An Open Source Guide to Researching Surveillance Transfers

Privacy International’s new report shows how countries with powerful security agencies are training, equipping, and directly financing foreign surveillance agencies. Driven by advances in technology, increased surveillance is both powered by and empowering rising authoritarianism globally, as well as attacks on democracy, peoples’ rights, and the rule of law.

To ensure that surveillance powers used by governments are used to protect rather than endanger people, it is essential that the public, activists, journalists, and oversight bodies first know what these powers are. One of the main ways of doing this is by overseeing what capabilities they have access to – and how foreign governments and surveillance companies are empowering them.

Privacy International has written this guide to highlight some of the open-source data sources available in the English language which can be used in research and investigations.

Training & Funding

Training and funding of foreign security forces is done by international institutions, law enforcement, military, and intelligence agencies, as well as by development, justice, and foreign departments. Getting data therefore depends on the body concerned. Many of these provide general information on some of these programmes which can also be used to inform further research.

United States

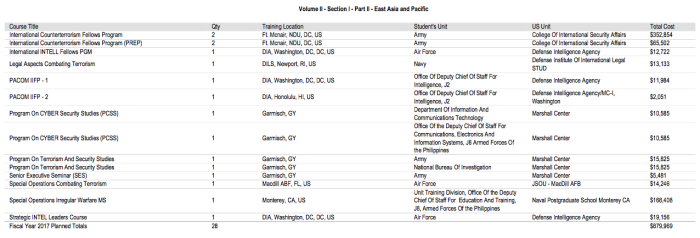

In the US, the State (DoS) and Defense (DoD) Departments submit joint annual reports to congress describing ‘security assistance’ provided to foreign agencies. These are available here, and contain a breakdown of the country and agency concerned. For example, if you were looking to see what training has been provided to a certain country and in what area, you can look through these annual reports, which describe in general the type of training being provided, by which US body, and to which agency.

US government training courses provided to agencies in the Philippines

Security Assistance Monitor, a US-based research project, has collated this data and regularly provides expert analyses and data, which can be found here. Security Assistance Monitor also provides a guide on how to use the data, and how to access the raw data provided by US agencies on which it is based.

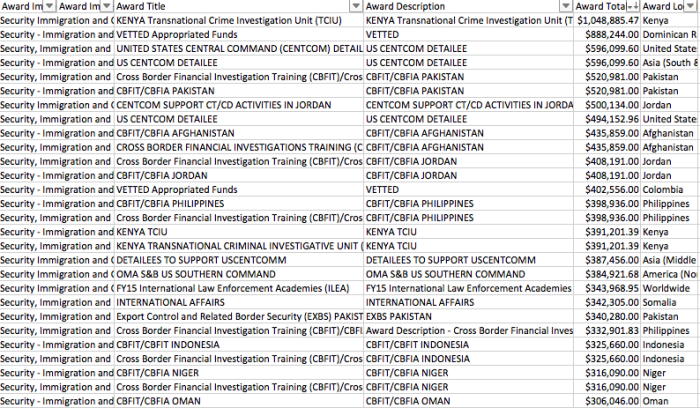

Other DoD information relating to policy and budgets can be found on its Open Government portal; budget documents describe general details of what some funds are used for. For example the Counterterrorism Partnership Fund is used to finance foreign agencies fighting Boko Haram, including Cameroon’s security forces, which have recently been accused by Amnesty of carrying out severe human rights abuses, including the use torture, as well as war crimes as part of their fight against the armed group.

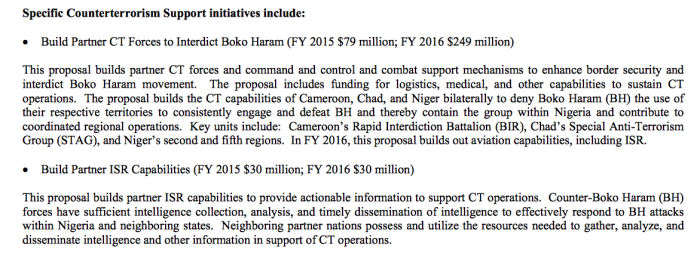

Some US agencies engaged in financing and training foreign security agencies also provide data to the US aid transparency portal, foreignassistance.gov. This includes the Departments of Defense, State, Interior, Justice, and Homeland Security. For example, it’s possible to get a breakdown of appropriated funds for specific agencies, projects, and countries – such as DoD Train & Equip programmes around the world, or the work which Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), does with other security agencies around the world.

