Compliant or complicit? Thai Government made American industry complicit in speech prosecution

Written by Eva Blum-Dumontet

A recent case of lèse-majesté in Thailand (speaking ill of the monarchy) is a worrying example of how Western companies do not just work with governments that fall short of international human rights standards, but can actually facilitate abuses of human rights.

Our investigation on the trial of Katha Pachachirayapong — accused of spreading rumours on the ill-health of the King Bhumibol Adulyadej, thereby causing sharp falls in the Thai stock market — reveal the obscure practices used by the secret services to investigate people suspected of criminal activity under Thai law. These laws and the investigation of the case pose threats to both the right to privacy and right to free expression. While Katha was convicted under the Computer Crime Act, there is concern that the Act is being used as a proxy for the notorious ‘lèse-majesté’.

The case reveals two worrying aspects of criminal investigations in Thailand. First, the Thai Government’s prosecution of Katha Pachachirayapong was premised on a flawed understanding of Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, identifiers assigned to devices that connect to the internet. Second, an investigation by Privacy International into the trial has revealed the problematic role played by Microsoft in this case, which provided key documentation for the appeal of this case in March 2014.

Only three core documents were shown in court to accuse Katha of being the person that the Government claimed spoke ill of the monarchy. One of those documents was a letter from Microsoft — obtained by Privacy International — revealing IP addresses related to the email account that was tied to the publication of the offending statements.

In August 2015, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights published a statement announcing they were “appalled” by the disproportionate lèse-majesté sentences that have been handed down since the May 2014 military coup. Concerns remain that lèse-majesté is used in Thailand as a way to repress opponents of those in power. It is deeply worrying that Microsoft provided evidence used to prosecute someone under laws that have been heavily criticised by international human rights organisations and other governments at the United Nations.

According to the prosecution, in 2009 Katha Pachachirayapong, a Thai stock broker, posted messages on the online forum of Fah Deaw Kan (www.sameskybooks.com) using the username Wet Dream. In these posts, the author made comments about the King’s health, claiming he was terminally ill. According to the Ministry of ICT — the complainant in this case — the messages caused a drop in the stock market.

Katha was charged under the Computer Crime Act — a law that bans internet users from posting any ‘false information’ online. Due to the vague term ‘false information’, the Computer Crime Act has been used in other cases of lèse-majesté-like statements, to prosecute almost any comment about the Royal Family perceived as negative. Katha was sentenced to two years and eight months in jail after an appeal in March 2014. He is appealing this decision. Katha has been denied bail and has remained imprisoned for the past year.

Katha has always insisted upon his innocence, stating that he was not the person behind the handle Wet Dream. Alarmingly, the evidence upon which the prosecution made its case was based on a flawed technical understanding, and the information obtained from a secret investigation by the security services in Thailand, the details of which were never revealed at trial.

The prosecution’s case relied on three pieces of evidence:

- A secret investigation by the Thai National Intelligence Agency and National Security Council asserted — based on confidential intelligence — that the email address [email protected] was tied to the Wet Dream account.

- A letter from the Krung Thai Bank stating that Katha was the owner of the [email protected] email account.

- A letter from Microsoft revealing the IP addresses from which the account [email protected] was accessed. One of the IP addresses was linked to Katha’s office.

The Microsoft letter was key to the prosecution’s case in convicting Katha. All the letter had done was to state the IP addresses from which [email protected] was accessed. According to the intelligence services’ investigation, the IP address matched Katha’s office’s. An IP address would not constitute a proof of identity as it is not permanently attributed to a device and the same IP can be attributed to more than one device. Yet the prosecution used the letter for precisely that purpose of identification. Further, the device itself can in theory be used by anyone, especially as Katha’s office computer was not password protected. The document from Microsoft was used to counter Katha’s argument that someone other than he could have used the stamp816 email address to access the Wet Dream account.

There are also concerns about how the email address linked to the Wet Dream account was obtained in the first place. Mr. Aree Jiworarak, a representative of the Ministry of ICT said in court that the investigation had not only proved the ties between the Wet Dream account and the email address [email protected] but also identified Mr. Katha as the owner of the email account. The ownership of the account was then confirmed by the letter from Krung Thai Bank.

No written report from that investigation conducted by intelligence agencies was ever provided, nor did any representatives from either agency come to the trial to testify. In a country where authorities have been threatening — before and after the military coup in May 2014 — to implement sophisticated surveillance capabilities, and where the presence of surveillance companies like Blue Coat — which provide deep packet inspection to analyse internet traffic — and spyware manufacturer Hacking Team have been documented, the lack of clarity in the process of obtaining evidence to be used in a trial is a concerning interference with the right to privacy particularly where it leads to criminal prosecution.

