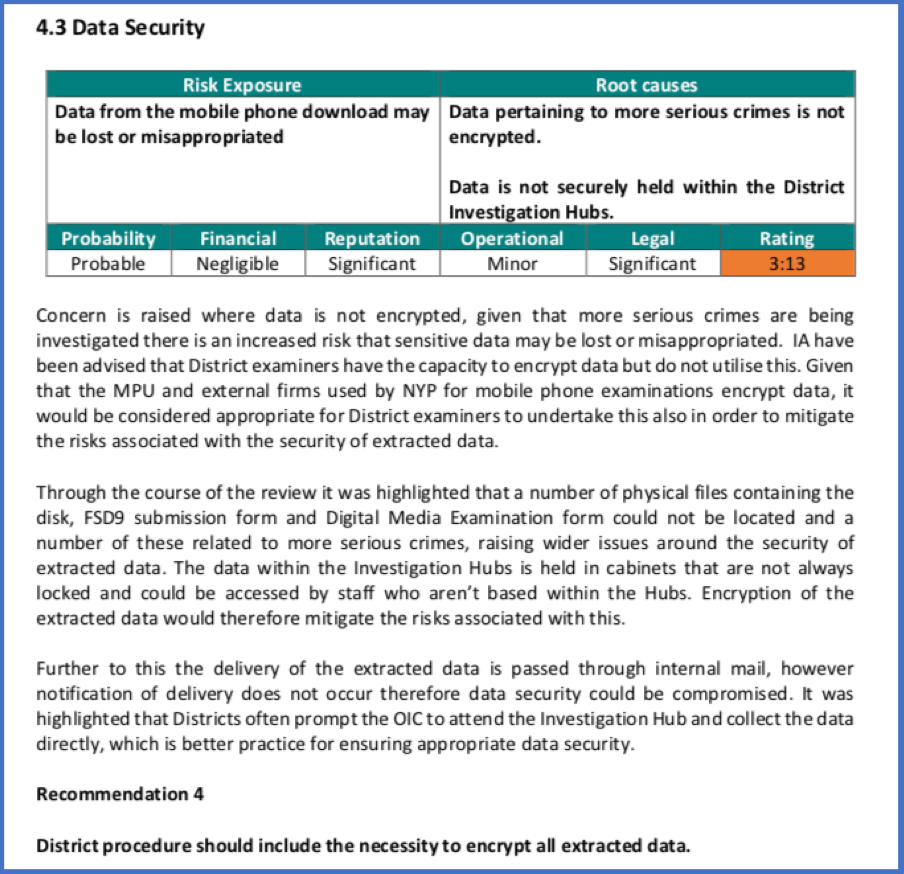

If we are to entrust vast amounts of highly personal data to the police, not only should the lawfulness of extraction be clear and accessible, but we also want to know they have good security and detailed security policies and procedures in place, specifically for mobile phone extraction. As part of security risk analysis, we also need to know that they understand these technologies.

And yet, despite threats to information security worsening each year, and the obvious point, noted by National Cyber Security Centre that “bulk data stores make very tempting targets for attackers of all kinds", the evidence to the Committee and findings indicate that more questions need to be asked about the deployment of extraction technologies and what security controls are in place.

Data breaches happen due to poor implementation or complete absence of security controls. The police are no strangers to appalling data breaches through their own fault and have received a number of fines from the Information Commissioner. Gloucestershire Police were fined £80,000 in 2018 for revealing identities of child abuse victims. As for security controls, the criticism of North Yorkshire police failing to encrypt data despite having the capacity to do this, is deeply concerning.

But whilst the volume and retention of data are fundamental, there are wider security issues. As noted by Bruce Schneier:

“Security is complicated and challenging. Easy answers won’t help, because the easy answers are invariably the wrong one. What you need is a new way to think.”

Accuracy of evidence: Do the police know what they’re doing?