Training provided by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)

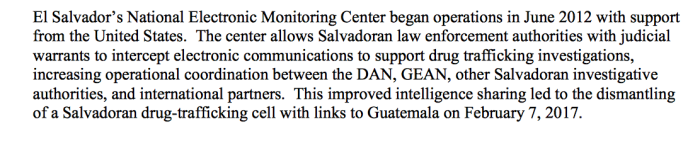

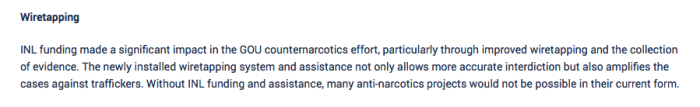

Specific US agencies and programmes sometimes provide their own publicly-available audit reports. For example, US Department of State Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) works with foreign security agencies with the mandate of reducing “the amount of crime and illegal drugs reaching U.S. shores.” The agency produces annual reports detailing US counter-narcotics strategy, which outlines trends and US facilitation of capabilities abroad, as well (up until 2009) as end-use monitoring reports, which for example shows INL funding for telecommunications wiretapping in Uruguay.

Description from US INL end-use monitoring report

No publicly-available information is available covering the work done by intelligence agencies such as the US National Security Agency, which is known to work with foreign spy agencies, for example funding and training the surveillance agency in Ethiopia.

Europe

European countries and European Union (EU) institutions provide various data on surveillance training and funding activities.

The EU, through various funds, instruments, and agencies, provides substantial support to non-EU countries, particularly those close to the EU border with governments willing to implement border control measures. Information about the various projects are available across the webpages of the various EU institutions.

Frontex, the EU’s border control agency, has formal working arrangements with authorities in 18 countries, coordinating activities and providing training in border control measures and other technical assistance.

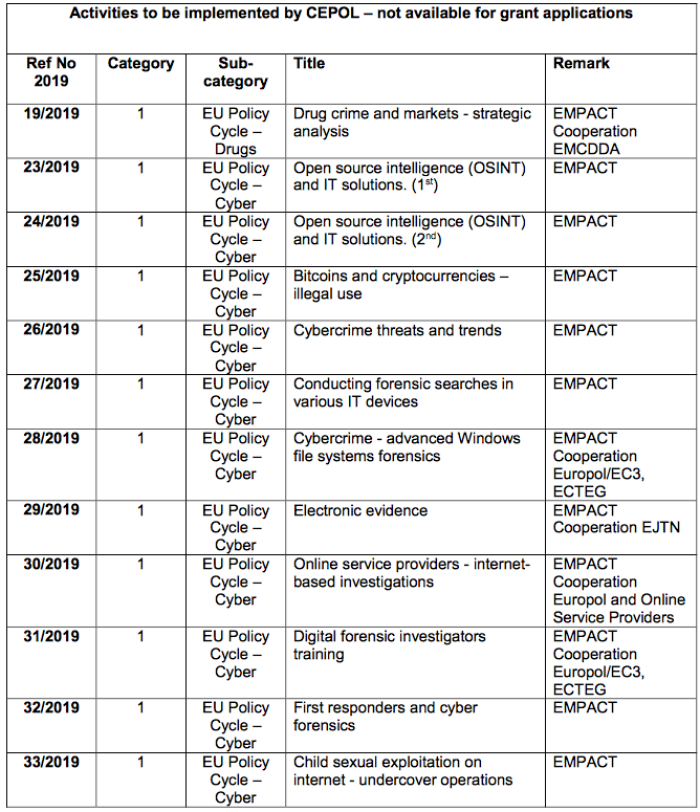

The European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training, based in Hungary, trains EU and non-EU law enforcement agencies on surveillance techniques.

