A documentation of data exploitation in sexual and reproductive rights

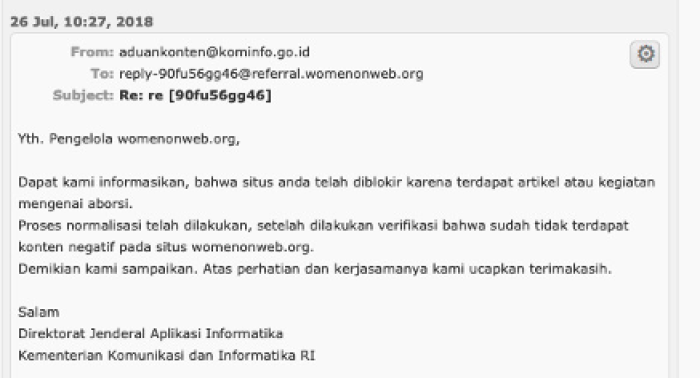

This Privacy International report documents 10 data exploitative technologies and tactics being developed to delay or curtail access to reproductive healthcare globally.

- PI has documented a series data exploitative tactics that the opposition is using to delay or curtail access to reproductive healthcare.

The organised opposition to sexual and reproductive rights has gone digital. Data exploitative tech is being developed that is capable of obtaining vast amounts of intimate information about people’s reproductive health, and delaying or curtailing access to reproductive healthcare.

Technology provides incredible opportunities to democratise access to reproductive health information, services, and care. It can play a vital role in protecting the lives of those needing sexual and reproductive health information and care, especially in places where access is otherwise impossible.

Simultaneously, those standing in opposition to reproductive rights are developing and promoting digital tools and tactics that attempt to curtail the ability of people to exercise their reproductive rights.

The exploitation of data by the opposition movement is just beginning. As this report shows, the utility of data to rapidly and precisely target content online, to uncover a person’s location, to understand people’s mindsets and lifestyles, is not unknown to those fighting against reproductive rights. Privacy experts and reproductive rights organisations globally must work together to expose and advocate against such data exploitation.

PI has documented 10 data exploitative tactics that the opposition is using to delay or curtail access to reproductive healthcare.

These tactics include:

- Developing digital dossiers about those seeking pregnancy options: the system appears to be able to collect information such as name, address, email address, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangement, education, income source, alcohol, cigarette, and drug intake, medications and medical history, sexual transmitted disease history, name of the referring person/organisation, pregnancy symptoms, pregnancy history, medical testing information, and eventually even ultrasound photos.

- Deploying geo-fencing technology that can reportedly tag and target anti-abortion ads to the phones of people inside reproductive health clinics

- Deploying online chat services, including one that appears to share intimate information about people seeking pregnancy support with a major anti-contraception, anti-abortion organisation based in the US [page 18]

- Developing smartphone apps that request vast amounts of information about people’s menstrual cycles and reproductive health while reportedly “sow[ing] doubt over the safety of birth control” and covertly being funded by “anti-abortion, anti-gay Catholic campaigners”

- Creating fake websites that give “the impression” of offering objective counselling and information about pregnancy options

- Integrating with government operations, including providing “options counselling” to young pregnant migrants in the US

- Developing websites for crisis pregnancy centres that require the centres to use guarded anti-abortion language on “5 medical pages” including about abortion and pregnancy

- Developing honey pot websites that have the potential to mislead people seeking pregnancy information, options, and services [page 40]

- Coordinating international campaigns and trainings promoting an anti-reproductive rights agenda [page 50]

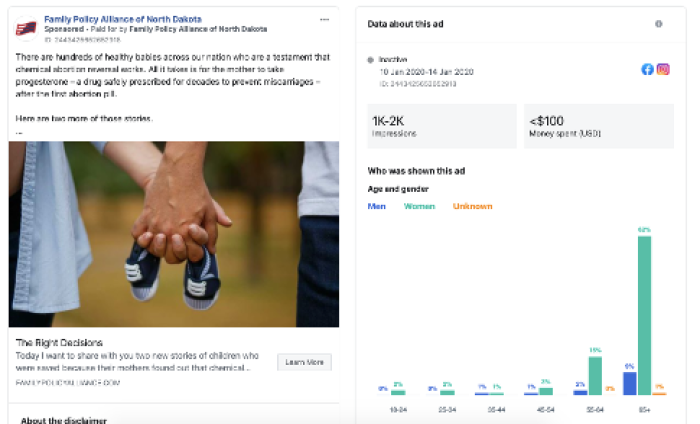

- Deploying targeted ads on social media that promote scientifically dubious health information [page 58]

Selected highlights from the report are available below and the full report is available here.

Reactions to the research

Spokesperson at The British Pregnancy Advisory Service said:

“During the current pandemic, we have seen how technology can be used to expand women’s access to essential reproductive healthcare, for example through the provision of telemedical abortion services.

However, this report shows that at the same time that we are making strides forwards, anti-choice organisations are developing new digital tactics to block women’s access to healthcare. We know that more women will be seeking information and support online because of the closure of GP surgeries and clinics, and this gives anti-choice organisations more opportunities to intercept and redirect women seeking abortion care. These groups are very adept at hiding their true aims, and they can cause real distress to women by providing misinformation and delaying their access to treatment.

Anti-choice groups in the UK copy the tactics and tools of their counterparts overseas, particularly those in USA. Pro-choice advocates must work together on a global level to expose and advocate against this new threat to reproductive rights.”

Programme Advisor at the International Planned Parenthood Federation's Safe Abortion Action Fund said:

"It’s appalling, but unfortunately not surprising, to see anti-choice groups using digital technologies to spread misinformation and fear about abortion.

Abortion is a very safe, and very common medical procedure – a quarter of all pregnancies around the world end in abortion. However, people seeking safe abortion care are regularly met with a barrage of obstacles, fuelled in part by the pervasive stigma and distortion of facts transmitted by anti-abortion groups, which has real life consequences. This false information and propaganda, whether it be from a ‘counsellor’ in a ‘crisis pregnancy centre’ in Uganda, or an advert shared on a phone in the U.S, is a deliberate attempt to target women in a vulnerable moment. These kind of interventions do not make the need for abortion services go away, they simply drive them underground, causing delays and emotional turmoil, and often driving women to unsafe providers where their health is compromised. Everybody who needs abortion care deserves to be able to do so safely, and with privacy and dignity."

Executive Director at Fundación Datos Protegidos, Chile said:

"This report makes us think to what extent patriarchal logic, dynamics, and discourses are transgressing our digital integrity and how the scarce regulation has not been able to stop this situation that seems to be happening more frequently and with a broader scope.

It turns out to be a new and urgent challenge to tackle how digital data is used to control women's sexuality, once again. Moreover, it opens the question of whether how we have understood data treatment and its use are inclusive about problems that are not associated with data traffic itself, but instead with the discursive and political dispute about bodies through the data of people.

Moreover, the lack of an adequate institutional framework to effectively guarantee the protection of personal data and the privacy of people in Chile makes the local panorama even more complicated within the context of international human rights obligations."

Senior Policy Manager at the Guttmacher Institute said:

“Restricting comprehensive counselling and referrals for all pregnancy options seriously jeopardises pregnant people’s health and well-being. This danger is exacerbated further in the case of immigrant youth in [US] government custody, as these youth are essentially forced into the course of care that the government makes available to them. That the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the agency in charge of caring for these youth, would not only restrict their reproductive decisions by funnelling them to fake women’s health centres, but also breach patient confidentiality protections, is untenable.”

Spokesperson from the Abortion Support Network said:

“The level of organisation and determination of these anti-abortion groups is terrifying. The way they are able to replicate their websites, processes, language and imagery, seeking to intimidate, scare and delay abortion-seekers, is worrying. Unfortunately, it’s another example of the way in which anti-abortion groups are so well-funded and well-organised. We need to make sure that their misleading, misinforming and inaccurate websites are shown up for what they are.”

Senior Policy Advisor for Ipas said:

“Access to information and privacy are keystones to supporting the human right to health. The biased and inaccurate information circulated by FEMM, coupled with the privacy risks inherent in their app, raise major red flags for the reproductive rights community.”

Founder, Transparent Referendum Initiative in Ireland said:

"This paper provides a much needed call to action for privacy and reproductive rights activists to work together to address one of the most violating misuses of technology to emerge over the past decade. The report paints a picture of privacy eroding tactics deployed in order to deceive, exploit, undermine and politicise women in crisis. The use of these tactics in the battle for reproductive rights is, in my opinion, the worst case scenario for those of us concerned about the ad tech driven internet and its implication for human rights."

A documentation of data exploitation in sexual and reproductive rights

Part 1: Methods of data exploitation by the opposition

“We believe we’re better together, and so is our data. Knowing the real-time trends of the larger life-affirming community is a crucial, yet untapped gateway to breakthrough success on the local level—until now, that is.

Crafted by a team of professional healthcare software developers, Next Level CMS also closes a key informational gap within local centers by streamlining intake and data collection to unleash the power of woman-centered service.” Heartbeat International website

“[F]or the first time in human history, we have the capacity to collect and store enormous amounts of detailed personal data for our interpretation and application. Fertility charting is exactly that! And it is on the rise among women of all ages”. The Western Regional Director at TeenSTAR, which works globally to “teach chastity to adolescents”.

