State of Surveillance in the Philippines

This guest piece was written by Jessamine Pacis of the Foundation for Media Alternatives. It does not necessarily reflect the views or position of Privacy International.

Introduction

With a history immersed in years of colonialism and tainted by martial law, Philippine society is no stranger to surveillance. Even now, tales of past regimes tracking their citizens’ every move find their way into people’s everyday conversations. This, for the most part, has kept Filipinos vigilant over their hard-earned right to privacy and freedom of expression.

However, it is difficult to gauge how much this level of awareness has influenced the population’s view of the slew of surveillance incidents that have occurred in recent years.

The Philippines has emerged, and is steadily retaining its place, as one of the biggest users of mobile and internet in Southeast Asia. In this era of increased connectivity, policies and regulating bodies on communication technologies are becoming more critical, as demonstrated by very recent developments such as the long-delayed creation of the National Privacy Commission.

The Past

Several prominent cases have directed the spotlight towards the prevalence of communications surveillance in the country. The most controversial incident to date remains the “Hello Garci” scandal, in which a wiretapped conversation between former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and an election commissioner exposed what appeared to be an electoral fraud scheme favoring Arroyo during the 2004 presidential elections. Other notable incidents include a leaked recorded conversation between former President Corazon Aquino and two Cabinet members regarding the impact of the then-new Constitution on U.S. military bases in the country.

The Present

The current internet penetration rate and use in the Philippines is remarkably high, especially considering the country’s dismal internet speed. One global study also ranked the country as being first in daily internet use (in terms of number of hours spent online), with an average of 6.3 hours of computer use per day and 3.3 hours per day if mobile device owners(the global median is 2.7 hours). Social media use is also popular, with the country taking credit for 30 million Facebook accounts in 2013. Such high levels of usage are puzzling given the country’s average internet connection speed of 2.5 Mbps compared tothe global rate, which is 4.5 Mbps.

The Philippine legal framework generally frowns upon communication surveillance. Although the term has yet to be defined under domestic law, few would contest the fact that it is proscribed or restricted. This view proceeds mainly from the Constitutional guarantee of “the privacy of communication and correspondence,” and the number of international conventions on privacy and human rights the country subscribes to, namely: the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Communications surveillance is also considered a felony or crime in certain cases, as can be gleaned from the following statutes: the Revised Penal Code, the Electronics Engineering Law of 2004, and the Anti-Wiretapping Act of 1965. Nevertheless, other laws sanction the activity as a legitimate law enforcement measure for specific purposes, such as in the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2012, the Human Security Act of 2007, and the Anti-Child Pornography Act of 2009.

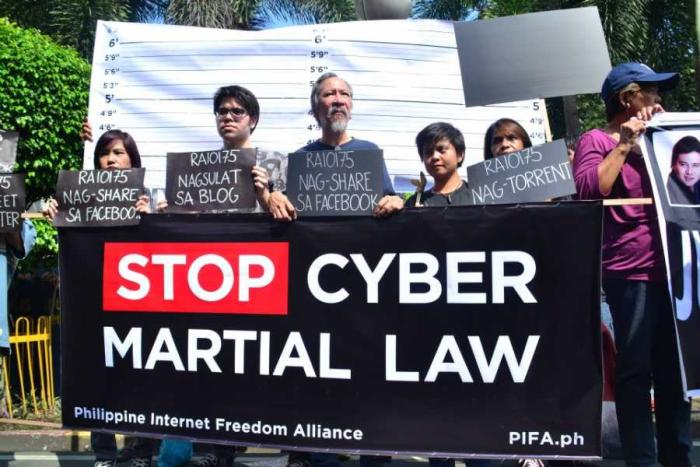

At present, the two most important statutes concerning digital privacy and surveillance are the Cybercrime Prevention Act (CPA) of 2012 (RA 10175) and the Data Privacy Act (DPA) of 2012 (RA 10173). Regarding the former, it is worth noting that although the Supreme Court has already struck down a provision that would have allowed law enforcement authorities to collect or record traffic data through electronic means in real-time without the need for judicial authorisation, the law still allows the interception of communications and the disclosure and preservation of computer data in specific conditions. RA 10173, on the other hand, provides possible legal remedies against communication surveillance. It establishes the general rule that the processing of privileged information is a prohibited activity, subject to certain exceptions.

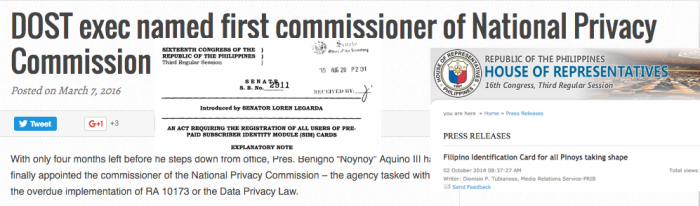

However, while the CPA and the DPA have laid the groundwork for a comprehensive legal regime on privacy, implementation is taking longer to fully take off. In fact, although both laws were enacted in 2012, the implementing rules and regulations for the CPA were published only in 2015, whereas the National Privacy Commission, tasked to implement the rules for the DPA were appointed only in March 2016.

The Future

Numerous reports suggest that the Philippine government has acquired, or has been planning to acquire, various surveillance technologies, which include: (1) PISCES, a US government-developed biometric identification technology used for border control; (2) IMSI catchers, or phone monitoring kits that provide active intercept capabilities; (3) Galileo Remote Control System, an intrusion malware tool; and (4) Signal, a New Zealand-manufactured software for large-scale social media analysis. The Philippine government’s interaction with its U.S. counterpart is particularly significant, considering that the latter has constantly been accused of engaging in surveillance activities within the country’s borders. In early 2015, for instance, a downed US military surveillance drone was discovered in the Quezon province. Documents leaked by former US National Security Agency (NSA) contractor Edward Snowden in May 2014 also revealed that the NSA “had access via DSD asset in a Philippine provider site” and “collects Philippine GSM, short message service (SMS), and Call Detail Records.”

There is some degree of consolation in a recent development. In March 2016, almost four years after the DPA mandated the creation of the National Privacy Commission (NPC), the first NPC commissioner and deputy commissioners were finally appointed. The NPC is tasked to develop the implementing rules and regulations of the DPA—a massive undertaking that could dictate the future of privacy and surveillance in the Philippines. Given the breakneck speed with which new technologies are developed, the Commission needs to take into account not only the issues and mechanisms that are currently in place, but also those proposed measures that might eventually affect the people’s right to privacy. Chief among these are the persistent attempts to require the registration of SIM cards and establish a national identification system. Both policy proposals involve the acquisition and use of sensitive information such as biometric data.

With all the privacy-related issues that confront the Philippines and the rest of the world today, the NPC is certain to have their hands full. Should they do their mandates justice, they may very well set the proper tone for the country’s approach to privacy in the decades to come.