Country case-study: sexual and reproductive rights in Indonesia

This country case-study was informed by research carried out by the Institute for Policy Research and Advocacy (Elsam).

- Abortion is illegal, except for two exceptions - in the case of a medical emergency, where the woman also has permission from her husband or family, or in the case of pregnancy due to rape

- Access to a range of modern contraception is very limited

- The Indonesian Government has imposed a blocking and filtering method toward the internet that hampers the full enjoyment of human rights.

- Many public institutions such as governmental boards or schools are afraid to provide comprehensive reproductive health education for youth

- Stigma and discrimination are some of the big problems in giving access to non-biased medical reproductive health information in Indonesia

1. What are the barriers to access safe and legal abortion care?

2. What are the barriers to access basic contraception?

3. What are the hurdles in accessing non-biased medical reproductive health information?

4. What are the concerns regarding the use of technology by anti-reproductive rights organisations?

5. What foreign organisations have a large anti-reproductive rights presence?

This research was commissioned as part of Privacy International’s global research into data exploitative technologies used to curtail women’s access to reproductive rights.

Read about Privacy International’s Reproductive Rights and Privacy Project here and our research findings here.

1. What are the barriers to access safe and legal abortion care?

Legal barriers

To identify the barriers experienced by women to access safe and legal abortion care, we have to understand the legal picture. In Indonesian regulation, abortion is illegal, with exceptions for only two reasons[1]:

(1) where doctors can prove that there are indications of a medical emergency, meaning that abortion is inevitably needed to save the mother’s life, this must be accompanied with the woman's husband or family's permission

(2) pregnancy due to rape that results in psychological trauma to the woman

Based on the Law on Health, all acts of abortions without those reasons can be punished to a maximum of ten years in jail or a fine of IDR 1 billion. Both the medical professionals that provide the abortion and the woman who obtained it can be punished.

This criminal sanction states:

“Every individual who intentionally commits abortion not in accordance with provisions as referred to in Article 72 subsection (2) shall be penalised with imprisonment at the longest 10 (ten) years and a fine of at the most Rp 1,000,000,000 (one billion rupiahs).[2]

A more technical provision is in the Ministry of Health Regulation No. 3/2016 on the Abortion Services. This regulation requires women that intend to get an abortion because of rape obtain a letter from a doctor and a letter from the investigator, psychologist, and/or related expert about the event of the rape. The letter is given to the woman after she is examined by the abortion eligibility team, which consists of doctors that have a certification to perform an abortion. The doctor will provide her with a letter confirming the gestational age. Meanwhile, the statement from the investigator and/or psychologist is obtained by a different process as regulated in Indonesian procedural law.

The Ministry of Health Regulation also says that a person who obtains an abortion cannot get the service from the same doctors for a different reason, except if there are not enough doctors in the area. For example, if doctors have provided a woman with abortion care for pregnancy due to rape, the same woman can not have access to abortion care from the same doctors for a medical emergency.

In terms of abortion because of a medical emergency, a woman has to obtain the husband’s permission. The regulation does not describe in what form the consent should be given, but usually, the facility will provide a standard letter of statement for the husband to sign. If there is no husband’s permission, the permission should be given by the family. That means unmarried women can access the facility as long as there is permission given by her family and for the reasons that regulation has determined in advance.

The Law on Health establishes a gestational age limit of six weeks after which doctors are not allowed to provide abortion care services, except for medical emergencies. Meanwhile, the Government Regulation No. 61/2014 on the Reproductive Health regulates a maximum of exactly 40 days of pregnancy for a victim of rape to be able to obtain an abortion. It implies the doctors may provide an abortion after six weeks, if they think it is the only way to save the mother’s life if the examination shows the indications of a medical emergency.

These indications are determined by two categories:

(1) the pregnancy threatens the mother’s life and health;

and/or

(2) the pregnancy threatens the fetus’ life and health, including if it suffers from severe genetic or congenital issues that would make it difficult for the fetus to live outside the womb.

This provision could mean that a victim of rape can obtain abortion care no matter the gestational age. However, it is not clearly stated in either the government regulation or the Ministry of Health regulation. It is also not clearly stated whether or not the doctor’s statement for a victim of rape may also contain information regarding medical condition.