Data exploitation has increased in most areas of day-to-day life – companies covertly collect vast amounts of intimate information about people, political parties buy access to huge data sets and micro target ads at voters, smartphone apps send data to third parties without people being aware, and the list goes on. As this report shows, groups in opposition to reproductive rights, such as access to contraception, safe abortion care, medically accurate sexual health information, and more, are also exploiting people’s data to delay and curtail access to vital healthcare.

Tools to streamline data collection and centralisation

Next Level Center Management Solution

Next Level Center Management Solution is a system developed by Heartbeat International, a US-based anti-contraceptive, anti-abortion organisation that runs a global affiliate network of crisis pregnancy centres.

In 2017, Heartbeat International unveiled the Next Level Center Management Solution (CMS) and began promoting it to their 700+ pregnancy centre affiliates. Heartbeat International markets the software as a system that “[m]akes seamless data collection possible for pregnancy centres”. They say that it “allows information to move from the receptionist to the client, from the client to the coach or mentor, and from the mentor to the nurse’s office”, and visualise the system as data streams flowing from individual pregnancy centres to a centralised cloud.

Source: Next Level website

The system appears to unify what questions people are asked when seeking a centre’s help, and to centralise the information that visitors to anti-abortion centres are asked to provide during their visit. The types of information that is collected, which is visible in a promotional video on Next Level’s website, includes name, address, email address, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangement, education, income source, alcohol, cigarette, and drug intake, medications and medical history, sexual transmitted disease history, name of the referring person/organisation, pregnancy symptoms, pregnancy history, medical testing information, and eventually even ultrasound photos.

Next Level’s privacy policy states that the company “may share such information with Next Level affiliates, partners, vendors, or contract organizations, or as legally necessary”, and provides no further information about how people’s personal information is shared or analysed within Heartbeat’s network of 2,700 affiliate organisations and partners, or outside of this network.

In an email to PI, Heartbeat President Jor-El Godsey said that “All data of a personal identifying nature captured by Heartbeat International and its subsidiary programs is protected and kept confidential as a matter of our continuing commitment to confidentiality in accordance with applicable laws of the U.S. and relevant nations. To improve our services and understand the changing needs of those we seek to serve Heartbeat uses only aggregated and de-identified information to formulate and analyze trends.”

In 2018 Heartbeat reported that its affiliates had served 1.5 million clients. Heartbeat does not appear to provide information about how and who “de-identifies” information, and at what point such de-identification occurs. To the extent that the de-identification process remains unclear, Next Level, as a part of Heartbeat International, may have access to vast amounts of identifiable information and therefore understanding how such de-identification occurs in crucial.

Geo-fencing technology

In brief, geo-fencing is the creation of a virtual boundary around an area that allows software to trigger a response or alert when a mobile phone enters or leaves an area. When a person enters a geo-fenced area or building, geo-fencing tech can allow a person’s phone to be tagged and then for targeted ads to be sent directly to a person’s phone.

In 2016 an investigation in ReWire News showed that a US marketing company was promoting technology that could send ads directly to the phones of people inside sexual and reproductive health clinics. It was reported that the technology also “has the capability to hand the names and addresses of women seeking abortion care, and those who provide it, over to anti-choice groups”.

According to Rewire News, the marketing company included in a PowerPoint presentation that was sent to prospective clients a slide that said their system could reach “abortion clinics, hospitals, doctors’ offices, colleges, and high schools in the US and Canada, and then “[d]rill down to age and sex””. It went on to say, “We can gather a tremendous amount of information from the [smartphone] ID” and that “some of the break outs include: Gender, age, race, pet owners, Honda owners, online purchases, and much more”.

In the same presentation Rewire News reported that the company said it had “already attempted to ping cell phones for RealOptions and Bethany nearly three million times, and had been able to steer thousands of women to their websites” and that the marketing company had deployed the system around reproductive health centres and methadone clinics in the US states New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, and Missouri. This means that those who visited those centres may have been targeted with crisis pregnancy centre or other anti-abortion ads.

Clients of the marketing company reportedly included RealOptions, a network of crisis pregnancy centres in California which has since merged with The Obria Group and Bethany Christian Services, presumably showing the opposition’s interest in and willingness to spend money to deploy such technology.

In 2017 the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office alleged that the geo-fencing system violated the Massachusetts Consumer Protection Act, due to how it covertly tracked people and disclosed sensitive information to third-party advertisers. The company has since agreed to not use the technology at or near healthcare facilities in the US state of Massachusetts.

Website chat services

Option Line

Option Line is a website, chat service, and phone number that was co-developed by the US organisations Heartbeat International and Care Net and deployed on crisis pregnancy centre websites. A 2018 Heartbeat International report said that over 400,000 people have been served on Option Line. Option Line’s chat service appears on many Heartbeat International affiliated crisis pregnancy centre websites (for example here, here, here).

Prior to beginning a chat, the Option Line chat interface requires visitors to enter their name, demographic information, location information, as well as if someone is considering an abortion. Only after submitting this personal information does the chat begin.

Example of crisis pregnancy centre website developed by Heartbeat International’s Extend Web Services, and with the Option Line chat open.

Privacy International has seen technical documentation, which has since been removed from Extend Web Service’s website, [available here – accessed February 2020] stating that Heartbeat International’s Next Level Center Management Solution provides for an “Option Line User Interface”. From the documentation, the interface seems to provide an option to create a Next Level profile when a person interacts with Option Line.

PI wanted to understand if and how Heartbeat International obtains information about those using its services, including Option Line. The intimate nature of what could be discussed in Option Line chats and the personal information that is required to be provided prior to being able to use an Option Line chat, such as name and location information, and information about a person’s mindset, clearly shows how important it is to understand if and how the chat information is shared, including whether that is back to Heartbeat International.

In March 2020 a Privacy International staff member began an Option Line chat on a Heartbeat International-affiliated crisis pregnancy centre operating within the EU. To seek to understand if and how the data is shared, the PI staff member subsequently sent a subject access request under the EU's data protection law - the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) - to the crisis pregnancy centre, as well as Extend Web Services, Heartbeat International, Option Line, and Next Level Center Management Solution - all of which are Heartbeat International business units. Subject access requests under the GDPR allow a person to ask a company or organisation for a copy of their personal data plus information about it - such as how it’s used, the source of the information and with whom it has been shared.

Extend Web Services, Heartbeat International, and Option Line all told PI by email that they held personal data about the requesting staff member (namely their name, zip code and IP address). Although they were at pains to point out that this was recorded by a third-party system, Live Chat, Inc.

Both the crisis pregnancy centre and Next Level Center Management Solution said that they did not hold personal data about the requestor.

These responses seem to indicate that people using Option Line, no matter where they are physically located, are inadvertently having the information that they are required to provide prior to using the chat, sent to Heartbeat International and Extend Web Services, not to mention the third party Live Chat Inc, a commercial chat bot provider used by large brands such as Ikea.

This seems to illustrate that Heartbeat International could have vast amounts of intimate information about people seeking pregnancy support, including their names, location, and more.

Other crisis pregnancy chat services

PI’s International Network partners who worked with PI on this report documented other crisis pregnancy networks and websites that used similar chat services. The information required prior to beginning a chat varies, and at the time of writing, some of the websites provide no privacy policies.

Embarazo Inesperado [dot] com

Similar to Option Line, prior to being able to use the chat service on Embarazo Inesperado [dot] com, people are required to first provide their name, email address, phone number, and message (or sign in using your Facebook account). At the time of writing, the website does not appear to provide another way for people to make contact other than through the chat service.

From the website, it is unclear to whom the information provided before and during a chat is sent or how it is used; the chat service uses the third-party software Zen Desk. Furthermore, according to PI’s Peruvian partner Hiperderecho, Embarazo Inesperado [dot] com does not appear to have a privacy policy available on the website at the time of writing, even when the website states “Your information is safe. Read our Privacy Notice on the website”.

Screenshot from Embarazo Inesperado [dot] com using Zen Desk.

Data exploitation by smar phone apps

FEMM

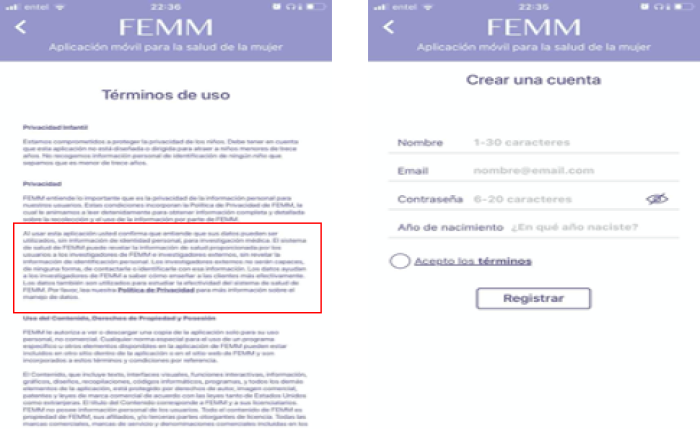

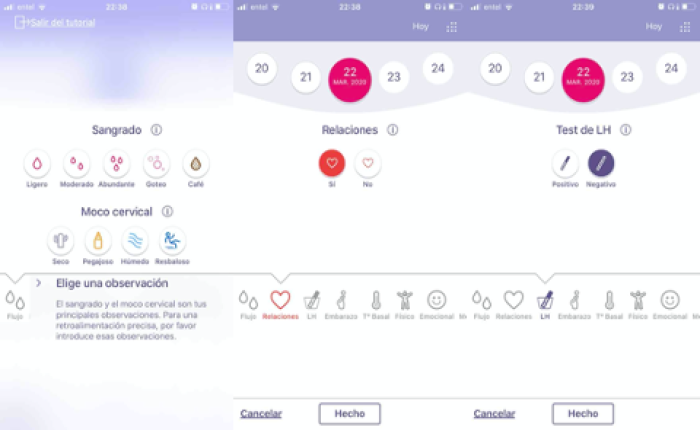

The Fertility Education and Medical Management Foundation or FEMM describes itself as a women’s health program that in part “teaches women to understand their bodies” and “provides accurate medical testing and treatment based on new research and medical protocols”. As a part of the system, the FEMM Foundation developed the FEMM app which requests intimate information about people’s menstrual cycles and reproductive health. The FEMM Foundation advocates against contraception and promotes the app as “just as effective but more attractive because it does not risk unpleasant side effects [of contraception] and also empowers women to monitor their health”.

