Country case-study: sexual and reproductive rights in Kenya

This country case-study was informed by research carried out by KELIN.

- Despite the legality of abortion care in a range of circumstances, public awareness remains low

- Foreign influences play a significant role in Kenya, ranging from development aid funding to opposition campaigning

- Technology-based tools facilitating access to sexual and reproductive rights are gradually emerging

1. What are the barriers to access safe and legal abortion care?

2. What are the barriers to access basic contraception?

3. What are the hurdles in accessing non-biased medical reproductive health information?

4. How is the use of technology influencing the reproductive rights space?

5. What foreign organisations have a large anti-reproductive rights presence?

This research was commissioned as part of Privacy International’s global research into data exploitative technologies used to curtail women’s access to reproductive rights. Reproductive Rights and Privacy Project. Read about Privacy International’s Reproductive Rights and Privacy Project here and our research findings here.

1. What are the barriers to access safe and legal abortion care?

In Kenya, access to abortion care is restricted by the Constitution, which provides that: “Abortion is not permitted unless, in the opinion of a trained health professional, there is need for emergency treatment, or the life or health of the mother is in danger, or if permitted by any other law”.[1]

Additionally, the Health Act and the Penal Code enable trained healthcare professionals to procure an abortion either in good faith and with reasonable care and skill if in their professional opinion the life and health of the person seeking abortion care is being threatened. The health criterion encompasses a person’s physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Lastly, there are national guidelines on the management of sexual violence in Kenya which entitle victims of sexual violence to terminate a pregnancy. Outside these circumstances, the Penal Code criminalises ‘unlawful abortions’, creating an offence for both women who seek the services and persons that provide the services, the offences carry prisons sentences of up to 14 years.[3]

As a result, a woman qualifies for access to safe and legal abortion care:

- Where there is need for emergency treatment;

- Where the pregnancy constitutes danger to the life of the pregnant woman;

- Where the pregnancy constitutes a danger to the health of the pregnant woman;

- Where the pregnancy is due to sexual violence; or

- Where it is permitted by any other written law.

Uncertainty on the legality of abortion care

Despite what appears to be a straightforward legal position, studies show that one fifth of women in Kenya don’t know if abortion is illegal. This lack of information highlights the first barrier to access to safe abortion services in the country. It is reported that 41 percent of unintended pregnancies in Kenya will end in an abortion, resulting in approximately 500,000 abortions each year. As a result, maternal mortality is high with about 6,000 deaths per year, 17 percent of which are due to complications stemming from unsafe abortion practices. These statistics are primarily due to a lack of information on access to safe abortion and post abortion care as women are not aware of what options may be available to them or the health complications they may be facing should they opt for back-alley abortions.

The secrecy associated with abortions in the country perpetuate the idea that abortion care is an illegal and illicit “back door” activity which often leads to unsafe abortions. This is a direct consequence of health providers not receiving training on how to administer safe abortion care and not knowing whether or not they can legally do so, thereby creating a barrier of access to abortion care services. Despite the release of the Standards and Guidelines on Reducing Maternal Mortality and Morbidity from Unsafe Abortion and training programmes for mid-level providers in 2012, these were abruptly withdrawn in December 2013, with the Ministry of Health issuing a memo stating that there was no need to train health workers on safe abortion care or import drugs for medical abortion care. Though the withdrawal of the guidelines and the memo were successfully challenged in court, the Ministry of Health is yet to fully comply with the ruling. It has also been reported that despite the ruling many Kenyans, including health, practitioners continue to be ignorant about the contents of the Guidelines.

In light of the above, most women remain unaware of the legal exceptions and few healthcare providers trained on the Guidelines. These are crucial as they outline where, how, by whom and under which circumstances an abortion should be performed.

Financial barriers

Socio-economic factors also play a role in the exercise of sexual and reproductive rights. Safe abortion care in clinics is said to cost about 20,000 Kenyan shillings, whereas unsafe abortions are roughly a tenth of that price. It is clear that women from poorer communities will therefore suffer as they cannot afford this and will have no choice but to resort to back-door abortions. The African Population and Health Research Center calculated that in 2012 the Kenyan government spent an estimated US $5.1 million treating women who had developed complications from unsafe abortion in public health facilities, a number that increased to about $6.3 million in 2016. It would probably cost less for the Kenyan government to provide affordable abortion services than it does to treat the complications borne by unsafe abortions in the country.