Furthermore, the Articles 346-349 of the Indonesian Penal Code places sanctions ranging from four years to 15 years in prison for an illegal abortion. If an illegal abortion is performed by a doctor, a midwife, or a pharmacist, the sentence may be extended by a third and their permit to perform related activities may be revoked.

Currently, the Government and the House of Representative are discussing the new Bill of Penal Code that will potentially criminalize broader individuals actions, meaning only official medical professionals or other trained professionals can demonstrate and provide a means of preventing pregnancy. Anyone other than that, including civil society organizations, will potentially be sanctioned.

Access to unsafe abortion care

With all of these circumstances, it could be argued that many women in Indonesia prefer to access unsafe and "illegal" abortion care. This is because of various factors, from a fear of legal sanctions to culture or "social values".

One article[3] shows that as many as 66% of married women have abortions due to already having enough children. Other women decided (based on other research) to have abortions due to physical considerations and to ensure they could continue higher education. However, since abortion is seen by many as against religious teachings, many women prefer to access unsafe and illegal abortion care to avoid stigma, even though it is expensive. For example, illicit clinics provide abortion services for IDR 3 to 4 million for a pregnancy under eight weeks.

According to Indonesian law all abortion care should be delivered directly by doctors in the official health facility. Article 349 of the Indonesian Penal Code implicitly indicates that Indonesian law prohibits a person from having an abortion by taking abortion pills. Therefore, healthcare professionals who are not doctors, such as pharmacists, can be prosecuted for helping a person to have an abortion. This article[4] states that abortion drugs can only be provided by the physician for inpatients with strict supervision. It means a person cannot lawafully procure themselves abortion pills in stores. That is why many online or offline stores sell abortion drugs illegally, meaning the seller can be prosecuted by law[5].

In cases of pregnancy due to rape, abortion is an almost impracticable choice because of the difficulties faced by women in the process, not to mention social stigma against the victim. One news article[6] describes a story of a woman that was scared to have an abortion after she had been raped by her partner. When her pregnancy reached seven months, her partner gave her a pill that resulted in a miscarriage. Coerced by her partner, she buried the fetus’ body by herself and ended up facing legal sanction. Later, she was released by a higher court. Furhter information regarding the prosecution of illegal abortion can be read in the found in the footnotes[7].

It is hard to access safe abortion care in the case of pregnancy due to rape, because of the process required by Government Regulation No. 61/2014 on the Reproductive Health and Criminal Procedure Law. According to the former, the victim must provide a lot of documents before recieving lawful abortion care, such as a written statement of pregnancy due to rape from a doctor, and a dcument from the either an investigator, psychologist, and/or other related experts attesting to the event of rape (Art. 34[2]). The victim has to obtain both to have an abortion. In many cases, the woman who has been raped is vulnerable in the face of the law. The social stigma existing against both unmarried pregnant women and pregnant victims of rape often leads them to have a self-abortion (taking pills or herbs, etc.) or to go to either an illegal clinic or, mostly, a shaman.

Religion

An article[8] appears to reflect the opposition arguments that abortion should not be legal for the sake of child protection and religious values. Religious values are considered the most popular justification against abortion care for most of the Indonesian people, as shown by this article[9]. Abortion is viewed as equivalent to killing a living creature. A fetus is a living creature, at least from the Islamic perspective. According to this religious belief, abortion should be prohibited for any reason. Relying on the hadith and verses from Qur’an, the Islamic view appears to be that abortion might be undertaken before four months of pregnancy. Abortion conducted to save a mother (which means a married woman) is still permissible only if the severity of the mother’s health condition can be proven and keeping the fetus will harm the mother’s life. Meanwhile, for a victim of rape, there is a consensus within most of the ulama that abortion should be a sin and with no room for exceptionality.

As a legal notion, the Indonesian law seems to confuse the term of “safe abortion” with a “legal abortion”, which makes it harder for women, especially victims of rape, to access safe abortion care. Only appointed health facilities that can lawfully perform an abortion.

Some organizations, such as Women on Web (Indonesian Branch), provide online consultations to help women having a medical abortion. Yet, this is only accessible for women that live in the city or an area where the internet access/infrastructure is moderately good. Many women seek pills via the internet without the help or advice of a doctor. Some of them are using traditional methods believed to trigger a miscarriage, such as by consuming a particular fruit like pineapple or herbs, hard jumping, etc.

