Two states admit bulk interception practices: why does it matter?

Six years after NSA contractor Edward Snowden leaked documents providing details about how states' mass surveillance programmes function, two states – the UK and South Africa – publicly admit using bulk interception capabilities.

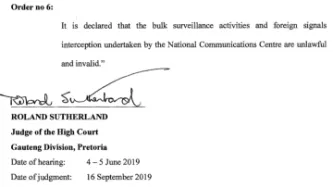

Both governments have been conducting bulk interception of internet traffic by tapping undersea fibre optic cables landing in the UK and South Africa respectively in secret for years.

Both admissions came during and as a result of legal proceedings brought by Privacy International and other civil society actors challenging – among others – these interception capabilities.

Why does it matter?

Multiple whistleblowers and journalists have been reporting about the bulk interception capabilities of the US, UK and other governments across the globe for the past decade or more. The Snowden revelations in 2013 constituted a pivotal moment in history where these allegations were backed by thousands of documents that showed in excruciating detail the mass surveillance programmes – their capabilities, functions and procedures – of some of the most powerful countries in the world.

But even after the Snowden disclosures, governments refused to acknowledge the existence of these programmes, which could potentially put each and every one of us under the microscope of state surveillance. Characteristically, immediately after the Snowden revelations British defence officials issued a confidential UK Defence-Notice (D-notice) to media groups in an attempt to censor coverage of surveillance tactics employed by intelligence agencies. It took continuous pressure and legal action by many civil society actors for these two governments to admit the existence of these bulk interception programmes.

Despite the South African intelligence agencies’ confidence that it is a generally accepted practice – they repeat that multiple times – the circumstances under which the two governments admitted using their mass surveillance capabilities indicates that they are not entirely comfortable talking about them. Their admission is buried in legal proceedings. However, the UN Human Rights Committee has already expressed concerns regarding the mass surveillance powers of both UK and South Africa.

Which cases exactly?

The United Kingdom

In the UK, the case began in 2013, following Edward Snowden’s revelations that the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) has in secret attached probes to the undersea fibre optic cables landing in the UK. Widely known as the “Tempora” programme, the government never admitted its existence.

Privacy International and nine other NGOs challenged the legality of such practices shortly after. The case has already gone through national proceedings and is now before Europe's highest human rights court – the European Court of Human Rights – for a second time. The legal complaint was originally brought before the UK Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) in July 2013. The IPT determined, among others, that the UK bulk interception regime was unlawful because the legal framework governing such access was secret. The applicants before the European Court challenge this decision and argue that the UK bulk interception violates Articles 8 and 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which respectively protect the right to privacy and the right to freedom of expression.

The Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights has been asked to revisit the Court's first ruling on our case, challenging UK mass surveillance and intelligence sharing as incompatible with Articles 8 (right to privacy) and 10 (freedom of expression) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

On 10 July 2019, the UK government admitted the existence of the programme in submissions made ahead of and during the hearing before the Grand Chamber.

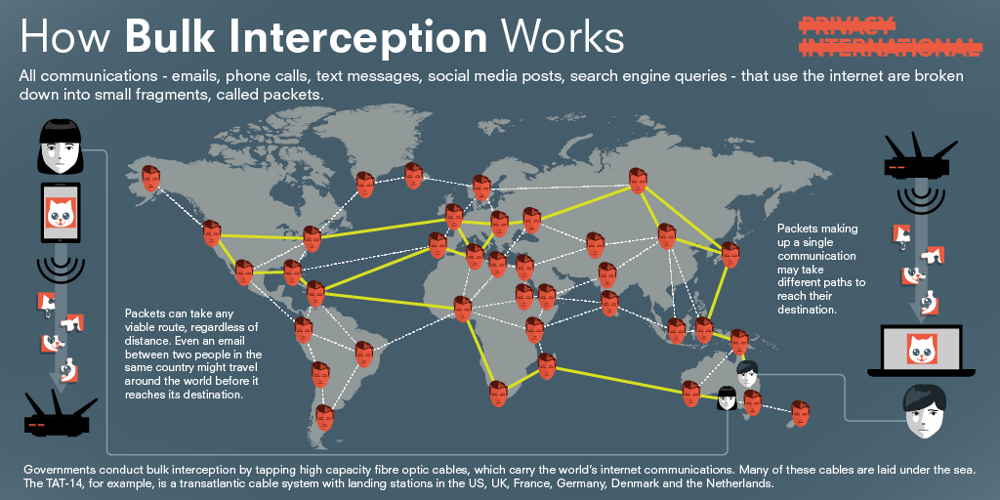

The UK government for the first time described in relative detail – compared to previous statements – the process of collection, filtering, ‘selection for examination’ and examination of communications intercepted in bulk. They describe the distinction between ‘simple’ and ‘complex’ queries, the selectors used and briefly how they operate:

- For ‘simple’ queries they allegedly use a single “strong selector”, such as a telephone number or email address.