Lack of private sector organisation funding

In 2018, the United States cut aid to foreign family planning programs which left many women in Kenya without affordable access to contraceptives leading to many resorting to back-door and unsafe abortions. The reduction in funding was due to implementation of the Helms Amendment introduced in 1973 by the US Senator Jesse Helms which prohibited the use of US foreign assistance for safe abortion care and other family planning programs. This foreign policy change acted as a blanket ban for the use of foreign aid funds for abortion care under any circumstances, and affected notable providers of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya such as Marie Stopes International (“MSI”) and Family Health Options Kenya who had to stop offering subsidized contraception and cut a community outreach program.

In addition, the Trump administration restored the Mexico City Policy or ‘Global Gag rule’ which required all non-governmental organisations operating abroad to cease the provision of pregnancy by choice initiatives or risk being denied federal funding. The policy which was intended to reduce the number of abortions instead had the opposite effect. Lack of funding due to the above policies has closed clinics and curtailed family planning and maternal child healthcare services thereby frustrating the affordable access to safe abortion care services.

Increased hostility towards the private sector and civil society from opposition groups

Non-governmental organizations and other private sector organisations also face public scrutiny with respect to abortion and post-abortion care services by opposition groups. Notably, in November 2018, some of MSI reproductive health services were suspended including their abortion care services. This was due to a petition by members of Citizen Go Africa who accused Marie Stopes of advocating for abortions through radio stations which resulted in the Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Board demanding that the organization stop offering abortion care services.

After an audit by the Board confirmed MSI had complied with all laws and regulations, the Kenyan government lifted the suspension of MSI services. But the damage had already been done. Jane Maina, the Executive director of the Trust for Indigenous Culture and Health who campaigned for the ban to be lifted said the suspension of Marie Stopes services had had a chilling effect on women’s health services and voiced concern over what this means for individual healthcare providers. She further asserted that advocates fighting for reproductive rights faced an increasingly hostile climate and opposition groups always hit hard after success in the realisation of progressive reproductive health services for women in Kenya. For example, last year opposition activists put up billboards shaming women seeking to undergo abortion services. This was met with women’s rights groups calling for their removal claiming that they were inaccurate and fuelling stigma in the country.

Societal attitudes towards the procurement of abortion care

Another barrier to safe abortion care is the stigma which is partly fuelled by gender stereotypes. Societal attitudes towards young women who procure abortion care remain largely negative and studies show that psychosocial and cultural barriers are to blame for women not seeking abortion care from healthcare facilities. Participants in the study stated that religious beliefs, community norms and cultural traditions directly and indirectly influenced their decision to seek out abortion care. In addition, the study found that many communities use isolation and shame as tools to ensure that women do not break away from tradition such as labelling them immoral and hypersexual. The fear of stigmatisation founded on negative religious and cultural beliefs held constitutes a major barrier to the access of safe and legal abortion care.

2. What are the barriers to access basic contraception?

Contraceptive use remains low among the youth in Kenya as 73% of sexually active single women aged 15-19 report not using any contraception method.

Lack of adequate information

A 2014 survey revealed that young people identified inadequate information on reproductive health as one of the main reproductive health problems faced. Although policies geared towards informing the youth on their sexual and reproductive rights exist – such as the re-entry policy of 1996 and the 2015 National Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Policy –, these have been poorly implemented.

Misconceptions relating to contraception persist. According to the Kenya Demographic Health Survey, non-users of contraception cited fear of side effects and health concerns related to their use as reasons for avoidance or discontinuation of the use of contraceptives. The survey found that the fear of being rendered infertile prevented participants from using contraception. Some even believed that the use of contraceptive methods may lead to the disruption of natural body processes, birth defects and even cancer. Other side effects noted included unwanted weight changes, bleeding and headaches.

The absence of information is sorely felt by Kenya’s youth: a national 2014 demographic survey found that 3 out of 100 girls had children by age 15, with the number rising to 40 out of 100 girls by age 19. Regrettably, teenage pregnancy in Kenya almost always leads to school drop-out and about 10,000 and 13,000 girls leave school each year.

Service provider restrictions

The lack of information is compounded by barriers introduced by family planning service providers themselves. A study revealed that more than half of service providers imposed minimum age restrictions on one or more methods of contraception and that private facilities were significantly more likely to impose barriers across all methods of contraception. These medical barriers are essentially used to determine who can and cannot receive certain types of modern contraceptive methods and may contribute to the unmet need of family planning.