These traditional methods are relatively common, more so than medical abortion, given the fear of stigma or judgement, or fear of side effects from the pills. Medical abortion is also not without challenges, as many medical professionals are cynical about medical abortion and mistakenly advise women to go to the legal clinic to have an abortion. It is because many medical professionals still believe that it is unsafe for women to take the doctor prescribed-pills and instead suggest a legal clinic is the only choice for safe abortion care.

As mentioned above, some organizations have provided online consultations for women to access medical abortions in particular. Official state institutions have not deployed similar platforms. This is in line with the law, which only allows abortion care to be provided by appointed health facilities.

The Ministry of Health can appoint a healthcare facility pursuant to a decision made by regional health services across the country. The medical professionals have to obtain a training certificate to be able to perform an abortion in the facility. One article[10] mentions that the currently existing regulations are not optimally implemented, especially for women who are pregnant due to rape. Those a significant number of the health services and professionals are prepared and certified mostly to provide abortion care for a woman facing a medical emergency, they are rarely aware of how to provide support or care to victims of rape.Medical professionals are also reluctant to provide abortion services for victims of rape as they believe it will contradict their Hippocratic Oath.

The gestational age is likewise a problem since many victims do not realize they are pregnant within the given timeframe, denying them access to safe and legal abortion care.

Furthermore, other problems arise from the Ministry of Health Regulation No. 3/2016 since the Government has not been transparent regarding legal abortion services as regulated both in the Ministry Regulation or in the Law on Health. This article[11] shows that it is tough to find medically standardized abortion services, as the Government has not established the list of authorised health facilities yet.

Heni Widyaningrum, who works for Perkumpulan Keluarga Berencana Indonesia (PKBI), explains in an interview that the term 'indications of medical emergencies' is also problematic since it focuses solely on physical emergencies, neglecting economic and psychological reasons as well. Both the Ministry of Health Regulation and the Government Regulation do not establish a clear standard of the medical emergencies required to meet the standard for a lawful abortion, which later creates confusion among doctors on how to establish the criteria for such emergencies. Thus, doctors have interpreted the law inconsistently and operated with different standards.

2. What are the barriers to access basic contraception?

Indonesian law strictly regulates the use of contraception for people. In fact, certain contraception devices such as condoms can be easily obtained by everyone in stores. The use of contraception is linked to the family planning policy that is regulated in the Population and Family Development Law 52/2009. The law states that contraception services should be provided by medical professionals or other trained professionals in accordance with religion, cultural norm, ethics, and health (Art. 24 and Art. 28). While we can still find condoms in stores, medical contraception or other contraception devices are required to be provided directly by the professionals mentioned above in order to implement a family planning program. The Population and Family Development Law also states that contraception services are among they responsibilities of both central government and local government. The prohibition is often carried out by local governments such as Surabaya[12], Luwu[13], Makassar[14], and many others. The prohibitions are often established in the form of circular letters or appeal for the stores or sellers.

The implementation of contraception services is largely governed by the Ministry of Health Regulation Number 97/2017 regarding the health services prior to pregnancy, during pregnancy, labour, after delivery, contraception and sexual health services. This regulation is aimed strictly at married couples. This is apparent from Article 18 (and Article 22 as well), which states that contraception services should be given responsibly considering the religious value and cultural norms in addition to health. The same article also states that medical facilities or other facilities should offer short-term contraception methods such as by pills and condoms.

The Indonesian Penal Code Article 534 states that any act of exhibiting means of preventing pregnancy is a punishable act with maximum light imprisonment of two months or a maximum fine of two hundred rupiahs. This article is not engaged if such acts are undertaken by an authorized medical professional to implement a family planning program. However, this article has not practically been since the 1990s because of the government’s family planning program[15]. The new bill of penal code attempts to revive a similar article and has triggered public outcry especially from civil society organizations.

This legal framework has made access to a range of modern contraception very limited. While condom can still be found in stores, any other contraceptive devices have to be given by the medical professionals directly. People can still seek pills in the marketplace, however they do so at their own risk and without a doctor informing them of the potential impact on their health. Even where contraception is commercially available, some individuals are dissuaded due to fear of stigma or embarrassment.

