The Steady Drip Of The Erosion Of The Right To Privacy

1984: A broad law, a broad power and a whole lot of secrecy

In the wake of litigation brought by Privacy International (‘PI’) and as the Government prepared to introduce the Draft Investigatory Powers Bill (‘IP Bill’) in November 2015, there was a cascade of ‘avowals’- admissions that the intelligence agencies carry out some highly intrusive surveillance operations under powers contained in outdated and confusing legislation.

It is disappointing that it has been almost six months since the Draft Investigatory Powers Bill was published, with a purported aim of improving transparency the Agencies are still in the process of fessing up.

This begs the question, what more aren’t you telling us?

Recent Admissions

Recently, we have learned more about how GCHQ and MI5 have used section 94 of the 1984 Telecommunications Act to collect our data in bulk.

These admissions were made in the course of PI’s case in the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) about the Agencies’ (MI5, MI6, GCHQ) use of section 94 of the 1984 Telecommunications Act. The hearing is set for the week commencing 25 July 2016.

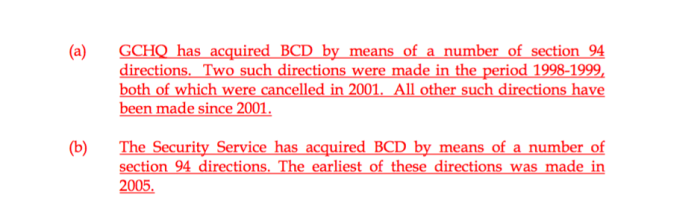

In paragraph 196 of the Government Amended Response to the Privacy International’s (the Applicant) Grounds, it is admitted:

196

(a) GCHQ has acquired Bulk Communications Data (BCD) by means of a number of section 94 directions. Two such directions were made in the period 1998 – 1999, both of which were cancelled in 2001. All other such directions have been made since 2001.

(b) The Security Service has acquired BCD by means of a number of section 94 directions. The earliest of these directions was made in 2005.

To those who have not followed these revelations closely, this might not look significant. But make no mistake, this is huge. This is 19 years of using a power in total secret, without even the Intelligence and Security Committee, the Parliamentary body that is meant to oversee all of the surveillance agencies’ capabilities, having any knowledge of the use of BCDs, or that Section 94(1) was being (ab)used.

The Intelligence Agencies continue to rely on section 94(1) and ‘directions given by the Secretary of State’ to the current day. These directions are general, surrounded by secrecy, not time bound and not reviewed independently. They have been used by the intelligence agencies to collect Communications Data outside Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 (RIPA) powers, unhindered by the Home Office’s Statutory Code of Practice on Communications Data Acquisition.

We do not know how many section 94 directions have been made, how many have been cancelled, what data is stored, what it is used for and if the data is ever deleted.

The only previous admission on the extent of use was on 4 November 2015, when the Home Secretary revealed that after the September 11attacks MI5 was authorised to start collecting data on which telephone numbers called each other and when in bulk, under a section 94 direction instead of RIPA – the latter would have brought independent oversight and regulation, the former allowed them to do so without any oversight whatsoever.

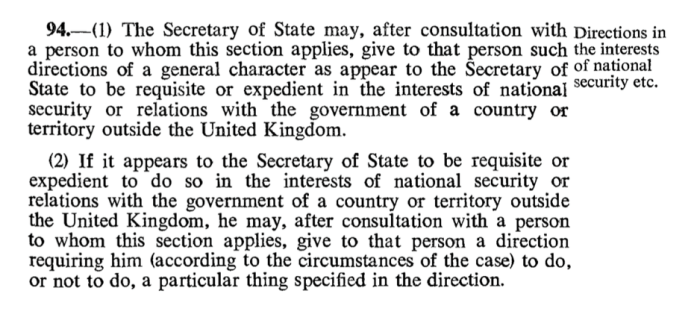

The 1984 Telecommunications Act

The original focus of the Telecommunications Act was to privatise British Telecom (BT), establish Oftel as telecommunications regulator, and introduce a licensing system, develop new modem standards and criminalise indecent phone calls. However, tucked away in the ‘Miscellaneous’ provisions of the Act, section 94 provides a very broad power to any Secretary of State (Home Office, Transport, Health, Culture, and so on) to give secret directions to any provider of a public electronic communications network. Communications providers can be instructed ‘to do, or not to do’ any thing specified and the direction does not automatically expire.

Was the use of Section 94 to collect communications data in bulk known by Parliament?

The Government Response to our litigation contains a number of worrying statements. Paragraph 200 states:

At all material times the powers conferred by section 94 included a power to require CSPs to provide BCD. The principles of legality does not arise; given the statutory context, the use of the power in this way was plainly within the contemplation of Parliament.

Unless Parliament was making a bizarre homage to George Orwell, it is hard to see that the way section 94 was used some 14 years later, could have in anyway been contemplated by Parliament. The Amberhawk blog pointed out that in 1984 there were few networked computers, thus there could have been no Parliamentary discussions about communications data collection in terms of the Internet or modern day networked computers.

