Aerostats, Biometrics, Chips, and Drones: UK Gathers Surveillance Industry to Solve Brexit Border Question

Image: Eric Jones

The UK government last week hosted hundreds of surveillance companies as it continues to try and identify “technology-based solutions” able to reconcile the need for controls at the Irish border with the need to avoid them.

The annual showcase conference of 'Security and Policing' brings together some of the most advanced security equipment with government agencies from around the world. It is off limits to the public and media.

This year’s event came as EU and UK Brexit negotiators finally begin to outline concrete proposals regarding how the 310-mile Irish – UK border will look once the UK leaves the EU. At stake is not only the terms of the UK’s withdrawal, but avoiding a return to violence in the island of Ireland and UK mainland – something largely avoided since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which among other provisions guaranteed an open border.

While both the EU and UK have agreed that there will be no return to a "hard border", and the UK Government has said it will be "frictionless", how this will be achieved remains a mystery. Although sorting out customs arrangements is the main issue, border security – policing the movement of people and goods – is also a central question.

If a technological solution to this does exist, it will have been on show at Security and Policing, described by the UK government as “the corner-stone of the security calendar” and “the premier platform for relevant UK suppliers to showcase the very latest equipment”.

The Verdict?

Unfortunately, simply throwing technology at complex political issues rarely resolves them; and in this case it is apparent that even if the most bombastic marketing claims were taken at face value, none of the tech on show would lead to a truly frictionless border while satisfying the UK's Brexit "red-lines".

Any solution would require physical infrastructure, waiting time, or be so intrusive that it would be illegal.

And even if such a solution could be found, it ignores the broader political point: surveillance technologies are technologies of control, and political control is exactly what the Northern Ireland conflict was all about. Physical surveillance infrastructure, no matter how small, and security checkpoints, no matter how efficient, are still symbolic of control, difference, and division - exactly the opposite of what an open border represents.

Likely, a combination of hi-tech gadgets could be deployed to effectively monitor everyone and everything passing through the border, but at the expense of making it one of the most surveilled and militarised borders in the world; exactly what needs to be avoided. So with that in mind, compiled below is our take on some of the most relevant technologies on show.

Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR)

The use of ANPR on the border is a near certainty. ANPR cameras can capture vehicles’ registrations to be then transferred to various databases owned by and retained for various periods – their excessive use is something which PI has successfully challenged. ANPR can be used for a range of applications, including parking and speed enforcement, but also to track the movement of vehicles, for example as they approach and go through a border. Jenoptik’s ANPR tech for example can be used to analyse “white list / black list vehicles, non-return, overstay and prohibited …journey time analysis, speed, flow, stay time and many more reports.”

RFID

Radiofrequency Identification involves the storage of digital data stored in tags which can then be read by a scanner through radio waves. This makes them particularly useful for tracking and authenticating objects in which they’re embedded, which can be anything from passports to potatoes. For border security, they can be used as chips in ID documents which when scanned will retrieve information from relevant databases. They’re regularly used for these purposes on the US – Canada border.

At Security and Policing was UK company TC SENS, makers of RFID tech specifically marketed for electronic toll collection, vehicle identification, and border crossings.

The use of both ANPR and RFID was suggested by a European Parliamentary report on prospects for the border post Brexit, but as anyone who's driven past ANPR cameras knows, they are physical infrastructure, and the use of RFID at borders still requires waiting - it would not be frictionless.

Visual surveillance

Visual surveillance used to monitor the border is about a lot more than just CCTV. Advanced persistent aerial surveillance systems developed for military use on drones, aerostats, or planes are being used to monitor entire cities from the skies, capturing detailed video images and transferring them to ground stations for analysis. The UK Ministry of Defence has already bought several ‘pseudo-satellites’ from defence contractor and exhibitor Airbus, which claims they are able to hover over a location from several miles for a period of weeks or months collecting detailed footage. Search Systems Ltd last week demonstrated their wide area surveillance system – supported by the UK Border Force – which is mounted onto an aerostat.

Other companies included Sesanti, whose LREO Advanced Long-Range Imaging System offers thermal imaging and claims to be able to identify vehicles in excess of 30km and people beyond a distance of 8km, and can be equipped with analysis tools such as identifying vessels through their AIS signal.

Qinetiq, formerly part of the UK government, sells cameras using “advanced passive millimetre wave” technology to detect hidden items such as weapons on people in crowds; the SPO-NX system has already been trailed in cooperation with the UK Home Office at an entertainment venue where it scanned up to 1000 people per hour.

All of these systems require visible large physical infrastructure or systems designed for military use in combat settings.