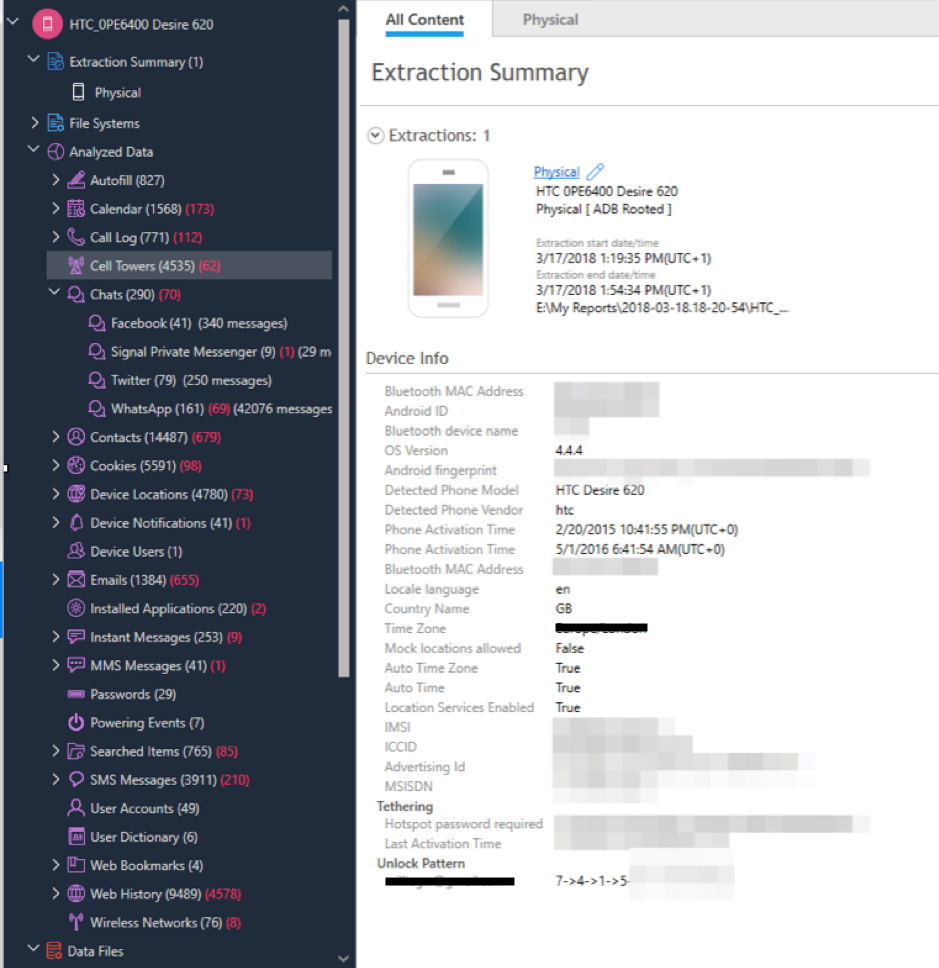

Police officers who operate mobile phone extraction technologies often have little or no forensic training and are increasingly reliant on devices whose capabilities they do not understand, particularly as budgets are cut and the volume of data they have to cope with increases.

Forensics experts have highlighted that heavy reliance on easy to use tools which grab data off a phone “by pushing some buttons” dumbs down digital forensics examinations and could undermine the successful examination of mobile phones. On this front, the hearings of the Science and Technology Committee made for concerning reading.

Dr Jan Collie, Managing Director and Senior Forensic Investigator at Discovery Forensics, highlighted to the Committee the lack of forensic skill by those using MPE technology:

“What I am seeing in the field is that regular police officers are trying to be digital forensic analysts because they are being given these rather whizzy magic tools that do everything, and a regular police officer, as good as he may be, is not a digital forensic analyst. They are pushing some buttons, getting some output and, quite frequently, it is being looked over by the officer in charge of the case, who has no more training in this, and probably less, than him. They will jump to conclusions about what that means because they are being pressured to do so, and they do not have the resources or the training to be able to make the right inferences from those results. That is going smack in front of the court.”