Example of training courses implemented by the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Training

The European External Action Service, the EU’s foreign policy body, manages various funds; the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa for example, with an allocated budget of €3.3 billion, supports 26 countries to improve resilience to food insecurity, support job creation, and address human rights abuses. A key focus of the fund is migration, for example committing €28 million to develop Senegal’s nationwide biometric system (implemented by a private security company formerly part of the French Ministry of Interior). The projects are available under the various thematic and regional webpages.

Information about the funding of Senegal’s nationwide biometric system

The European Commission, the EU’s executive body, has multiple departments which work with countries abroad. The EU’s Financial Transparency System provides searchable information on all the beneficiaries of funds awarded by the Commission through its departments, its staff in the EU delegations, or through executive agencies.

Information available on The EU’s Financial Transparency System

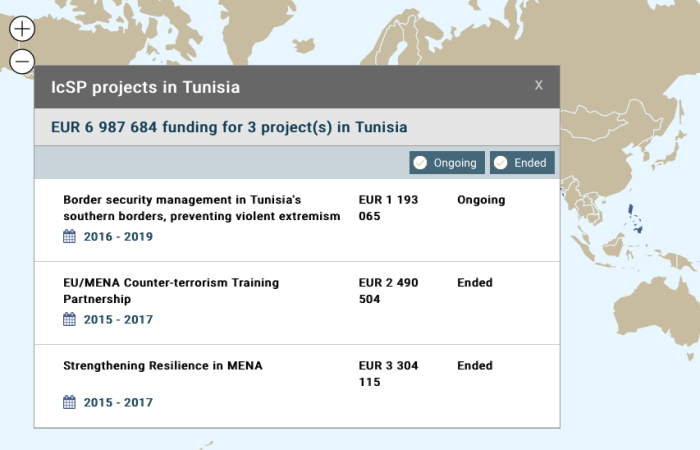

The Foreign Policy Instruments department implements projects aimed at, for example, empowering women, mine clearance, and electoral monitoring, as well as the Instrument contributing to Stability & Peace (IcSP) which funds conflict prevention and peace-building projects, some of which facilitate surveillance and border controls in foreign countries. A map detailing the projects is available here.

IcSP projects in Tunisia

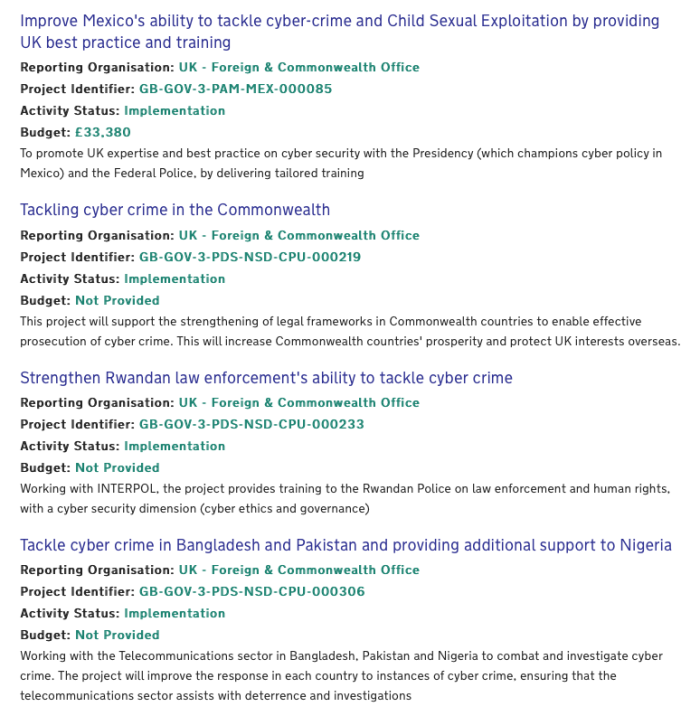

Individual EU countries also publish general information about security cooperation with foreign countries, most commonly on aid transparency platforms. The UK’s Conflict, Stabilisation and Security Fund (CSSF), for example, worth £1 billion funds projects in over 40 countries, including the training of police and armed forces in foreign countries, for example training Jordan’s “internal security agencies to use investigative [counter-terrorism] policing tools”. A general description of some of the projects is available on the UK government website. A joint parliamentary committee recently concluded that the level of secrecy of how the fund operates meant that it could not “provide parliamentary accountability for taxpayers’ money spent via the CSSF.”