3. What are the hurdles in accessing non-biased medical reproductive health information?

In respect to non-biased medical reproductive health information, familiar Indonesian people tend to see this matter in a binary manner depending on whether the person is married or unmarried. Commonly, many medical professionals will ask about marital status when a woman seeks to access certain information during their consultation with a doctor. In some instances, a discussion may ensue whereby women are told that they should be married, for example, to be able to access contraception or even to get information about STDs or HIV.

This following article[16] is a clear example of how medical professionals' personal beliefs may come to influence their role as objective advisors. An unmarried woman experienced health issues after taking abortion pills by herself. Instead of giving her the information she needed, the medical professional asked about her marital status. This common practice deters individuals from seeking appropriate information from an expert and instead encourages many individuals to seek information on the internet where misinformation is prevalent.

According to the said article, Tina (not a real name, 26 y.o) experienced bleeding after taking an emergency contraceptive pill (morning pill) in 2017. Tina said she went to the hospital in Slipi a week after because her bleeding did not stop. In the registration desk, she met with the nurse and explained her situation. The nurse then responded by asking her about her marital status three times.

Below is the dialogue between Tina and the nurse as written in the article:

“Have you married, Miss?” asked the nurse.

“Not yet. Just write what my ID says.” Tina replied.

“Have you had sex?” the nurse then asked her again.

“I have.” Tina replied.

The article then said that the nurse’s facial expression changed for having heard the answer and asked Tina, “Pardon me, have you married?”

Tina replied to the nurse’s question and the nurse again raised the issue of marital status, “Haven’t married yet but you have had sex?”

Tina replied angrily, “I haven’t married but why did you ask me the same question again?”

The nurse stated that she required that marital information for the examination, but that wasn't true. Tina eventually met the doctor only to hear them say: “You better get married very soon, Miss, because this (bleeding) is caused by you having been stressed out.”

The article then goes with another story from Putri (not a real name, 28 y.o). Three years ago, Putri had heard about the death of an Indonesian celebrity from cervical cancer, which encouraged her to go to the nearby health facility to get a pap smear. From the information she got, she knew that this service was guaranteed by the BPJS Kesehatan (Indonesian national health insurance). From the health facility she went to, Putri should have easily obtained a referral for her to access the service in the clinic. Unfortunately, the clinic refused to have the pap smear service covered by the BPJS Kesehatan. Putri said in the article about her experience, “The nurse said that BPJS Kesehatan regulation had annulled the pap smear service for unmarried sexually active people.” This article confirms[17] the nurse's statement.

Tina said in the previous article that she also experienced a similar reaction when she wanted to get an IUD. The nurse kept asking her about the marital status, her marriage age, and so on. Instead of telling the nurse that she had not married yet, she told the doctor that she had just gotten married a year ago and wanted to get contraception because of work. The doctor reportedly told her, “You just got married a year ago and now wanted to get contraception, if you are always busy at work, when will you get a child?” This experience made Tina feel uncomfortable about accessing a contraception service from a governmental clinic and pushed her to go to the private clinic instead. It is worth noting that this option is not available to all women, and that prejudice among healthcare professionals may have perverse consequences on women of lower means.

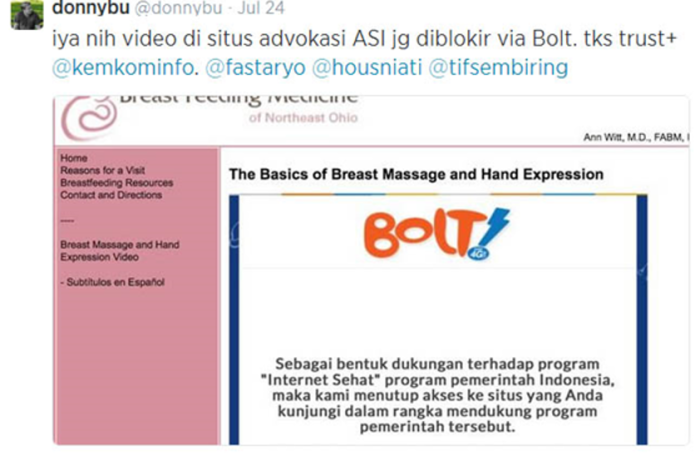

Blocking and Filtering Policy: Government that is too sensitive

The Indonesian Government has imposed a blocking and filtering policy toward the internet that hampers the full enjoyment of human rights. It is regulated in the Ministerial Regulation No. 19/2014 on Negative Contents on the Internet (Penanganan Situs Bermuatan Negatif) through which the Ministry of Communication and Informatics established a database system called Trust+Positif under the large-scale government campaign program named “Internet Sehat” (Healthy Internet). The Trust+Positif is a list of blacklisted internet content that the Ministry considers to be negative content.