Financial constraints to access

Contraception is yet another area where resources matter – both at an individual and institutional level. A qualitative study conducted by Population Services Kenya on the barriers to the use of modern contraceptive methods found that access and use of modern methods of contraception by young adult women is significantly influenced by their income or financial stability. In a study carried out on barriers faced by young women in Mukuru Kwa Njenga Slums, one participant stated that:

when you have children, food and other needs to take care of, you lack the money to buy emergency pills or go for an injection…

Despite the government having declared its commitment to ensure the availability and security of contraceptive methods to enable desired family planning, obstacles remain. Public hospitals are failing to stock family planning commodities due to bills pending with the Kenya Medical Supplies Agency. Further, out of 784 public hospitals over 66% of facilities ordered contraceptives but did not receive the shipment. Therefore, the lack of adequate stock as well as the socioeconomic status of women are major impediments to access of modern contraception in the country.

Negative societal attitudes towards contraception

Research conducted by the International Centre for Reproductive Health Kenya revealed that 53 percent of Kenyans strongly believed adolescents on family planning were promiscuous. Another survey by Population Services Kenya found that there seemed to be a belief held by men that the use of contraceptive pills encouraged promiscuity among women, with a male respondent reportedly stating that the use of contraceptives enabled women to have extra-marital affairs knowing that they will not get pregnant.

The negative attitudes towards contraception may also permeate the family home, with real consequences for women. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF), it is men who usually decide on the number and variety of sexual relationships, timing and frequency of sexual activity and use of contraceptives, sometimes through coercion or violence. UNPF notes that not only do married women frequently hide their contraceptive methods for fear of violence, but community health workers seeking to provide family planning education and distribute contraceptives have faced hostility from men.

Cultural and religious practices and influences

Cultural practices may also play a significant role in deterring the use of contraceptives. According to one study, polygamy in western Kenya results in a general reluctance to participate in family planning. One female participant stated that men’s preference for the boy child means they are forced to give birth endlessly until they give birth to a boy.

In parallel, religious groups advocate for natural family planning and consider the use of contraceptives to be inconsistent with the faith. Faith leaders are important gatekeepers in disseminating reproductive health messages and influencing positive behavior change within communities. And because 85% of Kenyans are Christian, the church’s official stance against family planning measures is one explanation behind the low use of contraception.

3. What are the hurdles in accessing non-biased medical reproductive health information?

The current medical reproductive health information reinforces the already existing perception that family planning methods are for women as opposed to men. In 2016, the National Council for Population and Development in Kenya cited that the lack of adequate knowledge and information on contraceptives may cause men to perpetuate fears, rumours, myths and misconceptions about specific methods. An earlier study showed that very few providers in Kenyan public health facilities knew how to perform a vasectomy. Gender education and support for vasectomies at a national level are therefore key measures to redress the gender imbalance in the take-up of contraceptive methods, and promote couple centred family planning. Until these measures have been adopted, reproductive health is likely to continue to be seen as a distinctly ‘female issue”.

Often, individuals look to religious groups and organisations for their understanding of their medical reproductive health needs, and access to reproductive health information may or may not be discouraged by religious beliefs. Results from a study in Korogocho slums indicated that 51% of the sample agreed that contraceptive use was against their religious beliefs. Many of the respondents came to the opposite conclusion, with 41% agreeing that their religion approved of them seeking reproductive health services information.

The reality is that religious communities and leaders are often staunch opponents of family planning programmes. Religious organisations with a presence in Kenya, such as Human Life International, are known to oppose contraception, comprehensive sex education, and abortion care in all circumstances.

4. How is the use of technology influencing the reproductive rights space?

Mobile chat services

The use of technology in the reproductive rights space in Kenya is still at an early stage, and is harnessed by organisations supporting the exercise of reproductive rights. An example of this is Lily Health, a subscription mobile chat service which provides women with sexual and reproductive health advice via mobile messaging through Facebook messenger, WhatsApp and SMS. Lily Health allows women to text questions to “Lily” and receive responses based on a database of information about reproductive health as well as personalised information about that woman’s cycle. It would therefore appear that Lily Health is heavily reliant on user data.