Information about projects financed by the CSSF

Transfers of Surveillance Equipment

Surveillance equipment used by government agencies is produced by hundreds of companies around the world largely based in large arms-exporting states with the biggest spy agencies. Privacy International together with Transparency Toolkit have collected information on 528 surveillance companies as part of the Surveillance Industry Index (SII), which includes information on the companies’ locations, products, and sales, and is available at sii.transparencytoolkit.org. A report summarising this industry is available here.

Obtaining information about sales and exports is difficult due to excessive national security and corporate secrecy, and relies on investigative research techniques, freedom of information requests, leaks, and whistle-blowers. SII is designed to help researchers obtain information by providing company information; using this makes it possible to conduct further research, by for example submitting freedom of information requests. General information however can also be found within government transparency reporting.

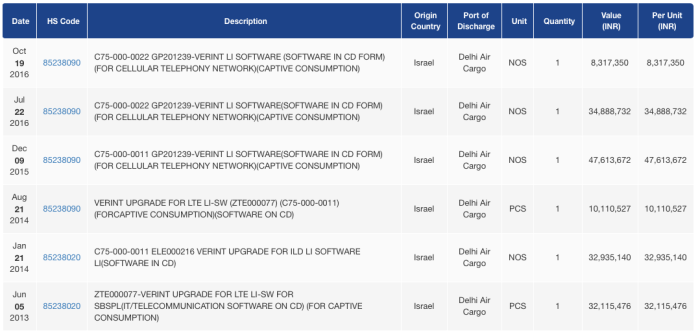

For example, some countries, for example India, publish shipping data about imports and exports. Searching for surveillance company names (available in the SII) in this data, or for industry terms commonly used by the surveillance industry, it’s possible to finds imports of surveillance equipment.

Shipping import data to India, available on multiple sites (this example from here)

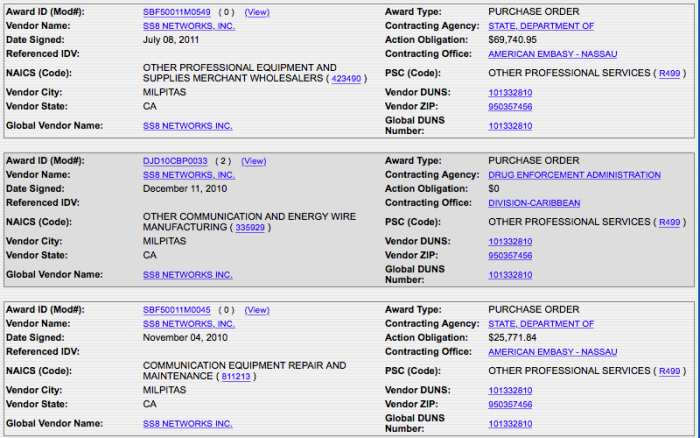

Government procurement data is one of the best open sources for finding information about sales. Centralised government procurement sites are available in addition to tender documentation on agencies’ dedicated websites, though in-depth details are often restricted. Companies, products, and capabilities to search can be found in SII: for example, searching for specific surveillance companies or types of equipment will sometimes retrieve relevant data.

US federal procurement site, showing contracts between SS8, a surveillance company providing interception of telecommunications networks, and the US embassy in the Bahamas.

By searching for specific companies or government departments on the site, it is possible to find information on US government contracts.

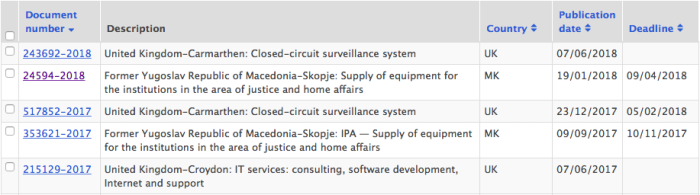

Similarly, the EU publishes procurement data on its site TED, for example this search shows EU contracts for facial recognition technology.