In 2019 it was revealed by the Guardian that the FEMM app “is funded and led by anti-abortion, anti-gay Catholic campaigners” and “sows doubt over the safety of birth control”. According to the Guardian, FEMM is backed financially by the Chiaroscuro Foundation, which is primarily funded by Sean Fieler. Sean Fieler is a prominent donor to Conservative organisations in the US.

The Guardian reported that the FEMM app has been downloaded more than 400,000 times since its launch in 2015. The app is available in English, French, Hungarian, Portuguese, and Spanish.

Located at the same New York City address, is the Reproductive Health Research Institute. According to a 2018 annual report, “FEMM collaborates with the Reproductive Health Research Institute in the development of medical research, protocols, and medical training”. According to the Guardian, medical advisors working with the Reproductive Health Research Institute are not licensed to practice medicine in the US and are tied to a Catholic university in Chile. In addition to the New York City address, the Institute lists an address in Santiago, Chile on its website.

Also located at the same New York City address of both FEMM and the Reproductive Health Research Institute, is the World Youth Alliance. The founder of the World Youth Alliance is also listed the CEO of the FEMM Foundation. The World Youth Alliance works at the United Nations, European Union, and Organization of American States to in part advocate against abortion and promote the FEMM app around the world.

The apparently close relationship between FEMM, the Reproductive Health Research Institute, and the World Youth Alliance is concerning. The FEMM App Privacy Policy does little to assuage these concerns, as it states that the FEMM Health System may disclose, in a non-identifiable way, personal health information provided by users to FEMM researchers and third-party researchers. The data is said to “help FEMM researchers understand how FEMM can teach clients more effectively” and to be “used to study the effectiveness of the FEMM Health System”. Questions should be asked about how is the data collected from those using the app globally is analysed and potentially used by the Reproductive Health Research Institute, as well as how any research findings are then used by the World Youth Alliance in their international advocacy against reproductive rights.

According to the Guardian, even while the app collects personal information about mood and health from users, the app does not currently aim to monetise such data or share such data with third parties. In the FEMM privacy fact sheet, the organisation declares that "FEMM never shares or sells data with third parties. FEMM is not funded by drug or big pharma companies, ensuring that we are free from commercial bias in our science and information, as well as from pressures to monetize data and information provided to us by our users".

However, this seems to stand in contradiction to their own Privacy Policy [accessed March 2020], which states that FEMM assigns a random number to the app installed in a mobile device: "We use this random number in a manner similar to our use of Cookies as described in this Privacy Policy". In other words, they "may use Cookie information to target certain advertisements to your browser or to determine the popularity of certain content or advertisements". Moreover, they say that the random number cannot be used to identify a person "unless you choose to become a registered user of the App". However, one does not appear to be able to use the app without registering – and registering requires users to provide information including name, email, and date of birth.

Some examples of data collected by the FEMM app: sexual activity, emotional status, temperature, and more – provided to PI by Paz Peña.

Questions should also be raised around the ability for researchers to potentially carry out research with fertility data provided by those using an app and without being necessarily aware of how they data could be used. This becomes even more relevant if this data is used to justify an agenda against reproductive rights.

In response to this research, the Senior Policy Advisor for Ipas, an international women's reproductive health and rights organisation said, “Access to information and privacy are keystones to supporting the human right to health. The biased and inaccurate information circulated by FEMM, coupled with the privacy risks inherent in their app, raise major red flags for the reproductive rights community.”

uCampaign

Data collection and data sharing by political parties and political actors has come under intense criticism and scrutiny over the past years. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have come under particular fire for allowing political campaigns to send targeted messages to voters with no meaningful transparency and accountability.

In addition to buying ads on social media, political parties, political actors, and campaign groups are also developing campaign apps to rally supporters and grassroots activists.

In 2018, Ireland held a referendum to decide whether to repeal the eighth amendment of the Irish Constitution, which made abortion care illegal. Two major campaigns against repealing were the Save the 8th campaign and the LoveBoth Project. Both groups used smart phone apps to mobilise supporters. It has been reported that the apps for both campaigns were developed by the US-based, internationally working company uCampaign. It was further reported that, according to its privacy policy, uCampaign reserved the right to share data “with other organizations, groups, causes, campaigns, political organizations, and [their] clients that [they] believe have similar viewpoints, principles or objectives as [them]”. Other clients of uCampaign include the Trump 2016 presidential campaign, the US Republican National Committee, the major US anti-abortion group Susan B. Anthony List, and the UK Vote Leave campaign. Sean Fieler, who the Guardian reported as financially supporting FEMM, also reportedly provided seed funding for uCampaign.

That uCampaign’s privacy policy enables it to share personal information with groups with similar viewpoints, principles, or objectives may result in people’s personal information, such as their names, email, addresses, phone numbers, location information, images, and more, being shared and swapped with an untold number of people. Users wouldn’t necessarily be aware that such sharing was happening, and therefore be unable to prevent it.

This demonstrates how users can be left in the dark about how apps, set up ostensibly for one purpose, can be in reality set up to maximise how much data is collected about those using the apps, and exploiting that information in ways people could never imagine.

Fake websites

Fake Irish Health Services website

Following the enactment of the Health (Termination of Pregnancy) Act, the Irish Health Services Executive (HSE) announced it was launching a website to provide people with the full range of unintended pregnancy options and information, including about abortion. Shortly after the website was announced, a website with very similar URL went online, which attempted to misdirect people that were seeking advice and care away from the real HSE website.

It was reported that the fake website gave “the impression… [of] offering services in connection with the HSE [Irish Health Services], or that objective counselling and information services are being provided”. The fake website reportedly listed a phone number to call and promised a free ultrasound.

The Irish Family Planning Association told PI by email that "the HSE claimed (correctly) in court that the fake website was “inappropriately offering pregnancy scans, is trying to convince women not to go ahead with abortions, or berating those who have chosen to undergo a termination"; this kind of harassment of people as they tried to access healthcare was distressing, unethical and may well have delayed some pregnant women or girls and forced them to leave the state to access abortion care, with all the distress and financial burden that entailed."

The HSE issued court proceedings against the man behind the fake website and a temporary injunction was issued against him in February 2019. This was made permanent in May 2019.

However, it remains unknown how many people needing help called the phone number on the fake website, which was reportedly the phone number of the man that set up the fake site. It’s also unclear how many people provided information about themselves to the man or obtained an ultrasound from him, or the effect of realising that the man was not from the Irish Health Services Executive had on those who sought help from the website. It is further unclear how many people were forced to travel to the UK after being delayed from accessing abortion care in Ireland due to the actions of the person behind the fake website.

Part 2: Methods of data sharing by the opposition

“At the most extreme end - we know that anti-abortion organisations in Malta shared abortion-seekers’ data with each other and with anti-abortion organisations in Ireland who then contacted the client pretending to be the British Pregnancy Resource Centre in the UK.” Abortion Support Network, in an interview with Privacy International

In addition to the above methods of data collection, covert data sharing is equally problematic. People seeking reproductive health information and services have the right to have their information kept confidential and private. However, as outlined below, there are numerous examples of both formal and informal data sharing, some of which have resulted in either delaying or denying care, effectively interfering with people’s reproductive rights.

Government collaboration with the opposition

The role of national governments in the provision of reproductive healthcare varies greatly between countries. Below are some examples that demonstrate the apparent closeness of some governments to opposition groups.

Data exploitative initiatives

National Ministry of Health and Social Development Hotline – Argentina

According to the Argentine paper Pagina12, in early 2019, the National Ministry of Health and Social Development in Argentina and the National Network of support for women with vulnerable pregnancies - a national network of opposition organisations - signed an agreement to create a 0-800 hotline to “facilitate the promotion” of the Network throughout the country.

The agreement, which has since been taken offline, was reportedly going to create a 0-800 number to communicate with more than 100 centres for “the referral of cases that require accompaniment of pregnant women in vulnerable conditions”. This centre was to be led by members of different churches throughout the country “that will take on this challenge of providing mothers with the necessary elements for care of their babies, in addition to providing accompaniment and support”.