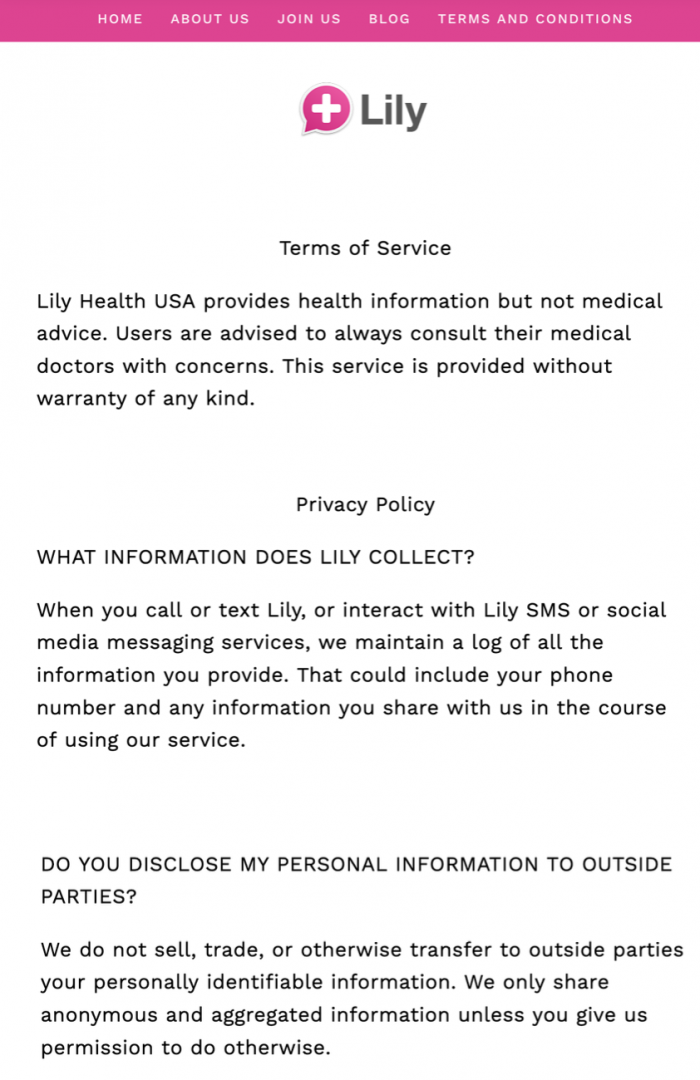

Lily Health seemingly operates two websites. The first contains multiple tabs including terms of service, where it describes itself as Lily Health USA. The second only has a landing page, and is ostensibly aimed at a Kenyan audience given the statement "For only 66 bob you can try Lily for one month". The first website does not link to the second, and vice versa. Both websites, however, are branded as Lily Health and use the same imagery.

Unlike the US website, the Kenyan website contains a chatbox linked to Facebook messenger prompting to start a conversation with Lily. However, no privacy policy or terms of use are apparent from that website. Conversely, the US website states the following:

The Lily Health privacy policy states that it maintains a log of all information provided by the user, including phone number and any other information shared with Lily Health while using the service. This is directly at odds with a comment made by a founding member of Lily Health, MacGregor Lennarz, that Lily Health “doesn’t require data”.

The policy also states that Lily Health does not share personally identifiable information with third parties without first being given permission by the user.

In 2018, Lily Health was reportedly planning to develop machine learning capabilities:

Machine learning will enable Lily to create an automated and scalable product that responds to customers using a database of customer details, reproductive health information, and a steadily improving algorithm that interprets customer questions in order to generate accurate responses – a “chat bot” solution

Period-tracking apps for girls

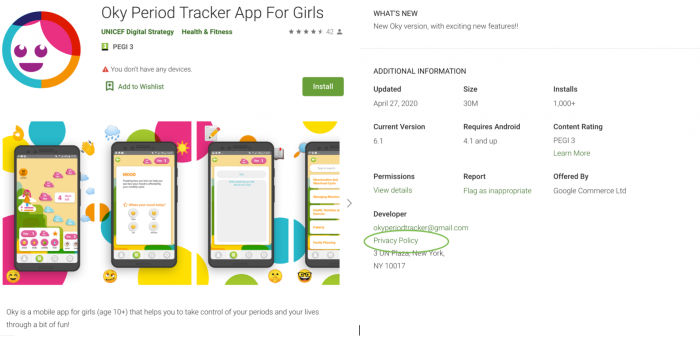

Oky is a UNICEF-developed Android app aiming to provide girls with information about their periods through features including individualised cycle trackers and calendars, tips, and menstruation information. Piloted in Indonesia and Mongolia, Oky is planned to be launched in Kenya in 2020 - the first African country to have access to the app.