Procurement data from TED matching a search for facial recognition

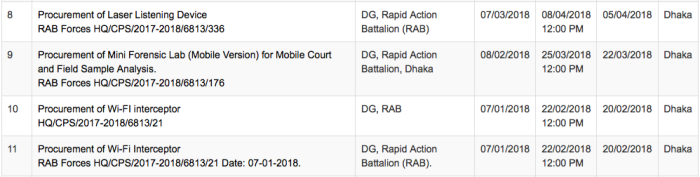

Individual countries also make publicly available procurement data, such as the Bangladeshi national procurement site, here showing various tender notices for various surveillance equipment.

Tender notices for the Bangladeshi Rapid Action Battalion, a notorious security agency dubbed a ‘death squad’ for its part in abuses

Export control data

If a company wants to export equipment which the government wants to possibly stop or monitor, most large-arms exporting states have an export control system in place which puts a legal obligation on companies to seek prior government permission before exporting an item.

Governments generally decide which items need to be controlled through international mechanisms, for example the Wassenaar Arrangement in which participating countries decide which military and “dual use” items should be controlled. There are several surveillance items which are currently on the list, which means that participating states also control their export. Each item has a code on the list, which countries also use in their own national control lists; the list is publicly available, and a list of the most relevant categories is below in the Annex.

Some of these countries then report publicly on which licenses they have approved or denied, which means that data about which exports companies have sought licenses for is available. This data therefore provides details about surveillance exports; depending on how much data is provided, it can provide information on the company, the product, how much an export is worth, and the end-user of the product.

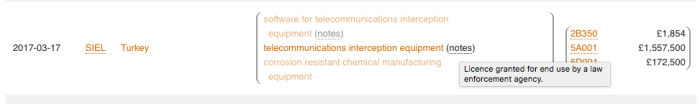

Switzerland, for example, publishes data every quarter on the webpage of the export control agency, though stops short at providing information on the company or the end-user within a country. The United Kingdom also publishes data every quarter on a dedicated platform, which is however specialised and complicated to interpret. The Campaign Against the Arms Trade has developed a resource which simplifies this, which is publicly available on their site. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute has a list of all the countries which make public information about exports, available on their site.

UK export licensing data showing the approval of a license to a law enforcement agency in Turkey

Other data comes from ad-hoc parliamentary reviews; for example, Germany undertook a review in 2015 providing information about exports from Germany of all the categories which could be interpreted to be useful for surveillance.

Most countries, including countries where a lot of surveillance companies are based such as France, Germany, Israel, Italy, and Sweden, do not however provide information in sufficient detail to be able to understand what type of equipment is being exported. They either provide no data at all (even in the EU which generally has more transparency measures around exports of military and dual use equipment, 11 out of the 28 member states 11 refused to provide any details when asked by journalists), or authorities only provide general statistical data.

Using freedom of information requests however, journalists have been successful in obtaining information about exports.

- Motherboard, for example, has been successful in obtaining a list of companies which have applied for export licenses to the UK export authorities and has mapped exports from the UK.

- SpyTechExports has obtained data about exports of surreptitious listening devices from the United States, the UK and elsewhere.

- The BBC and Information Dagbladet, have been able to obtain copies of export license documentation from Denmark, confirming the role BAE Systems has played in selling internet surveillance equipment to authoritarian countries around the world.

- Computer Weekly has also been able to obtain internal UK government correspondence, showing how different government departments assess license applications, and confirming the lack of a suitable risk analysis when the UK signed-off on a license to export an IMSI Catcher to an agency in Macedonia subsequently responsible for the mass wiretapping of 20,000 activists, politicians, and journalists.

- Telerama has been able to obtain data about a French surveillance company selling mass internet surveillance equipment across the Middle East and North Africa.

- The Finnish government provided detailed information about exports of telecommunications interception equipment in response to a freedom of information request by Privacy International.

Obtaining information through such requests is difficult however, and dependent on the restrictive policies of the agency concerned. Intelligence agencies, which directly equip counterparts in foreign countries, are in some countries such as the UK completely exempt from any freedom of information legislation.