- For ‘complex’ queries, “they combine a number of criteria, which may include weaker selectors”. For example, the ‘complex’ inquiries will search “for material which combined use of a particular language, emanation from a particular geographical region, and use of a specific technology. Other selectors used in complex queries may for example involve the use of a complex digital signature created by a particular machine used in cyber attacks, or the use of a call sign from a particular vessel.”

Apparently, ‘simple’ queries will apply against all bearers, while ‘complex’ queries will apply against a selected few bearers. The criteria for the selection of bearers are not described.

Regarding the selectors, the government added: “The choice of selectors to effect selection of communications for examination is also itself carefully controlled. (…) Selectors applied directly to bearers are subject to a rigorous process of automated rules, augmented by human intervention where necessary, to ensure that they meet the appropriate legal and policy requirements.” Selectors can be used for a maximum three month period before a review is necessary. Analysts of the material selected for examination receive training, but no further information on this is provided.

The government finally refers to the retention period. “Communications to which the “strong selector” process is applied are discarded immediately, unless they match the strong selector. Communications to which the “complex query” process is applied are retained for a few days, in order to allow the process to be carried out, and are then automatically deleted, unless they have been selected for examination.” (emphasis added)

South Africa

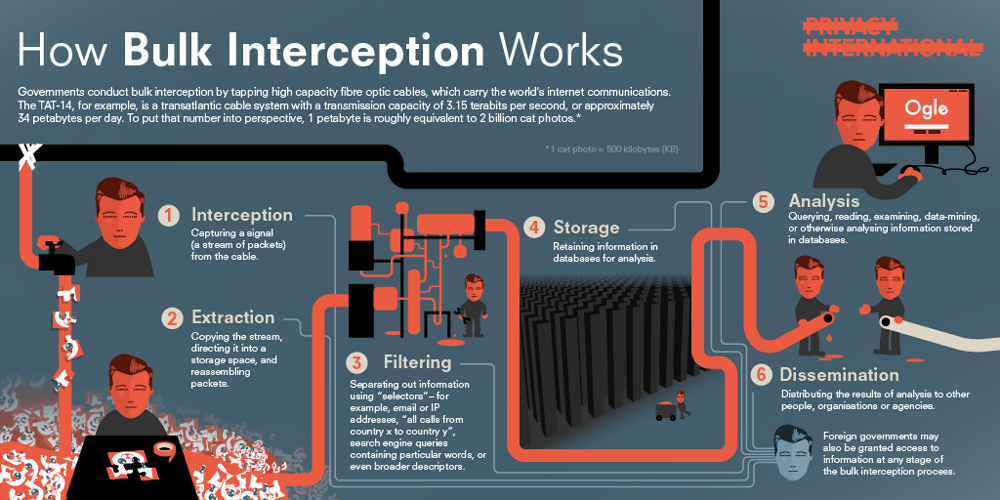

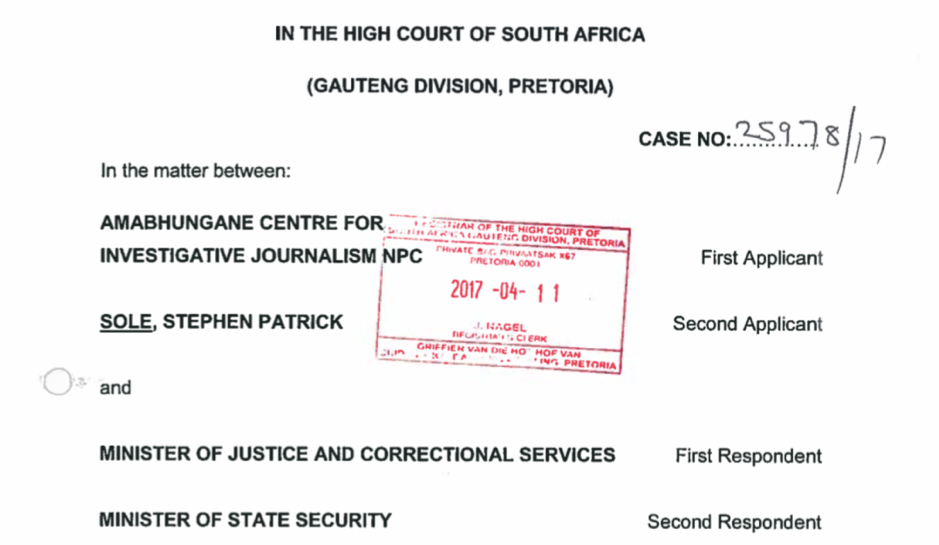

In 2017, the amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism started a legal challenge after learning that state spies had been recording journalist Sam Sole’s phone communications for (at least) six months in 2008 during the ‘Spy Tapes’ era.

