Why Do We Still Accept That Governments Collect And Snoop On Our Data?

This piece was written by Ashley Gorski, who is an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union, and PI legal officer Scarlet Kim and originally appeared in The Guardian here.

In recent weeks, the Hollywood film about Edward Snowden and the movement to pardon the NSA whistleblower have renewed worldwide attention on the scope and substance of government surveillance programs. In the United States, however, the debate has often been a narrow one, focused on the rights of Americans under domestic law but mostly blind to the privacy rights of millions of others affected by this surveillance.

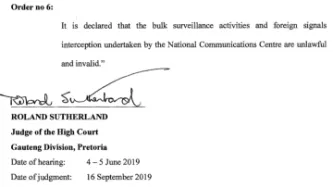

Indeed, just last week, a British court held that British intelligence agencies acted unlawfully by concealing bulk spying programs from the public for over a decade. Soon, in a lawsuit brought by Privacy International, the ACLU and eight other organizations, the influential European court of human rights will also weigh in on surveillance programs revealed by Snowden, and the result could have implications far beyond Europe.

Although the debate in the US has led to some piecemeal reforms — including the USA Freedom Act and modest policy changes — many of the most intrusive government surveillance programs remain largely intact. These include programs conducted not just by the NSA, but also by its close partner in the United Kingdom, called the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), with whom the NSA swaps vast sets of private data.

This bulk surveillance violates rights to privacy and freedom of expression — rights that are guaranteed not only under US domestic law, but also under international human rights law. That latter legal framework speaks a universal language, enumerating fundamental rights that every person enjoys by virtue of our common humanity.

Following the Snowden revelations, we brought suit in British court, challenging surveillance programs that violate these fundamental rights. The case has now made its way to the European court of human rights, where we recently filed our principal submission. The court plays a critical role in the international human rights system by enforcing the European Convention on Human Rights, a treaty ratified by 47 nations. Its judgments are legally binding and its rulings help shape the interpretation of human rights law throughout the world.

The lawsuit challenges the British government’s mass surveillance of internet traffic transiting undersea fiber-optic cables, as well as the UK’s access to information gathered through the NSA’s breathtaking array of bulk spyingprograms. These have included, for example, the NSA’s recording of every single cellphone call into, out of, and within at least two countries; its collection of hundreds of millions of contact lists and address books from personal email and instant-messaging accounts; and its surreptitious interception of data from Google and Yahoo user accounts as that information travels between those companies’ data centers located abroad. The suit also seeks to shed light on the secret information-sharing agreements governing GCHQ’s access to these massive hoards of NSA-collected data — and vice versa.

While this lawsuit has clear implications for the rights of non-Americans, it matters for Americans as well. It is one of the first direct challenges to mass surveillance within the international human rights framework. The judgments of the European court of human rights influence the interpretation of other international human rights instruments, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which the US ratified in 1992. A determination by the court that GCHQ’s mass surveillance is unlawful would call comparable NSA surveillance programs into question by sending a powerful message that they are fundamentally incompatible with human rights.

The international human rights law framework makes clear that government surveillance must be prescribed by law, targeted and proportionate. These requirements are designed to balance a government’s need to address security threats and its obligation to protect fundamental rights. Bulk spying programs plainly fail that test.

By their very nature, bulk spying programs are neither targeted nor proportionate. They invade the privacy of broad swaths of people without any individualized suspicion of wrongdoing. Surveillance should be directed at obtaining specific intelligence in individual operations, not indiscriminately subjecting all of our private information to government scrutiny.

Moreover, in both the UK and US, the legal basis for and full scope of government surveillance powers remain opaque. Critical safeguards — such as independent judicial review of spying programs — are hobbled or, in many instances, non-existent.

The intelligence-sharing arrangements challenged in this case underscore a critically important fact as well: we are all foreigners to someone. The British government’s mass surveillance programs surely intercept the communications and data of Americans. If Americans are concerned about other countries intercepting their information in bulk and sharing that information — including with the US government — then they should care about ensuring there is an international legal framework that constrains these activities.

Just as human rights law requires that surveillance be prescribed by law, targeted, and proportionate, government information-sharing should adhere to the same standard. Outsourcing surveillance hardly lessens the intrusion. Therefore, whether the UK or US intercepts the information itself or obtains the same flow of data from another intelligence agency, the same protections should apply.

As the debate over mass surveillance continues, it is vital that we consider the ways in which this spying violates the fundamental rights of millions of individuals throughout the world. Should the European court of human rights rule against mass surveillance, its decision will have far-reaching implications for the rights of Americans and non-Americans alike.