Instead of relying on such disclosures, Privacy International and other NGOs around the world have been calling for the EU to pass binding legislation which will make transparency reporting about surveillance exports mandatory across the EU – it is hoped this will be passed before the next European Parliamentary elections in 2019. Depending on how far EU legislators are prepared to go, it could mean that information about surveillance exporters, products, and end-users will be regularly made publicly available.

It’s important that these reforms pass; not only is such transparency important to providing information on the surveillance industry and trade, as well as being essential to tackling corruption, it is also a democratic necessity: these decisions are being taken on the basis of government policy. If oversight bodies, parliament, and the public don’t know what these decisions are, they have no way of knowing if policy is being followed, let alone if the policy itself is the democratic will of the people.

While authoritarian governments continue to operate in secrecy, and as more democratic governments continue to use over-broad definitions of national security and prioritise corporate secrecy, it is down to researchers around the world to find and expose surveillance transfers. Failing to track how governments are being equipped with powers and the companies making millions facilitating them will only see surveillance being used against peoples’ rights, to further authoritarianism, and to undermine democracy.

If you have any questions or sources of information, please email [email protected].

Annex: Surveillance items currently within international export control lists

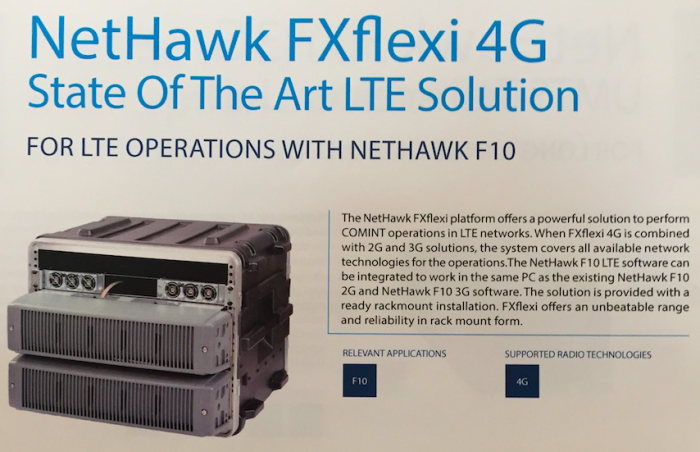

“5.A.1.f Mobile telecommunications interception or jamming equipment, and monitoring equipment therefor, as follows, and specially designed components therefor”

This includes items such as ‘IMSI Catchers’ which can locate, track, and intercept communications from all mobile phones in a certain area, as well as satellite phone interception equipment.

Finnish-based EXFO exports IMSI Catchers around the world, including to authoritarian countries which have targeted electronic surveillance at human rights activists,

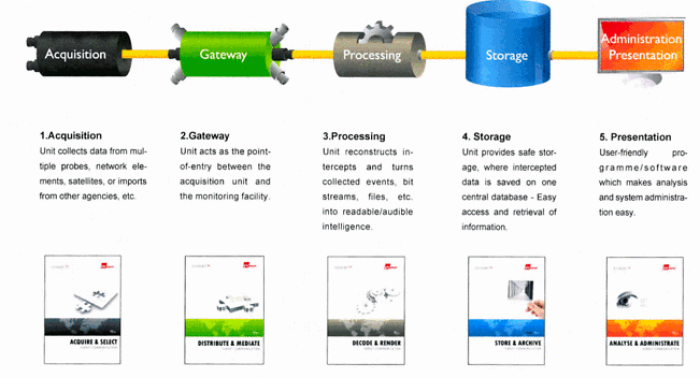

“5.A.1.j IP network communications surveillance systems or equipment, and specially designed components therefor”

This includes large scale internet monitoring tools, such as those exported to authoritarian states around the world by BAE Systems.

Evident, an internet surveillance system produced by ETI, a Danish firm acquired by BAE Systems.

“4.A.5 Systems, equipment, and components therefor, specially designed or modified for the generation, command and control, or delivery of "intrusion software"”

This can include systems used to control malware used in hacking operations for surveillance, which is capable of attacking devices to access all available data and control functions such as the camera and microphone. This category may also be used by countries to control activities crucial to protecting privacy, such as IT security research (PI and other NGOs are pressing authorities to update this category to protect IT research).