Considering the problematic nature of such a trial, it is alarming to see international companies like Microsoft being involved. It is essential for users to have clarification from companies like Microsoft as to when and how they share information with authorities in cases such as this, and how much they know of the nature of the criminal investigations under which the information is requested.

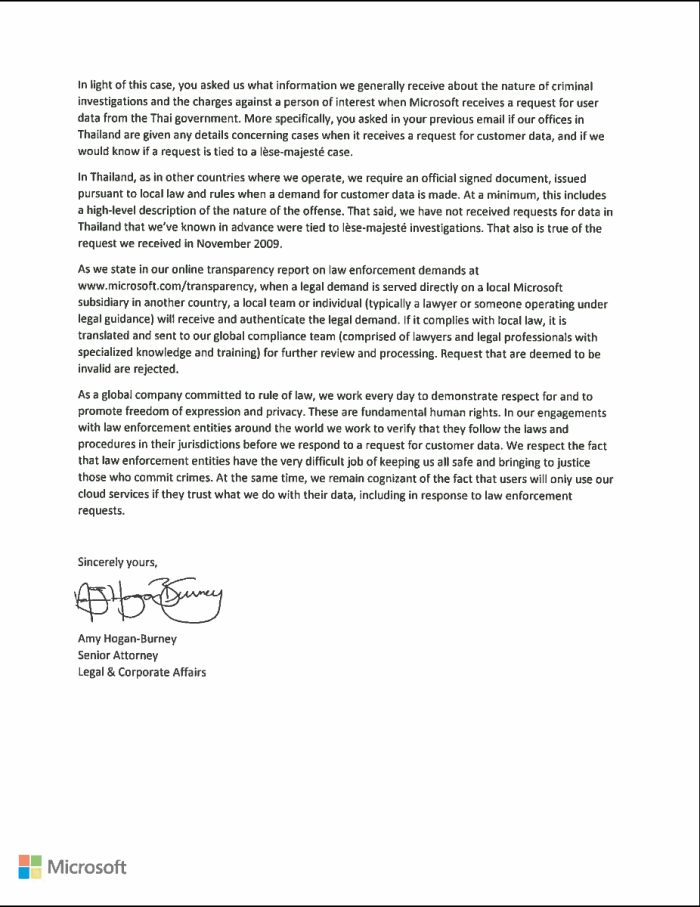

In December 2014 Privacy International contacted Microsoft Thailand to ask if they were provided with any details about the particular legal cases when they are requested to hand over customer data. In particular, we asked whether charges related to lèse-majesté would be included in the request for assistance. After having asked Privacy International to instead send out a fax with this request for information, no answer was ever provided. We then approached Microsoft headquarters in the US for an answer. Despite several exchanges of emails and repeated requests from December 2014 to February 2015, once again no answer was forthcoming.

Last week, we provided Microsoft an opportunity to respond to our investigation. They complied. Their response is posted here. In their response to us, they claim that they only respond to targeted requests under a valid legal order. The legal order was under Thai law, and was targeted at a specific user. According to Microsoft, their legal office was under the understanding that they were assisting an investigation of an email account alleged to have been used to violate Thai law by distributing erroneous information that negatively impacted Thailand’s stock exchange.

Often it is presumed that lawful requests across borders are seeking investigations of terrorists or serious organised criminals. Microsoft handed over sensitive user information to an undemocratic government thinking it was helping the investigation of ‘erroneous information’ that affected the stock market, but in fact was aiding a prosecution into free expression.

So now the key emerging question is: what should a company do to interrogate the nature of the requests they are receiving? We would question whether Microsoft should have even cooperated with the ‘lawful’ request of investigating the dissemination of ‘erroneous information’ — and it is well understood by most that Microsoft certainly should never assist in the prosecution of a free speech offence. But they did comply.

The U.S. internet industry has various approaches to Thailand. In their 2014 transparency report, Google revealed that they had rejected every request for user data from the Thai government. In contrast, Microsoft’s transparency report revealed they had provided data for 89 per cent of requests over the first half of 2014. The transparency report for the second half of 2014 reported that Microsoft rejected 30 per cent of requests, compared to less than two per cent over the first six months (over ten per cent of the data requested were not found).

It is clear that the Thai government is determined to engage with large Western internet companies. Last December, the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (the telecommunication regulatory body) invited representatives of Facebook to discuss the issue of lèse-majesté and ask them to assist the Government in cracking down on individuals accused of speaking ill of the monarchy. Facebook reportedly declined the invitation, claiming no representatives were available.

The role of private companies in protecting their users’ right to privacy, whether service providers or social media platforms, is only going to grow as they expand further into different regions and come up against different legal frameworks. Where called upon to provide information under laws routinely criticised around the world and by international organisations for their detrimental effect on fundamental human rights such as privacy and freedom of speech, Privacy International urges these companies to resist these demands from the Thai military Government and to develop clear rules for how and when they cooperate with governments, democratic or not.