According to the Ministry Regulation, the negative content consists of pornographic material and other illegal material as regulated in the Laws (undang-undang) which ranges from gambling, fraud, child abuse, defamation, violation of intellectual property rights, etc. Based on an individual or institutional report or ministerial investigation, the Ministry will filter the negative contents using URL/Domain/Keyword based filtering to establish whether or not it should remain available online. If the Ministry considers the content is negative, it will have an authority to order ISPs to block the content so that people can no longer access it. This method sometimes will not only block one URL but also a whole website. The keyword-filtering method will block the domain so that the entire site can not be accessed. Currently, based on the manual checking in the website, the Ministry has enlisted as many as 1.138.598 domains in the blacklist.

Elsam[18] has studied the Indonesian internet content policy and accounted several problems, including the following:

(1) an over-inclusive and general definition of what is defined as negative content;

(2) the Ministry of Communication and Informatics' broad powers to sanction ISPs that refuse the minister’s order to block the contents in question; the order itself is also made with an absence of due process;

(3) limited participation from civil society organizations enables decisions being made to serve the majority’s value-system; and

(4) the blocking and filtering method is often wrongfully targeted and many non-negative pages have been blocked (such as breastfeeding education websites, LGBTQIA websites, etc.).

Amalia, who works for the Indonesian branch of Women on Web, explained that the website had been blocked several times for posting an article about medical abortion. The decision made by the ministry was vague due to the absence of the ministerial assessment/investigation result and sometimes was carried out without prior notification. As happened with one of the Women on Web articles, Amalia said that she made a report and the ministry replied with cursory information about the blocking decision.

The Women on Web in Indonesia made a report and inquiry to find out what the reason was for its website being blocked and demanded the government revoke the blocking decision. The reply from the ministry administrator was:

“We wanted to inform you that your site has been blocked for posting an article or activity related to abortion. Normalization process has been undertaken after we conducted a verification confirming the removal of negative contents posted in womenonweb.org.”

The process of deciding whether or not particular content is negative has been odd and unclear. This is unsuprising, given that the Trust+Positif database itself was actually built long before the formulation of the Ministerial Regulation 19/2014.

The database has been in effect since 2011 following the Circular Letter of the Ministry of Communication and Informatics Number 1598 of 2010 on the Compliance to the Laws Regarding Pornography that refers to some laws including Telecommunication Law (36/1999) Article 21, Electronic Transaction and Information Law (11/2008) Article 27(1) and Pornography Law (44/2008) Article 4(1) and Article, all of which relate to "indecency". The Trust+Positif database came to be after the circular letter mentioned above was issued.

In 2015, the Ministry established a multi-stakeholder forum through the Ministry Decision Number 290/2015 on Handling Internet Negative Sites as a recommending forum for the ministry to catogorise internet content as negative. The forum consisted of four chambers including pornography, violence against child, and internet security chamber; terrorism and ethnicity, religion and race chamber; illegal investment, fraud, gambling, drugs, and food chamber; and intellectual property chamber. This forum finished its work on 31 December in the same year and was never reformulated. The Ministry has never informed the public of how it carried out the assessment nor the criteria on the basis of which many decisions were made using.

The government’s sensitivity to some issues around reproductive health has impacted the full enjoyment of people's rights. Trust+Positif is only one of the setbacks created by the government that affects how people get information regarding medical reproductive health. The WOW’s experience is an indicator of how the government percieves the internet, as well as the issue of abortion care, so that people could not get clear information on how to access abortion services.

As previously discussed, many medical professionals see medical abortion as something unsafe and unjustified for women to have - meaning it is tough for individuals to access clear information related to it, even on the internet. Besides, abortion care is still considered fundamentally illegal, as not everyone may access it. This perspective seems to affect the internet content policy, making the proliferation of responsible information and transparency even harder. It places women in a vulnerable condition as it will lead them to seek unsafe abortion services, either online (such as the marketplace) or offline (illegal clinic or risky advice from the amateurs).

