Surveillance Company Cellebrite Finds a New Exploit: Spying on Asylum Seekers

- Cellebrite, a surveillance firm marketing itself as the “global leader in digital intelligence”, is marketing its digital extraction devices at a new target: authorities interrogating people seeking asylum.

- In Bahrain, Cellebrite’s technology was reportedly used to extract conversations and data from Mohammed al-Singace, a political activist who was tortured in custody.

- European countries are increasingly using smartphone surveillance to investigate asylum seekers. Reportedly, in 2017 Germany and Denmark expanded laws enabling immigration officials to conduct such examination of people’s phones, while the UK and Norway have been carrying out the practice for years.

Cellebrite, a surveillance firm marketing itself as the “global leader in digital intelligence”, is marketing its digital extraction devices at a new target: authorities interrogating people seeking asylum.

Israel-based Cellebrite, a subsidiary of Japan’s Sun Corporation, markets forensic tools which empower authorities to bypass passwords on digital devices, allowing them to download, analyse, and visualise data.

Its products are in wide use across the world: a 2019 marketing brochure (below) claims they have more than “60,000 licenses deployed in 150 countries”; a hack of the company in 2017 revealed apparent communications with customers in Turkey, Russia, and the UAE.

The use of powerful and intrusive technology that enables authorities to gather intimate details about people’s lives carries significant dangers. Often these tools are used without adequate protections or scrutiny, and are rolled out in secret. In Bahrain, Cellebrite’s technology was reportedly used to extract conversations and data from Mohammed al-Singace, a political activist who was tortured in custody.

The potential use of its product to investigate the digital lives of people seeking asylum was outlined by its VP of International Marketing in a pitch last month in Morocco to government officials gathered from around the world.

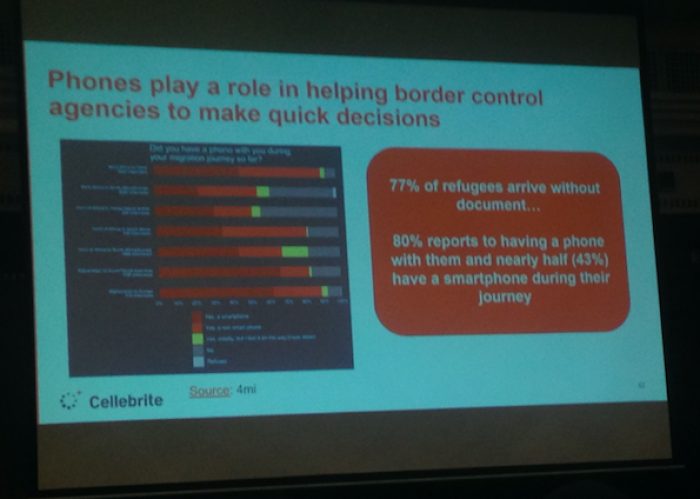

According to Cellebrite’s salesperson, some “77% of refugees [sic] arrive without document”, while 43% have a smartphone during their journey – insisting that in lieu of documents, a person’s phone could be used to find out who they are, what they have been doing, where they have been, when, and ultimately why they are seeking asylum.

Smart phones are vital for migrants – not just for keeping in touch, but because they are a key means by which they plan journeys and obtain information, including information on safe routes and potential risks such as dangerous smugglers, as well as information about accessing vital services when they arrive in a safe country.

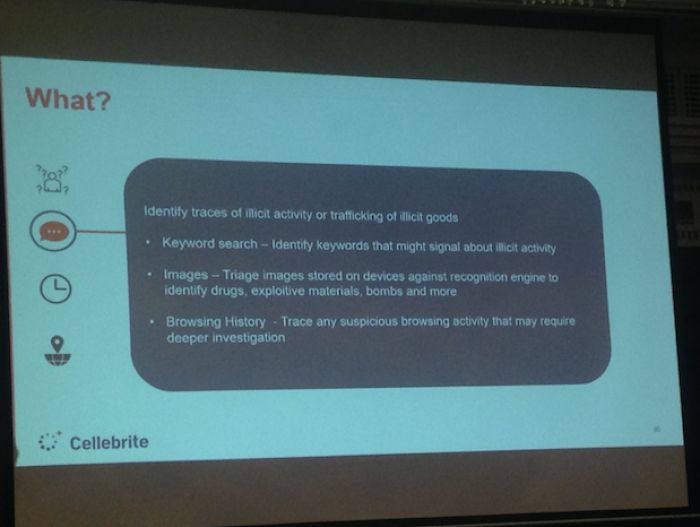

By analysing the phone, Cellebrite claims its technology can audit a “person’s journey to identify suspicious activity prior to arrival”, track their route, run a keyword and image search through their device to identify “traces of illicit activity”, and review their online browsing and social media activity.