The Ministry eventually decided not to move forward with the hotline due to the project being out of step with the Plan ENIA (National Plan against unintentional pregnancy in adolescence) which says that these types of hotlines must inform pregnant people about the right to abortion.

Large-scale identity programmes – India

According to PI International Network partner Center for Internet and Society (CIS) in India, who worked on this report with PI, hospitals in India are asking those seeking reproductive healthcare to present their Aadhaar cards (centralised biometric identification) in order to receive such care. Further, according to CIS, any person hoping to take part in maternal health welfare programmes must present their Aadhaar cards at public hospitals. CIS told PI that without any official government notices, many public hospitals are demanding Aadhaar cards before allowing women to access of reproductive health procedures. In a notable case in 2017, a Chandigarh hospital reportedly refused to provide services to a patient who did not have an Aadhaar card.

This has led to the denial of essential services and fundamental rights to those who have not been able to enrol themselves in the Aadhaar database, and in the case of benefits, opened a bank account and seeded it with the Aadhaar.

According to CIS, not only does this actively restrict some people from accessing services, but it collects data on those seeking reproductive health care services which is then centralised and shared among associated parties. Associated parties include anyone who has access to an individual’s Aadhaar number and can request information through the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI). According to CIS, this includes most government bodies and since 2019, banks, telecoms, and more.

Data leaks are also common in this digital system. For example, in April 2019, a government agency data breach made the health records of 12.5 million pregnant women available online. CIS told PI that the surveillance brought on by the Aadhaar is unprecedented as it collects data from birth to death, documenting every interaction citizens have with the state in a centralised database that is also linked to the biometrics of citizens.

Furthermore, according to CIS, the Indian Health Management Information System and the national Mother and Child Tracking System both collect data on maternal health in the ante-natal and postnatal periods. CIS told PI that in 2016 the minister for Women and Child Development proposed mandatorily linking such reproductive services with the Aadhaar card for further data linking and centralisation, and for the provision of benefits schemes. Compounding data collection in this way, while having meagre data protection infrastructure in place, puts the confidentiality and privacy of those seeking reproductive healthcare in jeopardy. This is especially dangerous for those who already face barriers to access (i.e. young, unmarried, from rural regions, migrants etc).

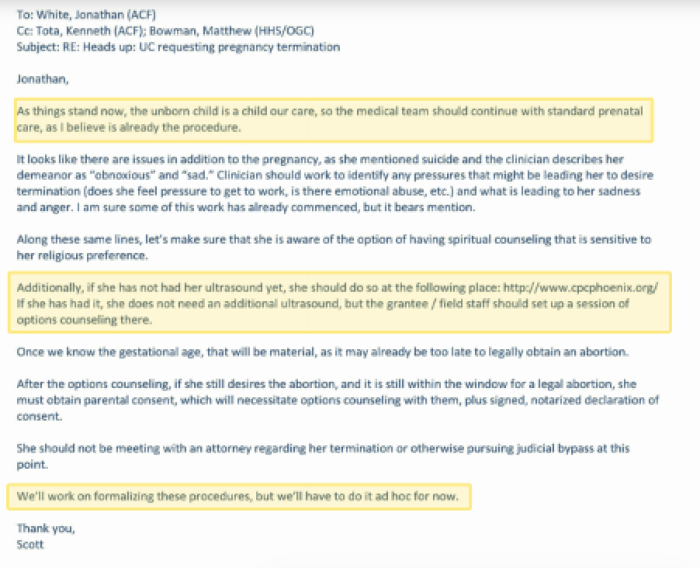

Data sharing between crisis pregnancy centres and immigration authorities

In 2017 it was revealed that the US Office of Refugee Resettlement, which is responsible for the care of unaccompanied migrant children in the US, was sending pregnant migrants seeking abortion care to “options” counselling sessions at crisis pregnancy centres. It was further reported that the Office of Refugee Resettlement had an internal list of approved crisis pregnancy centres to which the pregnant people could be sent for the counselling sessions, and that the list was developed by Heartbeat International. It was reported that all 60 approved centres appear in Heartbeat International’s database of like-minded pregnancy centres and all but eight are “affiliates” of the organisation. Heartbeat International and its affiliates do not refer for or provide abortion care and they do not promote the use of contraceptives.

It remains unclear what, if any, data sharing agreements are in place to ensure that pregnant migrant’s privacy is upheld and their information kept confidential. However, from published internal Office of Refugee Resettlement emails, it appears that information is potentially being shared between crisis pregnancy centres and the Office of Refugee Resettlement. The emails show that the former head of the Office directed staff to send one pregnant migrant who was seeking an abortion to a crisis pregnancy centre for an ultrasound and “options counselling”. He said that once the Office knew the gestational age, “that will be material, as it may already be too late to legally obtain an abortion”, appearing to demonstrate that information obtained by crisis pregnancy centres working with the Office Refugee Resettlement is shared back with the Office. This could potentially include intimate information disclosed during the “options” counselling sessions.

Screenshot of an internal email from the former Director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement directing staff to send a pregnant migrant to the crisis pregnancy centre CPC Phoenix (now Choices).

When asked by PI about this, the Guttmacher Institute’s Senior Policy Manager said “Restricting comprehensive counselling and referrals for all pregnancy options seriously jeopardises pregnant people’s health and well-being. This danger is exacerbated further in the case of immigrant youth in [US] government custody, as these youth are essentially forced into the course of care that the government makes available to them. That the Office of Refugee Resettlement, the agency in charge of caring for these youth, would not only restrict their reproductive decisions by funnelling them to fake women’s health centres, but also breach patient confidentiality protections, is untenable.”

Period tracking by governments and state institutions

In the US, the Director of the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services was found to have created a spreadsheet tracking the menstrual cycles of patients to the state’s only abortion clinic. The spreadsheet was reportedly made at the male Director’s request to “help identify patients who had undergone failed abortions”. The spreadsheet was reportedly based on medical records that were available during the state’s annual inspection of the abortion clinic, and included medical identification numbers, dates of medical procedures, and the gestational ages of fetuses – the health department then reportedly calculated the date of the last menstrual period of each patients and included that within the spreadsheet. It was reported that the spreadsheet was emailed between health department employees “with the title “Director’s Request”” and “the subject line.. was “Duplicate ITOPs with last normal menses date”.

Informal data sharing among the opposition

Informal data sharing between like-minded groups is also happening. For example in 2019, the Abortion Support Network, the British Pregnancy Advisory Service, and Voice for Choice Malta issued a press release that warned that opposition groups in Malta, where abortion is illegal, had shared the contact details of people seeking abortion care with an opposition group in Ireland. The Abortion Support Network told PI that this led to people seeking abortion care to be contacted by an Irish person pretending to be from a legitimate abortion provider in the UK and being sent abusive text messages and being visited at their home addresses.

Part 3: Methods of spreading misleading health information online

“Of 64 reviewed websites…58% of sites did not provide notice that Pregnancy Resource Centers do not provide or refer for abortion, and 53% included false or misleading statements regarding the need to make a decision about abortion or links between abortion and mental health problems or breast cancer…Most sites (89%) did not provide notice that Pregnancy Resource Centers do not provide or refer for contraceptives. Two sites (3%) advertised unproven “abortion reversal” services.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Services and Related Health Information on Pregnancy Resource Center Websites: A Statewide Content Analysis

“Tactics are often presumed to be attempts to convince women that abortion is bad and harmful, and that they should change their minds e.g. telling them abortion causes depression, infertility or breast cancer, that they will regret their decision, and showing misleading photos and videos, offering support when the child is born and presenting adoption as a viable alternative. Obviously, this does happen, but much of the time the primary tactics used are to delay women from accessing care by misleading them.” Abortion Support Network, in an interview with Privacy International

“We are experts at making sure your website is attracting the abortion-minded client and representing your center in a way that will make your clients feel comfortable with the service they will receive.” The company says it develops websites that attract “abortion-minded” people, make them “feel comfortable”, and “effectively reach women in crisis online”. From the about us page on Extend Web Service’s website – Heartbeat International’s website design company

A well-known tactic of opposition groups is to spread and promote misleading health information. A relatively new component of how such information is spread, is through social media ad targeting systems, through which opposition groups can target misleading health information even more precisely and rapidly. There are now companies that assist opposition groups to quickly develop a web presence, and help them reach and effectively communicate to those seeking information and services, without making the limitations of their services immediately apparent.

Coordinated use of misleading health information online

Extend Web Services

Extend Web Services is a web design company set up and run by Heartbeat International to develop websites for crisis pregnancy centres and other related organisations.

Heartbeat International requires clients of Extend Web Services to use Heartbeat-provided language on “5 medical pages”. An Extend representative told PI that Heartbeat International restricts the ability for their clients to change the language used on “5 medical pages” which are “provided and managed by Extend Web Services/Heartbeat International”. These pages, the representative told PI, include: “Abortion Information/Education”, “Abortion Recovery”, “Sexual Health”, “Pregnancy”, and “Emergency Contraception”. The representative further told PI “All other pages of the website are able to be fully customized by the client in terms of content, imagery, etc. They are able to request one of the 5 pages listed above to be completely removed from the site if they don't like the content. They can provide their own content to fully replace one of those pages as well - they just aren't allowed to edit the content on those pages that we provided.”