Apart from the ambiguous internet content policy, public institutions have also shown reluctance in adopting the complete picture of reproductive health information for as broad audiences as possible to understand. Heni, in the interview, says that her organization had attempted to introduce such issues to the Ministry of Education and Culture hoping that reproductive health rights could be taught by teachers in a range of subjects in Indonesian’s schools. This idea was initially rejected, subsequently included as a part of materials for the school counsellors. Both the CSO and the Ministry have conducted many pieces of training sessions for the counsellors. Still, not all issues have been accommodated in training, such as abortion care or contraception for unmarried people. Tunggal Prawesti from Hivos has also confirmed this problem in the interview - that many public institutions such as public schools censor information around some issues such as safe abortion or contraception.

Research conducted by Pakati and Kartikawati in 2013[19] showed the extent to which reproductive health information had been adopted in 23 schools in 8 regions across Indonesia. The research shows that reproductive health is partly given in several subjects, including biologi, pendidikan jasmani, kesehatan dan olahraga (biology, physical, health and sports education), and religion.

Only one school provides its students with a regular subject regarding reproductive health. The information is also given in extracurricular activity or in seminars or workshops. Materials covered are mostly related to reproductive organs, physical and nonphysical change in puberty, and HIV and AIDS. Meanwhile, fewer materials are provided around dating violence, contraception tools and unsafe abortion. The research describes that these topics are not addressed by the school because it is afraid of being seen as allowing the students to date. Many teachers or stakeholders interviewed as shown in the research stated the importance of reproductive health education but such information, they said, should be given sparsely.

As cited from the interview in the research, a key resource who works for the Education Board in Lampung said:

“The knowledge on reproductive health should be given to adolescents thoroughly. Otherwise, this subject would be a source for them to free sex.”

2. Indonesian’s Reproductive Health Policy: The ‘Importance’ of Cultural and Religious Values

The fact that many public institutions such as governmental boards or schools are afraid to provide comprehensive reproductive health education for youth can be analysed from the way this issue is regulated in the policies. Many reproductive health regulations reflect the cultural as well as the religious way of thinking, which makes it harder for people to look at the issue from an objective perspective. There are two laws that need to be analysed here, namely the Law on Health No. 36/2009 and the Law on Population and Family Development No. 52/2009.

2.a. The Law on Health No. 36/2009

This law defines reproductive health as “the wholly healthy condition whether physically, mentally, and socially, not merely free from diseases or disabilities relating to the reproductive system, function and processes in men and women.” (Art. 71). It is the absolute definition as accepted by the WHO. In a similar article, reproductive health is included (a) prior to pregnancy, during pregnancy, childbirth and post-natal; (b) pregnancy management, contraceptive devices and sexual health; and (c) health of the reproductive system[20]. However, the rights enshrined in Article 72 exhibit some problems. One of the rights is that every individual is entitled to have a healthy and safe reproductive and sexual life freed from coercion or violence from their lawful partner. This provision implies that only a sub-section of Indonesians may enjoy the rights contained in the law. The law itself does not provide any further explanation of what it meant by “lawful partner”, but the meaning can be derived from the Indonesian government's emphasis on marriage, as regulated in the Law on Marriage No. 1/1974. Other rights such as the right to determine the rights mentioned above and the freedom to reproduce are limited to what the law calls it as “nilai-nilai leluhur” (noble values) and religious norm. The law also emphasizes that reproductive health services (including abortion services) be provided while respecting religious values.

The Indonesian government has enacted a special regulation to implement reproductive health provisions in the Law on Health. Through the Government Regulation No. 61/2014 on Reproductive Health, the government attempts to assert its way of thinking toward reproductive health services. The scope of the regulation includes health services for the mother, abortion due to indications of medical emergencies and rape, and reproduction with aid or pregnancy with an unnatural way (kehamilan di luar cara alamiah).

The Regulation also contains provisions on reproductive health services for adolescents. Interestingly, this service for adolescents is provided to prepare them as a parent. Article 11 describes the aim of the services is to enable the adolescent to have more “healthy and responsible reproductive health.” In the explanatory notes, this phrase is said to include every aspect in to preparing the adolescent physically, psychologically, and socially, to marry and to get pregnant at a mature age. And again, the services are provided for the adolescent while respecting religious values.