Former MP Julian Huppert, writing in August 2015, noted that the ‘astonishingly broad power’ of clause 94 was ‘So well tucked away (in the miscellaneous provisions) that it was never even debated in Parliament.’ He stated that he spent considerable time as an MP pushing on this, trying to find out how often these extraordinary powers were used, and who was checking they were being used appropriately. He got nowhere, with the then security Minister James Brokenshire saying:

“If the question relates to section 94 of the Telecommunications Act, then I am afraid I can neither confirm nor deny any issues in relation to the utilisation or otherwise of section 94”.

At the same Home Affairs Select Committee session, where this statement was made by Brokenshire, BT refused to deny it had handed over data to the Intelligence Agencies.

It is also notable, as stated in the Amberhawk blog that section 94 was updated in a very minor way by paragraph 70 of Schedule 17 (“Minor and Consequential Amendments”) of the Telecommunications Act 2003; for instance replacement of the words “requisite or expedient” by the word “necessary” in Section 94. So there was an opportunity to provide a full explanation to Parliament of the intended impact of Section 94 at this point, but was not taken by the then Home Secretary David Blunkett.

It was not until November 2015 that use of section 94 to require telecommunications companies to provide bulk access to communications data outside the protections of the RIPA regime (Gordon Corera Intercept: The Secret History of Computers and Spies (2105) p.332), was avowed.

Has this power been used for hacking or intercept of content?

It was always believed that section 94 was only used to obtain communications data. However, a confusing paragraph in the amended response to our legal challenge states:

198. For the avoidance of doubt, no directions have ever been made under section 94 authorising the obtaining of the content of communications and/or the carrying out of equipment or property interference. The Respondents contend that such conduct can only be lawfully undertaken when authorised under the relevant provisions of (respectively) RIPA 2011, ISA 1994 and Part III of the Police Act 1997. For completeness the Respondents do contend that directions under section 94 can lawfully be made to require CSPs to facilitate conduct that has already been made lawful by authorisations under the aforesaid provisions.

Is section 94 being used to install code in Apps? Create backdoors to encrypted services for authorities? Enable requisitioning of databases?

This paragraph may further indicate that section 94 previously played the role that the controversial Technical Capability Notices (clause 217)and National Security Notices (Clause 216, 281-200) would play in the IP Bill. These powers, as with section 94, are squirreled away in the Miscellaneous chapter of the ‘Miscellaneous’ Provisions labelled ‘Additional powers’. Not only do they make fresh provision for the Secretary of State to issue national security notices in secret to telecommunications providers in secret, there is concern that they will be used to undermine encryption, and could be used to compel telecommunications providers to assist the agencies in vaguely defined and sweeping operations, including hacking. There is no meaningful judicial authorisation process.

We have written in more detail about Technical Capability & National Security Notices here and here.

Safeguards and Oversight

Not only has the use of the power been far from transparent, there has and is, given that this power is still in operation, no meaningful or effective oversight regime: no statutory review by the Commissioner; no provision for a review of directions; no Code of Practice; no judicial authorisation; and the directions do not expire. David Anderson QC in A Question of Trust said:

6.17 ... s94... is very broad in nature and imposes no limit on the kinds of direction that may be given. There is nothing in the public domain concerning the use of that power and the exercise of the s94 power is not subject to any oversight or external supervision.

13.31 ... Obscure laws – and there are few more impenetrable than RIPA and its satellites – corrode democracy itself, because neither the public to whom they apply, nor even the legislators who debate and amend them, fully understand what they mean. Thus... TA 1984 s94... are so baldly stated as to tell the citizen little about how they are liable to be used.

Sir Mark Waller confirmed to Mr Huppert in 2014 at the Home Affairs Select Committee that:

“there is not statutory oversight of that section.”

The Interception of Communications Commissioner, asked in 2015 by Prime Minister David Cameron to oversee section 94 directions, pointed to the lack of a central record, which raises concern about the ability to carry out effective oversight in any event:

“there does not appear to be a comprehensive central record of the directions that have been issued by the various Secretaries of State”.

The Response confirms there has been no independent external oversight of the ongoing need for the directions:

197.

(d) The ongoing need for each of the directions has been subject to review both within the Security Service and GCHQ and also be the Home Secretary and Foreign Secretary.

Despite there being a requirement that the Secretary of State lay a copy of every direction before Parliament, to alert Parliament to any misuse, no section 94 direction has ever been laid before Parliament. All have been kept secret. Presumably, this secrecy derives from section 94(5) that excuses the need for scrutiny if it would be against the interests of national security or relations with foreign governments or the commercial interests of any person. The exception has apparently been allowed to perpetually override the rule.

To quote Julian Huppert again, ‘if the US asked us to make BT install some spyware or to hand over user data, no one can be told about it if that would upset either the US or BT.’

Conclusion

For the past year the Intelligence Agencies have been congratulated on coming clean. These recent revelations show that there is potential that many activities and legal regimes remain in the shadows. Far from congratulating them we need them to reveal what else they’ve not been telling us.

Note

Communications Data is anything that is not the content of the communication such as origin, destination, route, time, date, size, duration etc. Privacy International’s Grounds were re-amended following the admissions regarding section 94 of the 1984 Act.