NSO Group, a $1 billion-valued surveillance company sells malware for surveillance to clients around the world, and has been used to target human rights defenders and journalists.

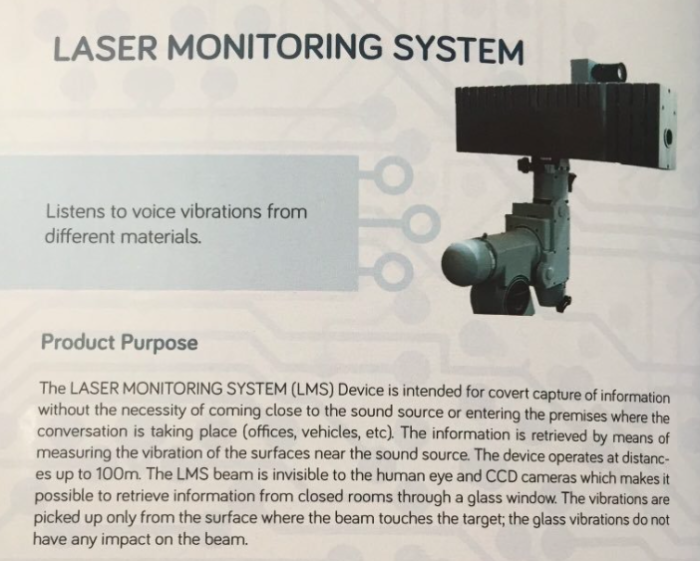

“6.A.5.G 'Laser acoustic detection equipment'”

Commonly known as a laser microphone, which can be used for example to listen to conversations through windows.

A laser microphone sold by a Lithuania-based surveillance company, Tigbis.

“5.A.2 “"Information security" systems, equipment and components, as follows…”

Countries also control the export of items which contain certain levels of cryptography. Cryptography is essential to securing data, protecting it from the likes of criminal groups, and is now even more essential as more data is generated and held by our devices as well as by companies and governments who hold information about us. Though this category has been significantly watered-down since the 90s (during what is known as the Crypto-Wars), it still controls a wide range of items, including some items which can be used for surveillance, but which aren’t listed explicitly within any other category. For example, if a company were to sell communications interception and retention systems, and were to use certain levels of cryptography which isn’t exempted from control to keep the intercepted data secure from being hacked, it would need an export license under this category.

“ML11.A Electronic systems or equipment, designed either for surveillance and monitoring of the electro-magnetic spectrum for military intelligence or security purposes or for counteracting such surveillance and monitoring”

Similar to cryptographic items, this category controls a wide range of items “specially designed for military use”, including, for example, infrared or thermal imaging monitoring equipment and military surveillance aircraft.

“9.A.12 "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles" ("UAVs"), unmanned "airships", related equipment and components, as follows”

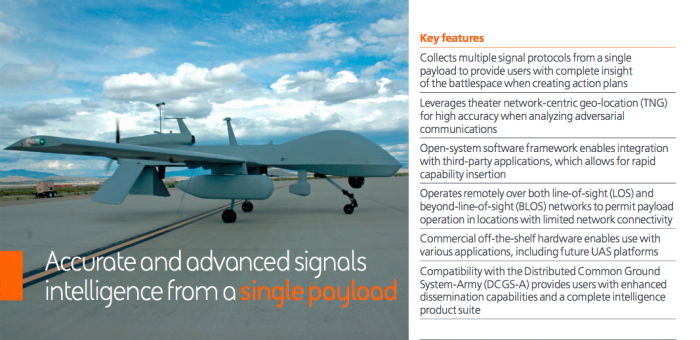

This category controls UAVs, or drones, which are designed to be able to fly out of sight of the operator and within certain performance levels. Drones can be fitted with advanced persistent aerial surveillance systems which can monitor, in detail and for hours at a time, movements on the ground, as well as electronic signals surveillance equipment which can be used to, for example, monitor mobile phone communications. Data generated by mobile phone use is used to target people for assassination by drones.

BAE Systems sells signals monitoring equipment to the US Army.