Oky is described as being a novel app which is culturally appropriate, localised, digitally inclusive, open source and with high data privacy and security:

In a region where girls typically share phones with family members or with friends, and where data privacy risks are often gendered, data security is critical. That’s why Oky requires individual log-in information with password protection to ensure that girls can access information and track their periods privately, with their personal data only ever stored locally on their device.

The Oky app can be found through the Google Play store, which links to a privacy policy.

The privacy policy available on the Google Play Store links directly to UNICEF's own [4]. However, UNICEF's privacy policy states that it applies to sites within "the Unicef.org" domain name, seemingly excluding the app. In fact, the privacy policy omits any mention of apps. The policy goes on to state:

UNICEF sites with specific requirements to collect personal information may publish a privacy policy specific for that site. In these cases, the site-specific policies will be complementary to this general UNICEF privacy policy, but will give additional details for that particular use.

Despite the above mentioned statement, neither the Google Play store nor the official Oky app website provide any further information regarding the privacy policy. The Oky website nonetheless states that it "maintains the highest privacy and data protection standards".

5. What foreign organisations have a large anti-reproductive rights presence?

There are two foreign organizations that have sparked public debate and participated in campaigns against reproductive rights in Kenya.

CitizenGo

CitizenGo is a Madrid-based, community-led international advocacy group founded in 2013. Through their online petition platform, anyone can send their petitions to local, national and international government bodies and businesses. They have team members located in fifteen cities on three continents who facilitate users signing petitions in 50 countries. Their petitions defend various Christian and catholic causes.

Last year, the United Nations Population Fund partnered with the governments of Kenya and Denmark and hosted the International Conference on Population and Development (ICD+25) in Nairobi. The conference listed 12 commitments up for endorsement including abortion, contraception for children under the age of 18 and the sexualization of children through sexual education. CitizenGo led protests throughout the period of this summit marching through downtown Nairobi. They carried signs such as “Abortion Kills Our Children,” chanting “No to ICPD,” “Abortion hurts women,” and “Marriage is between a man and a woman.” CitizenGo also went ahead releasing a petition signed by over 68.000 people calling for Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta to reject the "pro-abortion and sexualization agenda" at the summit stating it was against the spirit of Kenyan law and culture.

According to their website, CitizenGo is wholly financed through small online donations made by citizens throughout the world from as little as $5. They do not accept financial support from public or private entities.

Human life International (“HLI”)

HLI was established in 1981 and consider themselves the world’s largest global “pro-life” apostolate, with an active network in over 100 countries, including Kenya. In 2015, HLI started a campaign against condom use by erecting a banner in a rural town in Kenya. The campaign was an attempt to condemn the advertising of condoms in all media platforms which they believed were always misleading and encouraging the youth to engage in sexual activities before marriage. In addition, the banner was said to convey the message that condoms cannot prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS.

In response, the National Aids Control Council (“NACC”) took hold of the banner and in exchange for its return demanded that the church stop its campaign. Instead, HLI led protests along with five other NGO’s outside the NACC’s building and threatened legal action should the NACC fail to return the banners it had pulled down within 14 days. They also publicly denounced the ICPD+25 summit in Nairobi by partnering with other pro-life and pro-family entities and creating an alternative summit dubbed the “Vita et Familia ICPD25”. They accused the summit of having blocked all pro-life, pro-family individuals and organizations from online registration and attendance, and publicly stated the summit to be an affront to African religious freedom.

Even more notable is HLI's alleged involvement in a 2010 campaign rejecting the country’s new constitution which legalized abortion if circumstances where a person needed emergency care or her life or health was in danger. The HLI Kenya Council chairman at the time, George Kegode, was quoted stating that: “the issue should not be whether to legalize abortion, but establishing why it is on the rise”. He also stressed the need to “first address reasons why abortion is rife”. Following the promulgation of the Constitution, HLI also opposed the 2012 Guidelines with its country director Father Raphael Wanjohi asking: “who has given these individuals the right to decide who should die?”, and further asserted that the role of the church is to safeguard human life.

It appears donations can be made by anyone to fund HLI's activities from an amount of $20 upwards. They even provide different charitable planning options such as wills and living trusts, charitable gift annuities and charitable remainder trusts. Other creative ways include the Real Estate for Life program, allowing those buying or selling a house to contact a Real Estate for Life pro-life realtor, who shall donate a portion of their commission to HLI.