2.b. The Law on Population and Family Development No. 52/2009

This law has become the basis of the National Population and Family Planning Board’s operation in managing the family planning and population control program in Indonesia. The law establishes reproductive health as a part of the family planning policy, which focuses mainly on improving quality and access of information, education, counselling and services. The law recognizes the right to reproduce, and includes the right to obtain information, protection, and help in accordance with social ethics and religious norms.

3. Listen to Your Parents!

Cultural and religious reasons seem to compound each other when it comes to the impartiality of information towards reproductive health. Parents play an indavertently central role in passing misinformation down to younger generations, often influenced by conservative and traditional approaches to reproductive health. For young Indonesian generations, parents or older people are considered as an essential resource to get information, and failure to abide by it is considered unacceptable. This means more inaccurate information persists.

Riska Carolina, who works for Persatuan Keluarga Berencana Indonesia, said in a focuse group discussion that parents are difficult to convince when it comes to comprehensive reproductive health information. She said:

“Based on our research, parents hold important rules in deploying the information to their children. Parents, especially fathers, decide what their children should do in managing their reproductive health. Sometimes young people ask their friends too but will come back to their parents to validate the information”.

While parents living in an urban area are relatively knowledgable due to better access to digital technology, parents in rural areas are less able to rely on devices to obtain necessary information regarding reproductive health. Young people will get some information from social media but will eventually talk to their parents about events such as menstruation.

4. Access to the Digital Devices: Infrastructure and Literacy

Digital infrastructure has a vital role in deploying reproductive health information. Indonesian AIDS Coalition (IAC)’s representative said in the focus group discussion that three things affect the distribution of HIV/AIDS information: regional infrastructure, age, and level of education. APJII’s survey states that Java island contributes to a total of 55.7% out of total internet users while Sumatera is second accounting for 21.6% out of total internet users across Indonesia[21].

As many as 171,17 million people have used the internet in 2019 where 16.7% of total users live in West Java, and 14.3% as well as 13.5% of total users inhabit Central Java and East Java, respectively. Bali and Nusa Tenggara have the least users accounting for only 5.2% of the total users while Kalimantan accounts for 6.6% of total users and Sulawesi and Papua combined have an estimated 10.9%. The gap in digital infrastructure is an old problem the government has traditionally attempted to tackle, for example, by establishing the Palapa Ring Project. The Internet has connected more people around Java and Sumatera, enabling flows of information, while the eastern part of Indonesia like Papua and Sulawesi still struggle to connect.

Age is also a factor that influences the level of understanding. Millennials and younger people are easier to appraise of up-to-date information while the older population is not. APJII’s survey shows that the population in the age range of 10-39 years old accounts for more than 60% out of the total internet users. IAC’s representative also says that the more educated a person, the more accessible for the individual to understand the information compared to individuals that have less education. The level of education also determines the accessibility to digital devices.

5. Stigma

Stigma and discrimination are becoming one of the big cliffs to achieve non-biased medical reproductive health in Indonesia. In particularly for the young generation, and those within it who are single. Stigma for women who access modern contraception such as condoms, for instance, easily labelled as sex workers. Men have their sexual orientation questioned upon asking about reproductive health information.

The presence of technology alleviates the boundaries, yet as mentioned before, internet access, as well as literacy, is a privilege and not accessible for all. In some cases, reproductive health activists in Indonesia also mention the absence of privacy protection in Indonesia as a key factor behind the low number of people accessing the reproduction health information[22]. Some men admit they have to make some alternative accounts on social media to be able to access reproduction health information freely without any judgment.

The absence of reproductive health information is also experienced by the transgender community. In Indonesia, transgender communities are still facing structural discrimination in particular to access the identity card. Hence, some transgender people are unable to access the fundamental rights services, including health or reproductive services. The big obstacles emerge in particular for those who have done hormonal treatments or surgery. Exclusion from access to basic services enables misconceptions to persist in relation to hormonal treatment or surgery. For instance, some communities still believe transwomen who have had surgery are capable of menstruation.

4. How is the use of technology influencing the reproductive rights space?

A few religion-based organizations have developed websites and campaigns on social media to provide knowledge and information against feminist perspectives as well as disseminating misinformation about reproductive health, efforts notably aimed at women.

We found nothing publicly available about sharing medical data or inappropriate collection.