The content on the “5 medical pages” is guardedly anti-abortion and misleading. For example, the “Abortion Information/Education” page says “Even though pregnancy tests are generally accurate, it can also be a good idea to get an ultrasound. This can tell you if your pregnancy is viable”. This language reflects the opposition’s desire to require those seeking an abortion to first obtain an ultrasound. It also misleadingly conflates confirming pregnancy viability with obtaining an ultrasound, while the person conducting the ultrasound may not be trained to read an ultrasound.

In response to this research, the Abortion Support Network told PI “We know that our clients regularly seek information online before they find us, or actual, reputable providers of care. We know that they find websites, like those provided by Extend Web Services and Heartbeat International, because we hear about the inaccurate, dangerous misinformation they’ve found online. Reading websites like these can make women and pregnant people nervous about seeking the care they want, and we hear from clients who ask us “Am I going to hell because I’m having an abortion?” – it’s those clients who are impacted by websites like these.”

In response to the research, Dr. Andrea Swartzendruber, who is principal investigator for multiple studies investigating crisis pregnancy centres in the US state of Georgia, and is an assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Georgia College of Public Health said, “This information is new to me but helps explain why some of the exact same information is found on many CPC websites. My research shows that much of the health information included on CPC websites is uncited and many of the citations that are provided are broken links or do not reference scientific evidence or organizations. In the United States, we found that CPCs commonly misstate that ultrasound technology can predict miscarriage. Advocacy groups have reported instances that suggest that CPC staff conducting ultrasounds are untrained and CPCs are typically staffed by volunteers and lay people. However, to my knowledge, the qualifications and clinical licensures of CPC staff has not been systematically studied or reported.”

Honey pot websites

A well-known tactic of the opposition and is to set up friendly-looking websites, such as the Extend Web Services templates, to intercept people seeking reproductive health information and services. We’ve included a handful of examples below.

Help Centres for Women (“CAMs”) in Latin America

A recent report from Open Democracy documented the experiences of people seeking pregnancy support, options, and services from Heartbeat International-affiliated crisis pregnancy centres. In one instance, an Open Democracy researcher visited two CAM pages promoting services in Mexico: a freestanding website, and a Facebook page associated to a CAM. The researcher then contacted these two organisations to arrange a meeting. Open Democracy reported that representatives from the organisations asked the person about her pregnancy, about her reasons for wanting to obtain an abortion, about the “father”, and gave her false information on bleeding.

For example, working with Privacy International, the Argentina-based organisation Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género (ELA), researched CAMs work in the country.

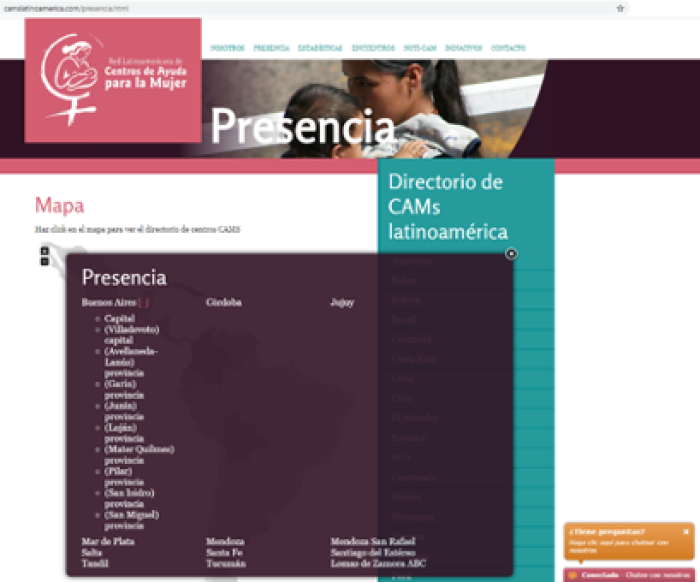

CAMs Latinoamerica

This above screenshot is of the homepage of the website of CAMs Latinoamerica. According to ELA, they describe themselves as “The Latin American network of Aid Centres for Women is a non-profit network, committed to defending human life from the moment of conception until natural death, in accordance with the Magisterium of the Roman and Apostolic Catholic Church.”

As the above screenshot shows, the website (the turquoise square at the far left) says that “The Help Centre for Women (CAM), seeks to help pregnant women who have decided to abort, to freely choose to accept their motherhood, in order to protect and preserve their dignity, achieving impact on their family and their familiar surroundings.”- The second square says: “We work in unity with the Aid Centres for Women, in order to save lives from abortion throughout Latin America; all through the exchange of experiences and information, to consolidate the growth of the Culture of Life.”

Even though the website mentions that they have offices in 19 countries, the only direct contact information they offer is from Mexico. ELA told PI that the site appears to provide contact information for the centres outside of Mexico when a person contacts them via the chat service.

According to ELA, the website also has a “statistics” section which contains stats about how the centres are being used in different Latin American countries. According to ELA, the information is from 2018 and shows what sort of information about people seeking care is being collected by the centre. The page details the number of women attending different Latin American CAMs, the ages of the women, marital status, gestation status, and reason for seeking an abortion.

Individual CAM websites may also present information in ways that may induce the person seeking care to believe that the centre offers access to specific contraception, and that they are qualified to provide medical advice in relation to its use.

For example, the below screenshot is of a website from a CAM centre in Quito, Ecuador in which they offer information regarding Cytotec (the commercial name for misoprostol) and a phone number to call to discuss its use and effects. However, abortion is illegal in Ecuador except in cases where the life of the pregnant person is in danger or if the pregnancy is the result of the rape of a person with mental disabilities, meaning that it is unlikely that this organisation provides medically accurate information about the medication’s use.

On this website they mention that women will be treated by “personnel highly trained”.

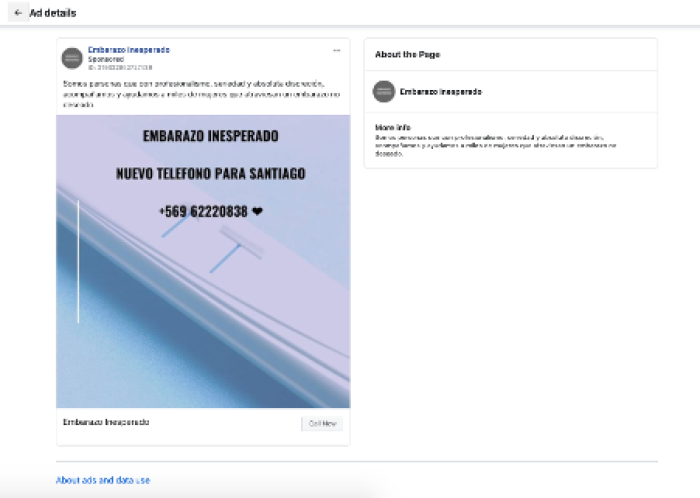

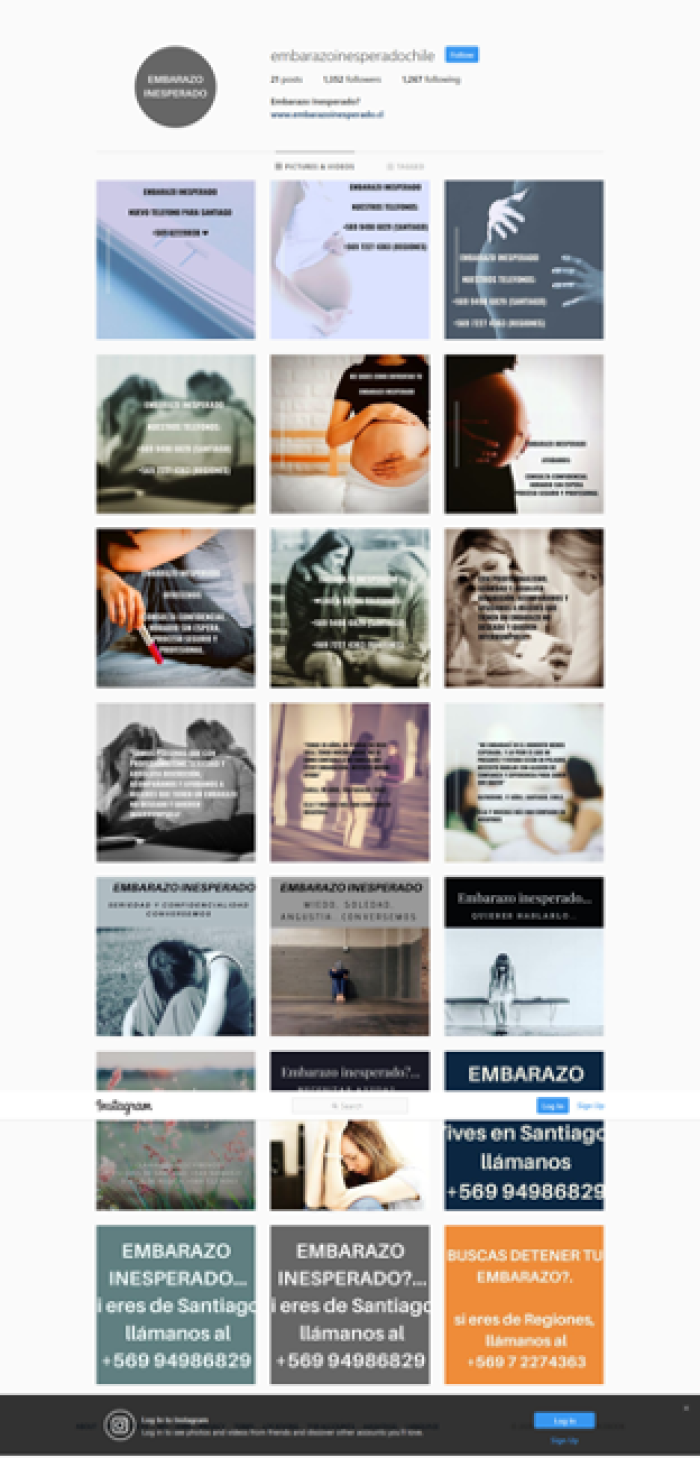

Embarazo Inesperado CAM – Chile

Another example of CAM websites in Latin America comes from Chile, where Paz Peña, who worked with PI on this research, focused on the national Embarazo Inesperado CAM website. The website has a phone number, webchat, and promotes its services on Facebook and Instagram.