The two applicants – the amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism and journalist Stephen Patrick Sole – challenged the constitutionality of certain sections of the regulatory framework of South Africa. Specifically, they argue that the Regulation of Interception of Communications Act of 2002 (RICA) and the National Security Act of 1994 (NSIA) violate the right to privacy and the Court should therefore declare them as unconstitutional. Privacy International together with the Right2Know intervened to the case as friends of the court.

In a common affidavit, in the course of this case, the South African intelligence agencies – that is the Minister of State Security, the Office for Interception of Centres, the National Communications Centre and the State Security Agency – briefly describe their bulk interception practices in a couple of pages.

In their common affidavit, the South African intelligence agencies admit to the “tapping or recording of transnational signals, including, in some cases, undersea fibre optic cables.” They claim to intercept “any communication that emanates from outside the borders of the Republic (in this case, South Africa) and passes through or ends in the Republic.”

This bulk interception, according to them, aims to ensure that the “state is secured against transnational threats”. Specifically, “[t]he Signal Intelligence collection process is informed by the National Intelligence Priorities, which include imminent and anticipated threats. It also covers information about organised crime and terrorist related activities. Bulk [surveillance] also deals with areas like food security, water security and illicit financial flows.” (emphasis added)

They claim that such bulk surveillance is not directed against individuals, even though a couple of paragraphs below they admit that “[i]t helps the State identify individuals and groups and entities across the country's borders and overseas that pose a threat to the security of the nation.”

While arguing that bulk interception is aimed at foreign signal intelligence, they admit that the system cannot distinguish between foreign and domestic communication. “The direction of communication can only accurately be determined by human intervention and analysis after the interception and recording process has been completed.” They add “[b]ulk surveillance systems cannot distinguish whether a communication emanates from outside the borders or simply passes through or ends in the Republic of South Africa.”

They briefly refer to the existence of multiple back-ups of the recorded information stored within the Data Centre but also in other un-identified locations. Allegedly, no human intervention is required for these processes and “[t]his stored information is strictly accessed by only authorised technical personnel. This process is also automated, executed and managed internally by the system.”

Finally, they reassure the court that “RICA provides for sufficient safeguards designed to ensure that Bulk surveillance takes place in an environment that protects abuse and unlawful invasion of privacy.” However, they do not provide any further information.

What comes next?

These confessions constitute a positive step towards transparency and regulation. Several myths with regard to their operation are exposed. For instance, the persistent argument by governments that such powers collect only foreign intelligence signals is refuted. The South African intelligence agencies admit that the system cannot distinguish between foreign and domestic communication and human intervention is necessary to make this distinction.

These programmes have run in secret since the early 2000s. However, it took multiple reports by whistleblowers and journalists, the sensation caused by the Snowden disclosures and persistent legal action by civil society actors for these two governments to admit the existence of some of the most pervasive surveillance programmes in human history.

Any surveillance, by its nature, impacts on personal privacy, but the impact of mass surveillance where millions of people are potentially spied upon without being suspected of any wrongdoing is devastating and not just for privacy. It threatens the foundations of democratic societies and puts at risk our fundamental freedoms. The feeling of constant surveillance may have unprecedented widespread negative effects on the way users exercise their freedoms, particularly freedom of expression – often referred to as the chilling effect of surveillance.

Last July, at OrgCon 2019, Edward Snowden remarked: “People think of 2013 as a surveillance story, but it was really a democracy story”. The European Court of Human Rights also recently highlighted that “a system of secret surveillance for the protection of national security may undermine or even destroy democracy under the cloak of defending it.”

Yet and despite all these assertions, there is still a lot we do not know about how the British and the South African bulk interception programmes function. In South Africa, according to the intelligence agencies view, the legal basis for bulk interception is still implicit in already existing provisions of RICA. Bulk interception is not regulated separately.

While these partial disclosures are ongoing, it is necessary to have further public discussions on whether such degree of interference with our privacy should even be permitted.

Two courts in two far ends of the globe – one in the North and the other in the South – have now the opportunity to prohibit bulk surveillance practices and ensure that our privacy is protected. The Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights and the South African High Court in Pretoria have an opportunity to declare that bulk interception of internet traffic is a serious violation of the right to privacy.

To be continued…

*Image 1: cable data by Greg Mahlknecht, map by Openstreetmap contributors [CC BY-SA 2.0]