5. What foreign organisations have a large anti-reproductive rights presence?

There is no foreign organization identified to operate in campaigning against reproductive rights in Indonesia.

1. Stated by Art. 75 of Law No. 36/2009 on Health

2. Art. 194

3. Abdul Hadi. Mempertanyakan Kembali Kebijakan Aborsi di Indonesia. Ekspresi Online. February 07, 2019, https://ekspresionline.com/2019/02/07/mempertanyakan-kembali-kebijakan-aborsi-di-indonesia/

4. Dini Pramita. Lika-Liku Transaksi Obat Aborsi, Majalah Tempo, January 18, 2020, https://majalah.tempo.co/read/kesehatan/159446/lika-liku-transaksi-obat-aborsi?hidden=login.

5. These are examples of the related cases where the drug selles are arrested by the police: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2019/03/14/five-busted-in-klaten-for-allegedly-running-online-abortion-clinic.html; https://www.merdeka.com/peristiwa/penjual-dan-pembeli-obat-aborsi-di-malang-ditangkap-polisi.html (both the drug seller and the buyer are arrested by the police in Malang); https://regional.kompas.com/read/2020/02/18/21031171/jual-obat-penggugur-kandungan-penjual-obat-kuat-di-madiun-ditangkap (the abortion drugs seller is arrested by the police in Madiun).

6. Aditya Widya Putri. “Aborsi Masih Tabu Hukum Indonesia Membatasinya Secara Ketat,” Tirto.id, February 27, 2019, [https://tirto.id/aborsi-masih-tabu-hukum-indonesia-membatasinya-secara-ketat-dhMS]

7. Agence France-Presse. “Indonesia Girl Jailed for Abortion After Being Raped by Brother,” The Guardian, July 21, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/21/indonesia-girl-jailed-for-abortion-after-being-raped-by-brother, there is no official record regarding the number of people being prosecuted for illegal abortion. There is only a few number of cases of rape victim being put in jail for abortion, but not recorded very well.

8.Rosalind Angel Fanggi. “Kebijakan Kriminalisasi Pengguguran Kandungan Dalam Pembaruan Hukum Pidana Indonesia,” [https://media.neliti.com/media/publications/109758-ID-kebijakan-kriminalisasi-pengguguran-kand.pdf]

9.Pusat Kajian Fikih dan Ilmu-Ilmu Keislaman. “Hukum Aborsi Dalam Islam,” PUSKAFI. July 23, 2018, https://www.ahmadzain.com/read/karya-tulis/258/hukum-aborsi-dalam-islam/

12. https://regional.kompas.com/read/2015/02/17/1702253/Risma.Larang.Minimarket.Jual.Alat.Kontrasepsi.untuk.Pembeli.yang.Belum.Menikah, the Mayor of Surabaya implement a circular letter to prohibit stores from selling condom for unmarried people.

13. https://nasional.tempo.co/read/721720/daerah-ini-larang-penjualan-kondom-di-supermarket/full&view=ok, the local government prohibits stores from selling condoms for unmarried adolescents.

14. https://beritakotamakassar.fajar.co.id/berita/2020/02/14/wajib-perlihatkan-ktp-pembeli-kondom-sepi/, the local government said that people that want to buy condom should show their ID to the seller.

15. Supriyadi Widodo Eddyono, et al, Akses Terhadap Informasi dan Layanan Kontrasepsi dalam Rancangan KUHP, (Jakarta: ICJR, 2016), https://www.dropbox.com/s/xsdr5jltllf6smi/Buku%20Akses%20Terhadap%20Informasi%20Kontrasepsi%20KUHP-23112016.pdf

16. https://tirto.id/diskriminasi-akses-kesehatan-reproduksi-untuk-yang-belum-menikah-es4H

19. D. T. Pakasi, & R. Kartikawati, (2013). Antara kebutuhan dan tabu: pendidikan seksualitas dan kesehatan reproduksi bagi remaja di SMA. Jurnal Makara Seri Kesehatan, 17(2), 79-87. (in English: Between Needs and Taboos: Sexuality and Reproductive Health Education for High School Students)

20. For further reading, please refer to http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/ins160173.pdf.

21. For further reading, check out https://apjii.or.id/survei

22. Statement from representative of Pamflet Indonesia in Online Focused Group Discussion, 3rd April 2020.