Embarazo Inesperado – Chile Instagram page

Despite the CAMs social media presence and modern website, there is markedly little information available about who is behind Embarazo Inesperado in Chile. According to Paz, the Chilean Embarazo Inesperado domain name (.cl) was purchased by a Chilean marketing company. Among the marketing company’s clients are two opposition groups: ISFEM and Red por la Vida y la Familia. Despite being distinct organisations, there are links between them. For example, ISFEM’s vice-president is also the coordinator for Red por la Vida y la Familia; and ISFEM is a member organisation of the Red por la Vida y la Familia network.

While details remain scarce, given the domain was registered by a marketing company working with like-minded opposition groups, questions can be raised about these groups’ relationship with Embarazo Inesperado.

This screenshot apparently shows other clients of the marketing company ETZ En Tus Zapatos SPA. Screenshot provided to PI by Paz Peña.

PI International Network partner Hiperderecho, who worked with PI on this report, spoke with the Peruvian organisation Serena Morena about their thoughts on such honey pot websites. They said: “If you are looking for a safe abortion on a social media, [conservative groups] will contact you and tell you “visit us at this address!”. We have heard stories of women who go to these places, thinking they will receive information on how to get a safe abortion, but as soon as they arrive, they are shown graphic videos and are given presentations with misinformation that aim to dissuade them from aborting. [At this point] these groups already have collected their personal data. We know that in Ecuador they have even used personal data to intimidate these women". Serena Morena is self-described as “A network of women volunteers who accompany women in abortion situations. We do this because in Peru women who decide to abort - even in cases of rape! - are criminalised.”

International trainings and campaigning

International trainings are another way that international opposition organisations can disseminate talking points, develop campaign ideas, and train international partners on a variety of topics.

CitizenGo

CitizenGO is an international ultraconservative online campaign and advocacy platform headquartered in Spain. It promotes petitions against same sex marriage, abortion, transgender rights, and more, and reportedly has over 10 million active members. CitizenGO’s executive director has said that the organisation “provide[s] a complete technological tool, easy, comfortable, and effective, free of charge, so that organisations can dedicate their resources - without distracting them from tools outside their "core" - to more effectively fulfil their mission."

According to the independent consultant Paz Peña, who worked on this report with Privacy International, CitizenGO has several petitions locally in Chile. For example, one petition said that the Chilean State was aiming to control the "soul of our children" because Congress was discussing the constitutional rank of the principle of progressive autonomy of children and adolescents. Another online petition was from the campaign #ConMisHijosNoTeMetas and raised several myths on the gender identity bill that were clarified by specialists in media.

The Population Research Institute and CitizenGO have worked together on campaigns as well. It was reported that the Institute routinely collaborates with CitizenGO and that the Population Research Institute is training CitizenGO staff in the use of political strategy tools and communications. The Institute’s division responsible for “developing tools for political participation” reportedly presented its work at CitizenGO’s Summer School in 2018. It was reported that the central theme at the 2019 CitizenGO board meeting was “to reflect on the new forms of political organisations that have emerged due to the possibilities offered by current information technology”, including “easy affiliation and involvement in political activities through the internet” and more.

CitizenGO also works in Kenya. PI International Network partners the Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network on HIV and AIDS (KELIN) told PI that CitizenGO has launched petitions and campaigns against reproductive healthcare in Kenya. In November 2018, some of Marie Stopes International’s (MSI) reproductive health services were suspended including their abortion services. According to MSI, the organisation is the country’s largest sexual and reproductive health organisation. KELIN told PI that this was due to a petition by members of Citizen Go Africa, which accused Marie Stopes of advocating for abortions through radio stations. This resulted in the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Board (the “KMPDB”) demanding that MSI stop offering abortion services. KELIN told PI that the Kenyan government lifted the ban after an audit by the KMPDB who confirmed that MSI had complied with all laws and regulations and were now able to resume their abortion care services under regular supervision.

KELIN told PI that the Executive Director of the Trust for Indigenous Culture and Health, who campaigned for the ban to be lifted, said the suspension of Marie Stopes services has had a chilling effect on women’s health services and voiced concern over what this means for individual healthcare providers. According to KELIN, the Executive Director further asserted that “reproductive rights advocates faced an increasingly hostile climate and anti-abortion groups always hit hard after success in the realisation of progressive reproductive health services for women in Kenya”.

Heartbeat International

According to Heartbeat International’s website it runs an “Academy” that “offers life-affirming leaders, staff members, volunteers, and supporters” online talks and courses related to, in part, “prenatal diagnostic tests to implementing STI testing in your center”. Other courses include “8 Steps for advancing your social media strategy”, “abortion pill rescue training”, and “is there a link between abortion and breast cancer?”.

The types of courses offered by Heartbeat International are important because they are promoted to the organisation’s international network of affiliated crisis pregnancy centres. Self-described as “the largest worldwide network of pregnancy help organizations”, Heartbeat International runs a network of “over 2,700 affiliated pregnancy help organizations worldwide and affiliated pregnancy help organizations in more than 60 countries” – it says it has “700 affiliate locations outside the US”. The courses that Heartbeat International is promoting to its global affiliate could be used to directly promote misleading health information and misinformation globally.

Open Democracy reports that the one online webinar “developed from the experience of Heartbeat affiliates” teaches hotline operators to discourage or delay women from accessing abortions and emergency contraception. They report that content from another webinar “show[s] how Heartbeat teaches incorrect medical information. For instance, it says that abortion can increase women’s risks of getting cancer and mental illnesses. There is no credible medical evidence for these claims, which have been repeatedly refuted by global health bodies.”

Human Life International (HLI)

Human Life International was established in 1981 and describes themselves as “the world’s largest global pro-life apostolate, with an active network in over 100 countries”. In a 2018 impact report, the organisation says that it organises “the pro-life movement” in “Europe”, parts of Africa, “Asia/Oceania”, and “Latin America” to plan and implement training sessions for “pro-life leaders” and others, and “assist[s] with grassroots movements, such as pregnancy help centres, counseling” and more.

On their website HLI describe contraception as the “root of the culture of death”, abortion as “the consequence of failed contraception” and reproductive technologies as “unethical procedures of procreation”. HLI further state on their website that they collaborate with local, regional and national leaders to provide educational and financial resources to support local programs which instill a greater awareness of the assaults to human life and the family. HLI opposes contraception, in-vitro fertilization, comprehensive sex education, and abortion in all circumstances.

PI International Network partner the Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network on HIV and AIDS (KELIN) told PI that in 2015, HLI started a campaign against condom use by erecting a banner in a rural town in Kenya. KELIN told PI that the campaign was an attempt to condemn the advertising of condoms in all media platforms which they believed were always misleading and encouraging the youth to engage in sexual activities before marriage. In addition, the banner was said to convey the message that condoms cannot prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS. In response, the National Aids Control Council (“NACC”) took hold of the banner and in exchange for its return demanded that the church stop its campaign.. Instead, it was reported, HLI led protests along with five other NGO’s outside the NACC’s building and threatened legal action should the NACC fail to return the banners it had pulled down within 14 days.

KELIN told PI that HLI also publicly denounced the International Conference on Population and Development 25 summit in Nairobi by partnering with other pro-life and pro-family entities and creating an alternative summit dubbed the “Vita et Familia ICPD25”.

Even more notable, KELIN told PI, is HLI’s alleged involvement in a campaign in 2010 created to persuade Kenyans to reject the country’s new constitution which legalized abortion if the woman needed emergency care or her life or health was in danger. KELIN told PI that it was reported that the Catholic Church threatened to reject the 2010 Constitution due to Article 26(4) of the Constitution of Kenya allegedly promoting abortion. KELIN told PI that the HLI Kenya Council chairman at the time was quoted stating that: “the issue should not be whether to legalize abortion, but establishing why it is on the rise”. He also stressed the need to “first address reasons why abortion is rife”. Following the promulgation of the Constitution, HLI were also against the issuance of the 2012 Guidelines. The HLI’s country director reportedly stated: “who has given these individuals the right to decide who should die?”.

Life Matters Worldwide

Life Matters Worldwide describes itself as “help[ing] the Body of Christ articulate the biblical pro-life message in word and deed”. It says that it has “partnered with pro-life ministries to establish and sustain them as effective Gospel outreaches for the glory of God” and has “worked with believers in Eastern Europe, South America, Africa, and Asia”.