Dr Gillian Tully, UK Forensic Science Regulator commented that:

“There is a lot of digital evidence being analysed by the police at varying levels of quality. I have reports coming in in a fairly ad hoc manner about front-line officers not feeling properly trained or equipped to use the kiosk technology that they are having supplied to them.”

The Serious Fraud Office argues to the Committee that there is a need for more regulation, or a mechanism by which agreed criteria and standards are adhered to as digital evidence became more ubiquitous in criminal trials. The ‘provenance and integrity of material obtained from digital devices is a key area’, they said.

Integrity of evidence: What can the tech do?

In the world of digital forensics, write digital forensic scientist Angus Marshall and computer scientist Richard Page, both of the University of York, we tend to rely on third-party tools which we trust have been produced in accordance with good engineering practices. If we consider mobile phone extraction, the examination starts with a phone whose contents are unknown, thus, “inputs to the whole forensic process are unknown”. This impacts on whether it is possible to identify when something has gone wrong with the so-called evidence. They state that:

“It is entirely possible for a tool to process inputs incorrectly and produce something which still appears to be consistent with correct operation. In the absence of objective verification evidence, assessment of the correctness, or otherwise, of any results produced by a tool relies solely on the experience of the operator.”

“It should also be borne in mind that updates to hardware and software may have no apparent effect on system behaviour as far as a typical user is concerned, but may dramatically change the way in which internal processing is carried out and data is stored.”

