How the police can access your digital communications at a protest

The police can access your digital communications. Learn how to limit the risk.

Explainer

Post date

5th May 2021

Key points

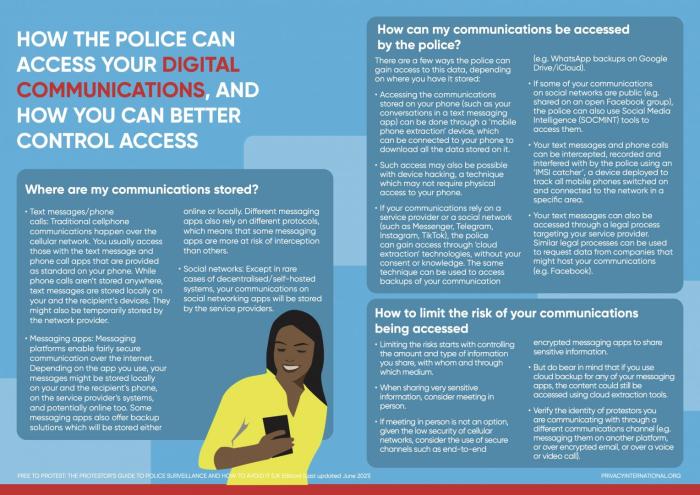

- Your digital communications are stored across a variety of locations, including on locally on your device, on a service provider’s systems or by your network provider.

- The police can gain access to your data through mobile phone extraction, device hacking, cloud extraction or social media intelligence.

- Limiting the risk of your data sharing starts by controlling the amount and type of information you share.

Where are my communications stored?

- Text messages/phone calls: Traditional cellphone communications happen over the cellular network. You usually access those with the text message and phone call apps that are provided as standard on your phone. While phone calls aren’t stored anywhere, text messages are stored locally on your and the recipient’s devices. They might also be temporarily stored by the network provider.

- Messaging apps: Messaging platforms enable fairly secure communication over the internet. Depending on the app you use, your messages might be stored locally on your and the recipient’s phone, on the service provider’s systems, and potentially online too. Some messaging apps also offer backup solutions which will be stored either online or locally. Different messaging apps also rely on different protocols, which means that some messaging apps are more at risk of interception than others.

- Social networks: Except in rare cases of decentralised/self-hosted systems, your communications on social networking apps will be stored by the service providers.

How can my communications be accessed by the police?

There are a few ways the police can gain access to this data, depending on where you have it stored:

- Accessing the communications stored on your phone (such as your conversations in a text messaging app) can be done through a ‘mobile phone extraction’ device, which can be connected to your phone to download all the data stored on it.

- Such access may also be possible with device hacking, a technique which may not require physical access to your phone.

- If your communications rely on a service provider or a social network (such as Messenger, Telegram, Instagram, TikTok), the police can gain access through ‘cloud extraction’ technologies, without your consent or knowledge. The same technique can be used to access backups of your communication (e.g: WhatsApp backups on Google Drive/iCloud).

- If some of your communications on social networks are public (e.g. shared on an open Facebook group), the police can also use Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT) tools to access them.

- Your text messages and phone calls can be intercepted, recorded and interfered with by the police using an ‘IMSI catcher’, a device deployed to track all mobile phones switched on and connected to the network in a specific area.

- Your text messages can also be accessed through a legal process targeting your service provider. Similar legal processes can be used to request data from companies that might host your communications (e.g.: Facebook).

How to limit the risk of your communications being accessed

- Limiting the risks starts with controlling the amount and type of information you share, with whom and through which medium.

- When sharing very sensitive information, consider meeting in person.

- If meeting in person is not an option, given the low security of cellular networks, consider the use of secure channels such as end-to-end encrypted messaging apps to share sensitive information.

- But do bear in mind that if you use cloud backup for any of your messaging apps, the content could still be accessed using cloud extraction tools.

- Verify the identity of protestors you are communicating with through a different communications channel (e.g. messaging them on another platform, or over encrypted email, or over a voice or video call).

You can download this guide as a jpeg by saving the image below, or by downloading the pdf version in ‘Attachments’.

Our campaign

Learn more

Target Profile