In India, Life Matters Worldwide says that it has partnered with at least one hospital in the country and “helped them obtain ultrasound equipment”. PI International Network partner the Center for Internet and Society (CIS) told PI that “by partnering with public hospitals and spreading their message, they are actively working to restrict abortions for rural women in particular through their self-perceived roles as guiders, saviours, and educators”.

Population Research Institute (PRI)

According to PI International Network partner Hiperderecho, the Population Research Institute was founded in 1989 in the United States as a Human Life International research institute, but became independent in 1996. It says it operates in over 30 countries. The office for Latin America is based in Lima, Peru and Hiperderecho told PI that from there different anti-reproductive rights movements have been planned and funded in recent years such as “Marcha por la Vida” against abortion and others against gender policies in education such as “Con Mis Hijos No Te Metas”. Both of these campaigns have been run in other countries in the region as well, such as Argentina, Chile, and Colombia. Members of this organisation reportedly have influence and lobby with public officials and congressmen due to independent investigations detailing lobbying by PRI members.

TeenSTAR

TeenSTAR (“Sexuality Teaching in the Context of Adult Responsibility”) is an educational programme that started in the US – TeenSTAR does not promote the use of contraceptives. The programme appears to be used in 36 countries. For example, according to the Center for Reproductive Rights, Croatia has sponsored the programme for a decade and is seeking to mandate a nearly identical programme. The programme is described by the Center for Reproductive Rights to teach teenagers that contraception “disturbs the essence and the nature of sexual act…can be a protection to a certain extent, but on the other hand, it can give a false sense of security, and sooner or later fail the user”. The Center for Reproductive Rights also says that the programme teaches that, among other things, “masturbation “is a case of severe moral disorder”, intimacy between same-sex couples if counter to “proper” sexual intercourse, analogizing it to sexual harassment and other socially “deviant” phenomena”.

According to the Center for Reproductive Rights, “individual Croatian government officials and an independent commission charged with reviewing Croatia's sex education programs have already concluded that TeenSTAR is neither based in science nor expert medical facts, and that the program fails to address the research and available data on Croatian teenagers' sexual behaviour”.

In a 2018 interview, the Western Regional Director at TeenSTAR in the US, said that “for the first time in human history, we have the capacity to collect and store enormous amounts of detailed personal data for our interpretation and application. Fertility charting is exactly that! And it is on the rise among women of all ages”.

Teen STAR and FEMM have an intersection with Chile. The current Medical Director of the Reproductive Health Research Institute (which collaborates with FEMM) is the current President of TeenSTAR international. She is also an Associate Professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, which has hosted TeenSTAR. It also appears, from the address available on TeenSTAR’s Facebook page and the Chilean address available on the Reproductive Health Research Institute’s website, that TeenSTAR Chile shares an address with the Reproductive Health Research Institute in the country.

World Youth Alliance (WYA)

The World Youth Alliance was founded by the current CEO of the FEMM Foundation in 1999. The WYA says that it “participates directly at the United Nations, European Union, and Organization of American States” and has produced fact sheets and white papers which show that the organisation stands against access to comprehensive sex education, abortion care, and contraception.

According to financial reports, in 2018 WYA provided nearly 400,000 USD in financial support to organisations in Africa, Asia Pacific, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East to, in part, “help promote the dignity of the human person in international policy” and “building a culture of life”. According to its website, WYA has promoted and run FEMM teacher trainings around the world. In a 2018 annual report, the organisation said that FEMM trained over 160 people in Europe and the US and over 150 people as FEMM “health coaches and teachers”.

The Fertility Education and Medical Management Foundation or FEMM describes itself as a women’s health program that in part “teaches women to understand their bodies” and “provides accurate medical testing and treatment based on new research and medical protocols”. However, as mentioned previously, it revealed that the FEMM smartphone app “is funded and led by anti-abortion, anti-gay Catholic campaigners” and “sows doubt over the safety of birth control”. According to the Guardian, FEMM is backed financially by the Chiaroscuro Foundation, which is primarily funded by Sean Fieler. Sean Fieler is a prominent donor to Conservative organisations in the US.

The apparently global reach of the World Youth Alliance and its reported “steady integration in local governments and institutions” to promote a worldview that does not include basic reproductive rights such as access to comprehensive sex education, contraception, and abortion care, is problematic and concerning.

Online ads and social media

A relatively new component of how opposition groups spread misleading health information, is through social media ad targeting systems. These systems allow the opposition to target misleading health information even more precisely and rapidly. While these targeting systems can help those seeking medically accurate reproductive health information and care, they can also be invasive, harmful, and ultimately delay or deny a person from finding and obtaining the care they need.

Juan Pablo Poli, who is a sociologist and member of the Red Nacional de jóvenes para la salud sexual y reproductive in Argentina, a youth-led network promoting gender-inclusive access to sexual and reproductive rights, told PI research partner Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género (ELA), that “There are thousands of instances of disinformation, because, for example, in social networks one can say what they want and especially in this time when people share things without properly reading them. Added to the natural disinformation that people have because these topics are generally not discussed in homes, or in families, or in society in general, or in the media. So it is very counterproductive. And then the anti-rights groups have been able to exploit social media exponentially, perhaps even better than pro-choice groups. Their handling of social media and communication is really impressive. They are very cunning.”

Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram and WhatsApp

Facebook and Facebook-owned Instagram and WhatsApp are used by opposition groups to promote misleading health information about abortion and contraceptives.

The Facebook Ad Library, which has not been fully implemented or made accessible globally by Facebook, can give insights into what opposition groups are advertising, who they are targeting with ads, and what they are saying.

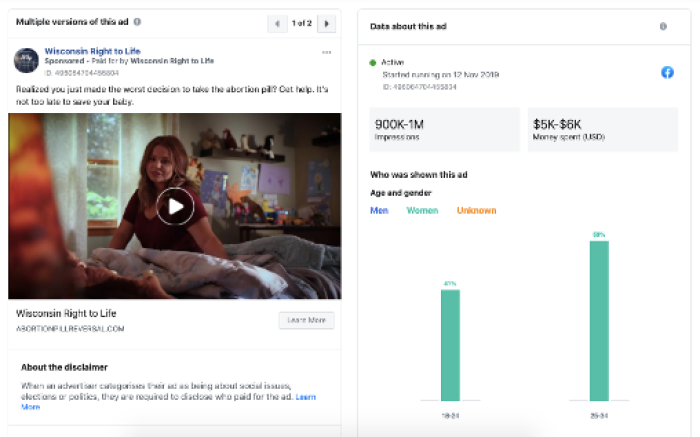

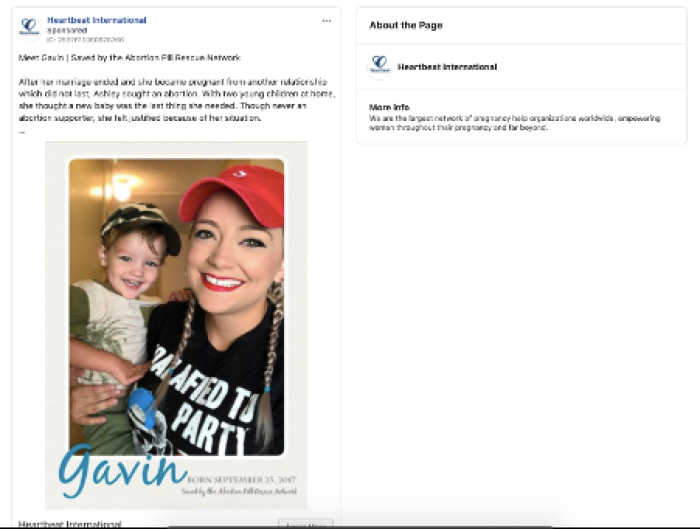

For example, the following three ads from the US, which were accessed by PI on 3 April 2020, promote the scientifically dubious “abortion pill reversal”, which is a programme of Heartbeat International. Dr Monica McLemore, an Associate Professor of Family Health Care Nursing at the University of California, San Francisco described abortion reversal as “a misnomer”. She said, “It is impossible to reverse a procedure. For medication abortion the process described as reversal is scientifically inaccurate. The practice at issue is the untested and unstandardized administration of large doses of progesterone with the intent to overcome the action of the mifepristone. This intervention is not known to be safe or efficacious.” Yet, so-called abortion pill reversal is being promoted via advertising on Facebook and Instagram by opposition groups.

Example 1: This ad is running on Facebook and is being targeted at women ages 18-24 and 25-34.

Example 2: This ad is running on Facebook but appears to have been incorrectly marked as non-political, meaning that no targeting information is available.

Example 3: This ad was run on Facebook and Instagram.

Another example of ads run on social media by opposition groups, is the Chilean Embarazo Inesperado CAM. It offers a stark example of how little information the social media platforms provides about who is behind these ads.

Example 4: This screenshot is of an ad being run by the Chilean Embarazo Inesperado CAM, about which Facebook provides very little information despite the political nature of the ad.

Example 6: This ad screenshot shows how little information Facebook makes available about who is being targeted with the ad and who is behind the Facebook page.

Due to Facebook’s limited implementation and piecemeal enforcement, many countries are left without any transparency as to what ads are being run by opposition groups, who they are targeting, and what they are saying on Facebook and other Facebook-owned platforms. Oftentimes it is up to journalists to uncover such ads or other methods of spreading misleading health information.