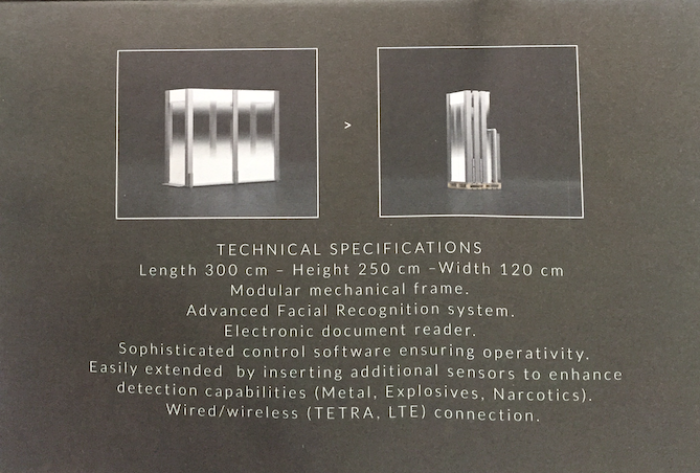

Image from a brochure by Qinetiq

Biometrics

The use of biometrics - the identification and authentication of people based on physiological or behavioural measurements - is increasingly widespread in everyday life and the market for its use by government is set to rocket. Beyond having a fingerprint or face authenticated by your own devices, their use is quickly growing for cybersecurity, law enforcement, access control and even for providing access to public services. The use of “on the move” biometrics technology – the acquisition of biometric data from a distance - is the next big aspiration of governments, promising more data collection and less waiting time, for example at borders. To be clear, the dream of 'at a distance' biometrics means taking your biometrics without your involvement, or likely without your knowledge.

It is therefore a massive threat, potentially meaning that soon biometric verification will be required for everything, with huge amounts of resulting data being used for analysis, inferences, and blacklisting by various companies and authorities.

It’s not a solution to the border issue because it still requires physical infrastructure, is still inaccurate, and is still slow - it will not make the border “frictionless”. Singapore’s attempts to use the latest on the move technology for border crossings demonstrated at a showcase organised by the EU’s border agency still involves significant waiting times; no other technology currently on offer - iris, facial, fingerprint, or voice - would stop the need for significant delays.

At display at Security and Policing was Italian arms manufacturer Leonardo, which sells on the move facial recognition technology boasting the use of using artificial intelligence techniques for analysis, multinational NEC’s NeoFace Watch, which captures facial images from a distance and similarly claims artificial intelligence techniques, UK-based Tensor and Iproov, and Unisys, which in addition to making biometrics is also the maker of LineSight, an analysis platform using algorithms and machine learning to predict the “intent” of travellers – sorting them into low and high risk profiles.

Image from a brochure marketing Leonardo's platform for real-time automated identity control, featuring biometric and thermal cameras

Perimeter detection

Qinetiq also demonstrated their Optasense Border Security and Surveillance system, a set of fiber optic cables laid into the ground which act as sensors for changes in acoustics, stress, pressure and temperature. The sensors would then be able to detect personnel or vehicles in an area and locate them – for example crossing a border - and can monitor a length of 5000 km from one location, more than ten times the length of the UK-Ireland border. Future Fibre Technologies sell similar fibre optic intrusion detection and location systems.

Cell Site Analysis & IMSI Catchers

When your phone connects to a network, it does so through cell towers: these cell towers in turn hold a lot of data about which devices connected to it and when. By requesting or obtaining this data from the operator of a tower, it is possible for an authority to identify which cell tower(s) a device connected to, and its location.

If an authority doesn't have a target number, they are able to obtain data on all the devices which connected to a cell tower during a specific period. These so-called ‘cell tower dumps’ are known to be used by law enforcement in the US (Verizon received nearly 9000 court orders for them in the first half of 2017) but the power is not publicly avowed in the UK, and there is little information about how the power is used. Create Intelligence, a UK company producing software used for data analytics “deployed in some of the largest law enforcement agencies in the UK”, advertises solutions for analysing cell tower dumps.

If authorities don’t want to have to go to a telecommunications operator to get data from cell towers through a legal process, they instead make their own cell towers and trick devices to connect to them. These fake cell towers known as IMSI catchers can then be used to identify and track devices, intercept messages and calls, and send messages to a device. They can be used for example at a protest to identify participants, or at borders to identify devices in the area, but they would still have to be mounted onto a tower, in a vehicle or on a drone or aircraft.

While the UK government maintains that the new legal framework governing surveillance in the UK provides “unparalleled openness and transparency”, the very existence of IMSI catchers is ‘neither confirmed nor denied’ by all UK authorities, despite the fact that the UK government approves the export of hundreds of them, and numerous companies are demonstrated them last week at Security and Policing.