Location tracking is performed by accessing GPS records on the device, as well as phone metadata (which could, for example, be the location information automatically associated with photos and networks to which the device has connected) and locations based on social media posts.

Once the device is accessed, the software also analyses data stored on the cloud – which typically includes back-ups of files. An analysis of Cellebrite’s software conducted by Privacy International last year found that it could retrieve data which the user would believe has deleted.

When asked how they bypass password protections on more expensive devices which have more secure access controls – such as Apple’s iOS – a technical expert working for Cellebrite confirmed to Privacy International that “we have exploits”. Exploits are highly-prized code used to take advantage of known and unknown vulnerabilities in a device’s software to hack into a system.

European countries are increasingly using smartphone surveillance to investigate asylum seekers. As reported by Wired, in 2017 Germany and Denmark expanded laws enabling immigration officials to conduct such examination of people’s phones, while the UK and Norway have been carrying out the practice for years. In Germany, more than 8000 phones were searched in half a year after passing the powers. Last year, Austria passed a similar law.

In May 2018, the UK Home Office's Immigration Enforcement authority made a payment of £45,000 to Cellebrite.

When asked by the audience in Morocco about legal frameworks governing its use, the Cellebrite salesperson remarked that new laws could either be introduced or existing ones amended to request people hand over their devices or be banned from entering, but that in any case there is usually “consent” from those seeking asylum.

Lawfullness

Whether a country has a law in place or relies on “consent”, such forensic examinations are still highly problematic.

Under international human rights law, surveillance is an interference with the right to privacy, and therefore needs to abide by numerous principles designed to safeguard against arbitrary searches which undermine democracy and people’s fundamental rights. For example, any surveillance needs to be necessary and proportionate to the overall aim, and not be discriminatory based on characteristics such as race or birth origin.

This means that national laws requiring invasive surveillance measures can still be a violation of international law if they do not meet these standards.

Forensic analyses of smart phones are highly invasive. As noted in the landmark US ruling of Riley v California, an element of pervasiveness characterises mobile phones with data that can go back years and shed light on nearly every aspect of a person’s life. The US Supreme Court ruled that whilst data on a mobile phone is not immune from search, a warrant is generally required before such a search, even in connection with an arrest.

Privacy International’s work in the UK has demonstrated that even where certain statutes are relied upon to carry out mobile phone extractions, they are often woefully inadequate, date from long before the smart phone and do not deal with the specific and unique intrusions posed by use of these technologies.

When it comes to “consent”, it is more complicated than simply acquiring a person’s permission. As articulated under European data protection regulations, for example, consent is not freely given and informed if the entity requesting it is in a position of power over the individual, or fear adverse consequences so that they are not in a position to disagree. If a person fears being denied asylum and deported if they don’t hand over their phone, it does not constitute “consent”. It can hardly be said that consent is fully informed or unequivocal if the person concerned is unlikely to have full knowledge of the scope or types of information that may be extracted and retained.

Further, the assumption that obtaining data from digital devices leads to reliable evidence is flawed. If a person claims certain information is true, and there exists information on their smartphone suggesting otherwise, it is not evidence that they are lying. They may have swapped phones, they may have accessed certain sites or liked certain social media activity for a whole variety of reasons, and they may have been in touch with people whose name spelling appears on watchlists for a whole variety of reasons. And just because a person fleeing persecution from government forces does not want an agent flicking through their photos and messages, it also doesn’t mean that they are automatically lying.

Exploitation

For all these reasons, Privacy International is continuing to monitor and challenge the increasing use of such device extractions surveillance tools around the world, including at borders.

The use of such extraction tools, which are supposed to be used in exceptional circumstances, is part of a broader trend of aiming surveillance and other security technology at asylum seekers and migrants, often on scientifically dubious grounds. In Europe, this includes the use of technology which supposedly identifies if a person is lying based on their ‘micro-gestures’, a person’s origin based on their voice, and their age based on their bones.

The interjection of for-profit actors such as surveillance companies offering easy technological solutions into this highly complex issue is inherently dangerous.

Millions of people being forced to migrate because of war, persecution, and climate change is a call for urgent political and social action, not a business opportunity.