For example with regards to WhatsApp, following the legislative debate to legalise abortion in Argentina in 2018, it was reported that opposition groups began a campaign on the app against comprehensive sex education. The campaign, which was reportedly launched by evangelical groups in the country, circulated messages in WhatsApp groups for mothers. The messages went viral and were widely shared. It was reported that the circulated audio messages detailed vulgar and false descriptions of what sex ed classes contain. The messages also were reportedly transphobic. It was reported that similar false information was circulated on Facebook.

Ingrid Beck, a journalist based in Argentina told the Argentine organisation Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género (ELA), with which PI worked on this report that, “The main network to distribute false information is WhatsApp. Followed by the rest of the social media. The list would be WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter. Essentially, they [the opposition] use [social media] to raise doubts and false information about human rights defenders, spread anti-science discourse, anti-scientific evidence, and conservative and reactionary discourse. I think that all those messages come from false news that have no scientific sources or simply fake news that could not even be credible, but as they get replies or are distributed, they become credible. Sometimes they are built in a way that looks like they are real and other times they are absolutely crazy, but because they work with the confirmation bias they make that news credible”.

During the 2018 abortion referendum in Ireland, Facebook “mistakenly launched” a transparency tool that allowed users to see “the real-life location of people who were managing” Facebook pages related to the referendum. A reportedly “significant proportion” of posts related to the referendum were “from pages managed partly or entirely outside of Ireland”. Some of the pages running ads against legalising abortion had foreign page managers including managers based in the UK, Hungary, and “other unidentified countries”. Facebook eventually banned foreign ads related to the referendum. Google eventually banned all ads related to the referendum.

In late 2019, over a year after the referendum, Facebook released data related to how much money was spent to buy Facebook ads related to the Irish referendum prior to Facebook banning foreign ads. It was reported that over €1 million euros was spent, by 350 groups. Facebook has apparently not released information about what groups bought ads, meaning that it is not currently possible to understand how opposition groups, neither foreign nor domestic, targeted people with potentially misleading ads during the referendum.

While Facebook has since taken further steps to increase transparency for users and researchers around what advertisers are buying ads, whom they are targeting, and what they are saying, in many countries, advertisers are not mandated by Facebook to provide heightened transparency about who is behind a message. Given the prominence of the debate around political ads transparency in some countries, it’s unacceptable that Facebook allows such a stark transparency differential. Opposition groups are using Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and other platforms, as the above examples demonstrate, to promote misleading health information and delay people from seeking care. People everywhere should be able to understand why they are seeing an ad and who’s behind it, and societies globally must be able to understand when misleading health information is being promulgated on social media. The effect that misleading health information could have on people’s lives could have devastating results.

Damián Levy, a doctor and member of the Advocacy Committee of the Access to Safe Abortion Network Argentina (REDAAS) told the Argentina-based organisation Equipo Latinoamericano de Justicia y Género (ELA) that “In Argentina, phone calls, websites, Facebook, and WhatsApp are the main forms of technology used in the provision or restriction of reproductive health services and information.” Given this, it’s crucial that Facebook provide meaningful transparency about what organisations are behind anti-reproductive rights ads globally and who they are targeting.

Google and Google-owned YouTube

In the US, Google has come under criticism for giving “tens of thousands of dollars in free advertising” to an anti-contraceptive and anti-abortion network of crisis pregnancy centres.

Groups exist to help opposition organisations promote their services and assist them in applying for Google grants. For example, Heartbeat International’s Extend Web Services offers assistance to crisis pregnancy centres for obtaining Google’s AdWords Grant for Non-Profits.

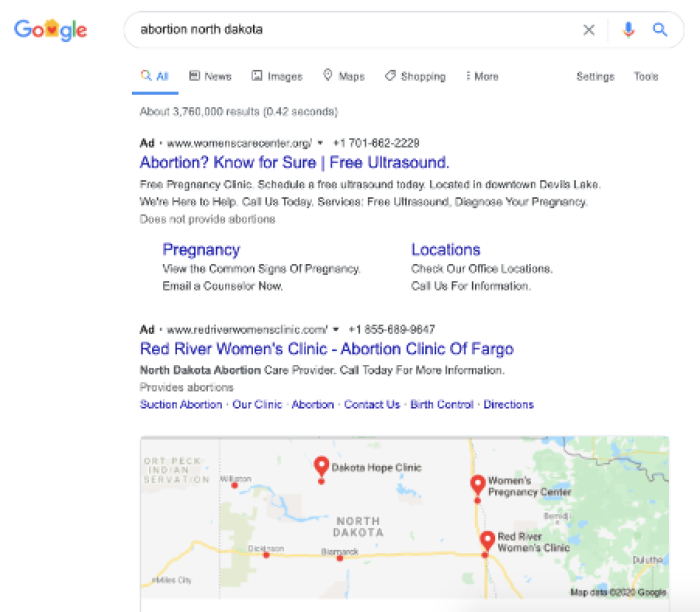

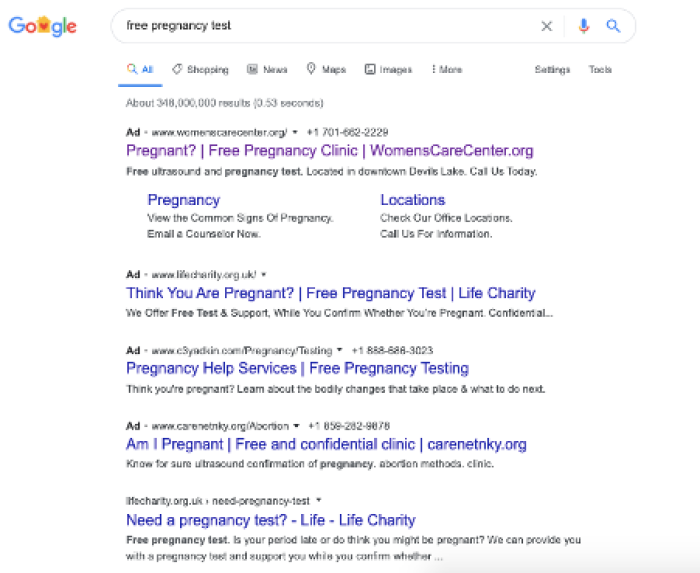

Below are some examples of Google ads running on search terms such as “free pregnancy test” and “abortion”.

In the US state of North Dakota, there is one remaining abortion clinic, the Red River Women’s Clinic. However, Google Maps doesn’t clearly identify which clinic is real and which are crisis pregnancy centres. People searching for abortion care would find it difficult to know which clinic are real. The top ad is a crisis pregnancy centre as well.

All of these ads link to crisis pregnancy centres. The UK’s Life Charity does not promote or refer for abortion.

It’s near impossible to get a sense how opposition groups are advertising on Twitter, due to the nature of Twitter’s advertising transparency tools. The platform launched its political ads transparency tool in 2018, which archived ads related to an election for seven days and gave heighted information about who was being targeted with the ads and who was paying for them. Twitter also retains non-political ads for seven days, before they are deleted from the archive. In 2019 the platform announced it would ban political ads on its platform, meaning that the heightened transparency around election ads was halted. Crucial to reemphasise, for Twitter users outside of the US the company’s definition of political ads was limited to ads tied to an election, instead of ads that were also related to political issues. This means that ads tied to abortion, a highly political issue, would have been allowed to run without heightened transparency.

The company appears to still retain non-political ads for seven days, before they are deleted from the archive. However, the tool is cumbersome to navigate. Ads are searchable only by advertiser, rather than by topic – so to understand what ads are being run that relate to contraception or abortion, a person cannot conduct a global search on the term “abortion reversal”, for example, but instead needs to have an idea of what Twitter users might be running ads, and then individually search for that advertiser to check. Furthermore, ads are deleted after seven days, making it virtually impossible to get a sense of how opposition groups are testing and targeting messages on Twitter.

There have been instances where the platform has removed or rejected opposition ads. In 2017, the platform rejected ads from two prominent opposition groups for violating its “health and pharmaceutical products and services policy”. As of 2020, one of the opposition groups is no longer eligible to run ads on the platform.

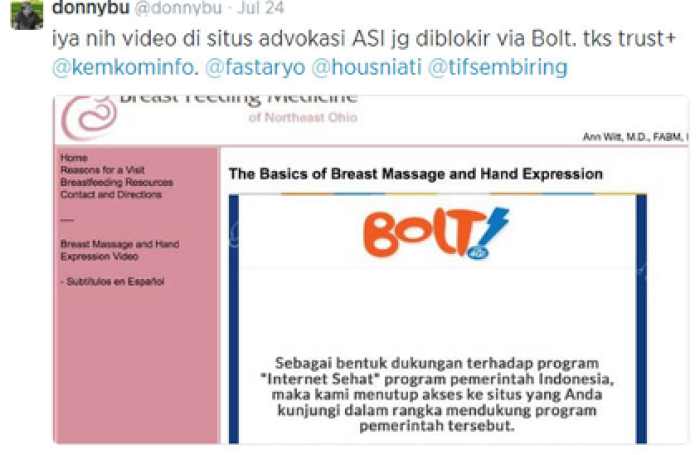

Blocking access to reproductive health information