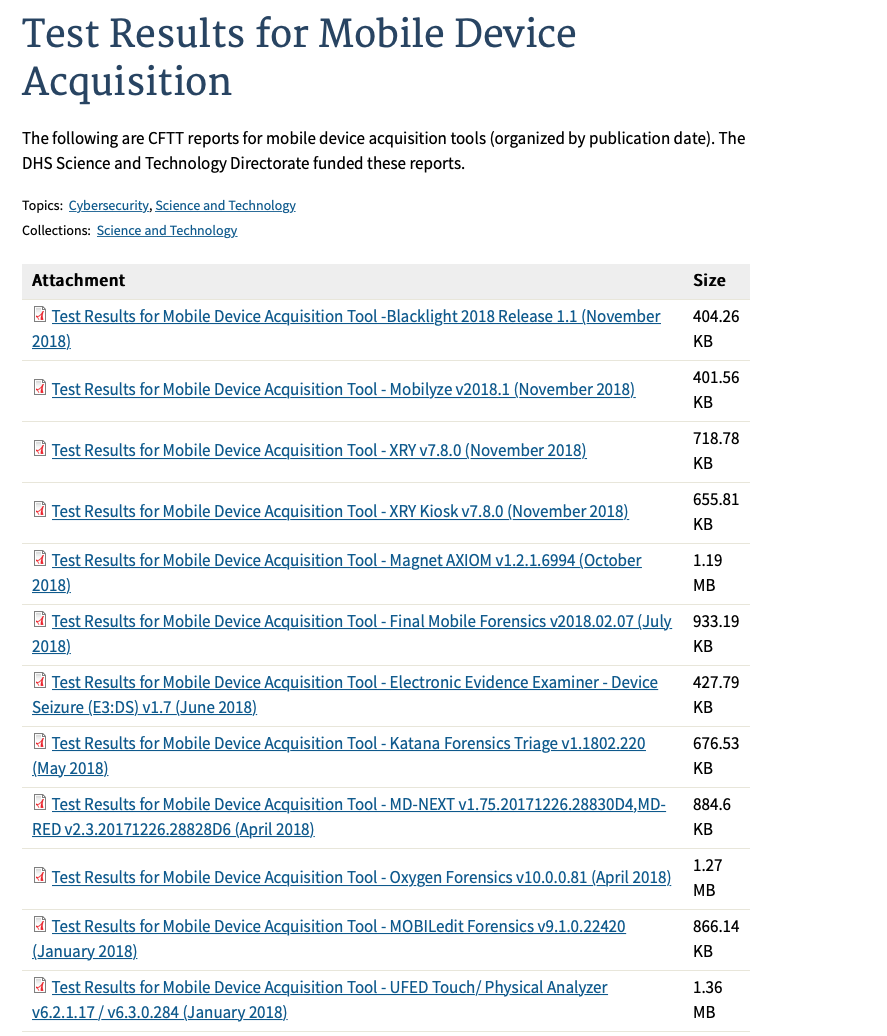

In the US, the National Institute of Standards and Technology have a Cyber Forensics project to provide forensic tool testing reports to the public. Their tests have revealed, according to MobileEdit, that there are significant differences in results between individual data types across the competitive tools tested. Each tool was able to demonstrate certain strengths over the others, and there is no single tool that demonstrated superiority in all testing categories.

In the UK there is no testing of devices purchased by law enforcement. Forensic Regulator Dr Gillian Tully, commented that:

“As yet, those [mobile phone extraction tools] have not all been properly tested…”

Dr Jan Collie also noted:

“Most of the forensic tools we use are tested to within an inch of their lives by the companies who produce those tools. We are not allowed to reverse engineer them [digital forensics tools] because that would be illegal anyway.”

One explanation for the lack of testing relates to claims of commercial confidentiality. But as Angus Marshall commented to the UK Select Committee:

"private providers are unwilling to disclose information about their own development and testing methods [which] means that the evidence base for the correctness of many digital methods is extremely weak or non-existent.”

Ignorance of the way these tools work is dangerous to the proper functioning of the criminal justice system. It is essential “that there is disclosure so that the methods used are open to scrutiny and peer review of its accuracy and reliability”.

Sir Brian Leveson alerted the Committee about a case in which:

“The contents of a phone had been wiped … and there were great difficulties finding out what had been on the phone. However, a commercial provider managed to download or retrieve some of the messages. The defence wanted to know how they had done that and the scientist was not prepared to explain it, first, because it was commercially confidential and, secondly, if he explained how he had done it, the next time round they would find a way of avoiding that problem.”

A recent update from one extraction company, Magnet Forensics, exemplifies the problems that stem from a lack of awareness about the capabilities of mobile phone extraction tools, to the point that they can do things that are unlawful, but without the police officer realising this.

“When we introduced Magnet.AI, it ran automatically when you opened your case in AXIOM Examine... this could be a problem in some cases: if it revealed evidence that was outside the scope of your warrant … risk the admissibility of all the evidence on the device.”

Inadequate approach to risk : Remote access & cyber security

One area the Committee did not touch upon was the ability of extraction companies to remotely access products which have been purchased by police officers. This access is not only for product updates but analytics. Cellebrite, a company whose UFED device is popular with police forces around the world, including in the UK, state in their Privacy Policy that:

“When you use our Products such as the UFED Cloud Analyzer, then subject to your separate and explicit consent, we will collect information about how you use the Product under the license Cellebrite gives you, such as the number of extractions you perform with the software, which type of data source you extract, any errors you came across using the Product, the number of events you collect, how often you use the Web crawler and which views you use... All of the above data is referred to as Analytical Information.”

Cellebrite and presumably other companies can remotely access their devices which are located in UK police stations and thus access tools which are connected to the phones of victims, witnesses and suspects. This area clearly needs further interrogation. At the very least we might want to know more about the extent of this access and what safeguards are in place.

In addition, given that thousands of phones are plugged directly into these tools, the kiosks themselves are vulnerable to attack - for example they could be hijacked to send out malicious updates or a phone intentionally infected with malware could be provided for extraction, thus potentially enabling access to police infrastructure. This may not be an obvious or the simplest route for such an attack, but a determined adversary may try all means necessary. Even a nation state who is interested in a police investigation, such as that of the Skripals.