UK company Smith Myers launched 'Airborne-NESIE', capable of geolocating and identifying mobiles from drones or aircraft “Perfect for airborne operations such as interdiction, trafficking, border security”; Switzerland-based NeoSoft, whose attempts to sell an IMSI catcher to a Bangladeshi unit described as a ‘death squad’ were stopped after intervention by Privacy International, WOZ, and Swiss export authorities; Canada-based Exfo demonstrated their IMSI catchers capable of intercepting messages, calls, and decryption; as did UK companies DNA-Tracker, GOS Systems, Seven Technologies Group (formerly Datong), Cellxion, and Gamma International.

Image of an IMSI catcher from a brochure marketed by Exfo

Mass Surveillance

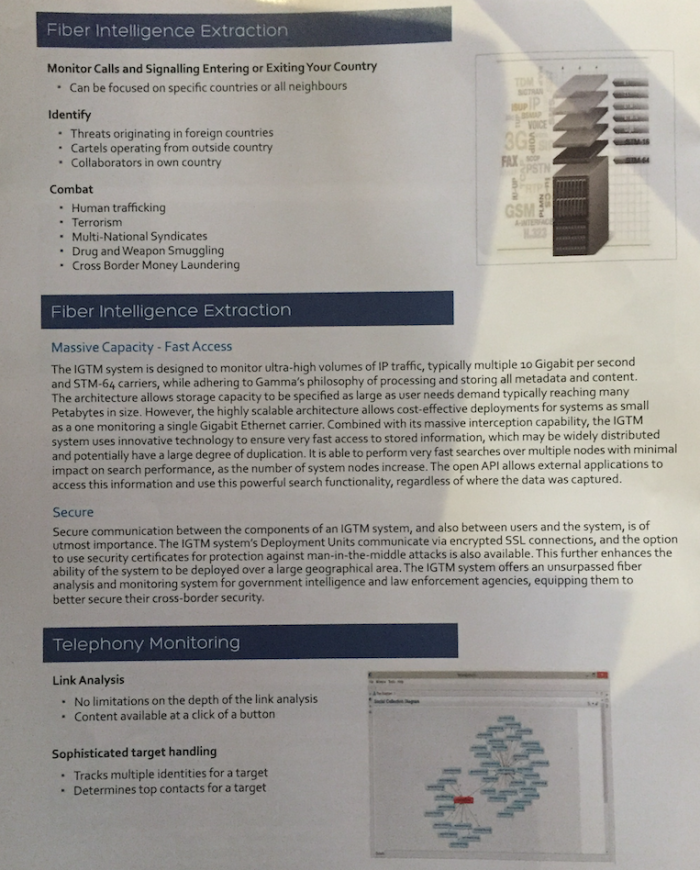

Mass untargeted surveillance empowers intelligence agencies with the ability to spy on anyone using the internet or a phone, using the data to make detailed observations and inferences not only to try and investigate crime, but to predict it. In addition to spying on the data of citizens held in domestic networks, the global nature of how internet traffic travels across fibre cables and between international servers also gives agencies vast access to foreigners’ traffic, without the legal safeguards reserved for nationals. UK and Irish authorities both engage in mass surveillance for border security and other purposes.

While it can be used to effectively build detailed intelligence on people, it requires that they actually use a phone or the internet. It is also massively illegal; the UK's chief Brexit negotiator David Davis even brought an ultimately successful case against such indiscriminate surveillance powers at the European Court of Justice.

UK company GOS Systems offers “mass interception” surveillance products, as does UK’s largest arms company BAE Systems, which was last year reported to have exported mass internet surveillance systems to numerous Arab countries where human rights abuses at the hands of intelligence agencies are common.

UK company Gamma International also markets mass internet surveillance capabilities for cross-border security deployed on international gateways in fiber optic networks, which “can be focused on specific countries or all neighbours”, allowing the identification of threats and cartels “operating from outside country” as well as “collaborators in own country”.

Netherlands-based Group 2000 launched launched at Security and Policing a new mass internet surveillance product, the LIMA IP Mass Metadata Monitor, “designed to analyse IP traffic for very large input bandwidth” and carry out pattern identification.

US company JSI market an “IP Recorder” which uses Deep Packet Inspection to collect internet traffic and can intercept “thousands of IP targets simultaneously” to extract metadata and content.

JSI also markets a “mass intelligence analysis” system for phone surveillance, allowing “country-wide collection” designed to collect “hundreds of millions of mobile and landline phone records per day” and retain them for in-depth analysis: “this mass gathering and long-term retention allows you to visualise trends, behaviours, and the patterns people repeat, helping you to forecast the future”.