Not only do police forces need to be aware of technical security factors. As opined by Professor of Security Engineering at Cambridge University, Ross Anderson:

“Security engineering is about ensuring that systems are predictably dependable in the face of all sorts of malice, from bombers to botnets. And as attacks shift from the hard technology to the people who operate it, system must also be resilient to error, mischance and even coercion.So a realistic understanding of human stakeholders - both staff and customers - is critical; human, institutional and economic factors are already as important as technical ones."

Where next?

As more of our lives are lived online, often mediated via our phones, personal data has become increasingly valuable. The value of the data is exactly why the police want to collect, access and mine it, and criminals want to steal it.

A search of a person’s phone is far more invasive than a search of their home, not only for the quantity and detail of information but also the historical and intimate nature. The state should not have unfettered access to the totality of someone’s life and the use of mobile phone extraction requires the strictest of protections.

But, even if obtained lawfully, no data can be completely secure. Once we store data it becomes vulnerable to a breach due to accident, carelessness, insider threat, or a hostile opponent. Poor practices in handling the data, including ignorance of the way data was obtained, can undermine the prosecution of serious crimes, as well as result in the loss of files containing intimate details of people who were never charged.

It appears that in the context of mobile phone extraction, technical standards are in desperate need to ensure trust in the deployment of these powerful technologies.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Marshall, Angus.M, Paige, R, Requirements in digital forensics method definition: Observations from a UK Study, Digital Investigation 27(2018) 23-29, 20 September 2018

New Features (April 2017) Magnet Forensics [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.magnetforensics.com/blog/introducing-magnet-ai-putting-machine-learning-work-forensics/[Accessed on 23 March 2019]

Privacy Statement (2019) Cellebrite [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.cellebrite.com/fr/privacy-statement/[Accessed on 12 April 2019]

Anderson, R, Security Engineering, Indiana, Wiley, Second Edition 2008, p.889-890

NCSC (September 2018) National Cyber Security Centre [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/collection/protecting-bulk-personal-data[Accessed on: 18 March 2019]

Pidd, H, May 2017, The Guardian [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/may/04/greater-manchester-police-fined-victim-interviews-lost-in-post[Accessed on 21 April 2019]

BBC (June 2018) BBC [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-gloucestershire-44486535[Accessed on 23 March 2019]

Schneier, Bruce Beyond Fear. Thinking sensibly about security in an uncertain worldUnited States, Copernicus Books, 2006, p.11

Bowcott, O (May 2018) The Guardian [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/law/2018/may/15/police-mishandling-digital-evidence-forensic-experts-warn[Accessed on 26 April 2019]

Reiber, L, Mobile Forensic Investigations, A Guide to Evidence Collection, Analysis, and Presentation, New York, McGraw Hill, 2019, p.2

Dr Jan Collie (27 November 2018) Evidence to Select Committee on Science and Technology Available at: http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/science-and-technology-committee-lords/forensic-science/oral/93059.html[Accessed on 5 March 2019]

Marshall,A (September 2018) Science and Technology Committee, UK Parliament [ONLINE] Available at: [Accessed on 26 April 2019] http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/science-and-technology-committee-lords/forensic-science/written/89341.html

Marshall, Angus.M, Paige, R, Requirements in digital forensics method definition: Observations from a UK Study, Digital Investigation 27(2018) 23-29, 20 September 2018

Marshall, Angus.M, Paige, R, Requirements in digital forensics method definition: Observations from a UK Study, Digital Investigation 27(2018) 23-29, 20 September 2018

BBC News (October 2018) BBC Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-43315636[Accessed on 6 May 2019]

New Features (April 2017) Magnet Forensics [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.magnetforensics.com/blog/introducing-magnet-ai-putting-machine-learning-work-forensics/[Accessed on 23 March 2019]

MOBILedit News (October 2018) MobilEdit [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.mobiledit.com/news[Accessed on 01 April 2019]