Facewatch: the Reality Behind the Marketing Discourse

- Facewatch is allegedly developing a facial recognition technology that will work when people are wearing masks

- Statements by the CEO of Facewatch and marketing documents suggest the company is partnering with police departments in the UK - but the reality is unclear

- Beyond the marketing discourse, this situation stresses the impending need for more transparency when it comes to partnerships between police forces and companies selling surveillance technologies.

As more and more of us feel compelled to cover our faces with masks, companies that work on facial recognition are confronted with a new challenge: how to make their products relevant in an era where masks have gone from being seen as the attribute of those trying to hide to the accessory of good Samaritans trying to protect others.

Facewatch is one of those companies. In May 2020, they announced they had developed a new form of facial recognition technology that allows for the identification of individuals based solely on the eye region, between the cheekbones and the eyebrows, and that they would upgrade the systems of their subscribers accordingly.

Leaving aside the efforts of companies dealing with facial recognition technology to remain relevant in a post-Covid world, it is worth paying close attention to a company like Facewatch that has often talked about its alleged partnerships with public authorities in the UK. In this piece, we will take a closer look at what Facewatch offers its subscribers and investigate their alleged relationships with police forces.

What’s Facewatch?

Facewatch is a company that was founded in 2010 by Simon Gordon, the owner of Gordon’s Wine Bar in London. Facewatch describes itself as a “cloud-based facial recognition security system [that] has helped leading retail stores… reduce in-store theft, staff violence and abuse.” The company is now working internationally, with distributors in Argentina, Brazil and Spain.

The way Facewatch initially worked was that businesses (shops, bars, nightclubs…) would install Facewatch cameras in their premises. Using the footage from those cameras they would be able to identify “subjects of interest”, for instance, people who were seen on cameras stealing from the shop or displaying antisocial behaviour or generally anyone they did not wish to see in their shop. They would therefore create and store a list of effectively blacklisted individuals.

By scanning the faces of everyone who enters a shop and comparing them to the faces of those blacklisted, Facewatch is able to identify if a person who enters is on the blacklist or not. If they are, the shop owner receives an alert to inform them a subject of interest (SOI) has entered the premise, along with a picture of the person.

But Facewatch does not stop there. The company centralises the list of SOIs that their subscribers upload, and they may share them with surrounding subscribing businesses. So, for example, if you run the Facewatch software in your grocery store and the pub across the street also uses Facewatch and identifies John Smith as a SOI, John Smith will also be added to your “blacklist” and you will be alerted when he enters your grocery store, even if you have had no prior interaction with John Smith.

Facewatch has also allowed their users in the UK to file police reports automatically upon witnessing a crime. Facewatch users could send the police footage of a crime being allegedly committed. According to articles dating back to 2011, users were “given a crime reference number straight away” so that they could “follow the details of their case online.” At the time, Simon Gordon had said that “it helps if a business's local police force is supporting the scheme, because the process is more streamlined.”

It is unclear what the specific nature of the agreement was between the police and Facewatch before 2019 – in 2015 Gordon had told the BBC that 13 police forces had joined the scheme.

A FOI request filed in 2012 regarding to the Camden Borough Council revealed that, as part of its “Community Safety Budget 2011-2012,” the council had spent £1,800 for a Facewatch Trial, describing the purpose of the expenditure as “Police/licensed premises project: anti-violence.” It is unclear whether those expenditures had to do with the local police supporting the scheme or if they were themselves trying out Facewatch as subscribers.

But in 2019, a new partnership between police forces and Facewatch started gaining attention: the police and Facewatch were about to start an official agreement to share and receive data with and from the police.

Facewatch and the police: what is Facewatch saying?

According to the FT, Simon Gordon announced in 2019 that Facewatch was about to sign a data-sharing deal with the London Metropolitan Police and the City of London police, and was “in talks with Hampshire police and Sussex police.” In July 2019, Facewatch was still reported has having been “in talks” with the London Metropolitan Police and the City of London police. Quoted by the FT, Mr Gordon claims that the “deal with police is they give us face data of low-level criminals and they can have a separate watchlist for more serious criminals that they plug in…If the systems spots a serious criminal, the alert is sent directly to the police, rather than to retailers”.

The idea behind those deals was to have the police share with Facewatch subscribers lists of low-level criminals for shopkeepers to be informed when they come in on their premises. But there would also be a separate list for more serious criminals. Shopkeepers would not have access to that list and when a serious criminal enters a shop, an alert would be sent directly to the police, not to the shopkeeper.

Similarly, in Brazil where, as of February 2019, Facewatch has been used in three malls, the governor of Rio de Janeiro, Wilson Witzel, a supporter of the Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, also said he planned to allow the police to share their watch list of suspected criminals with facial recognition companies. This is people who have not been charged with a crime and have not been convicted by a court.

Digging beyond PR – what do we really know about the Facewatch/police partnerships?

According to Facewatch’s profile on the Digital Marketplace, a UK government website that allows tech companies to offer their services to government branches:;

“Facewatch is a secure cloud-based platform that uses facial recognition technology to send instant alerts to businesses or police when subjects of interest enter business premises. Facewatch also provides secure access control using facial recognition for use in Govt properties (eg prisons) enabling comparison of visitors across properties.”

The main difference is that in the list of benefits, we find two things that differ from how Facewatch seems to be marketing itself to business owners on its website: “Track Major Crime suspects in real time via camera network”, “Share watchlists of low risk criminals with businesses securely.” These are the features that Gordon referred to when he claimed that he was about to sign a data sharing deal with police forces.

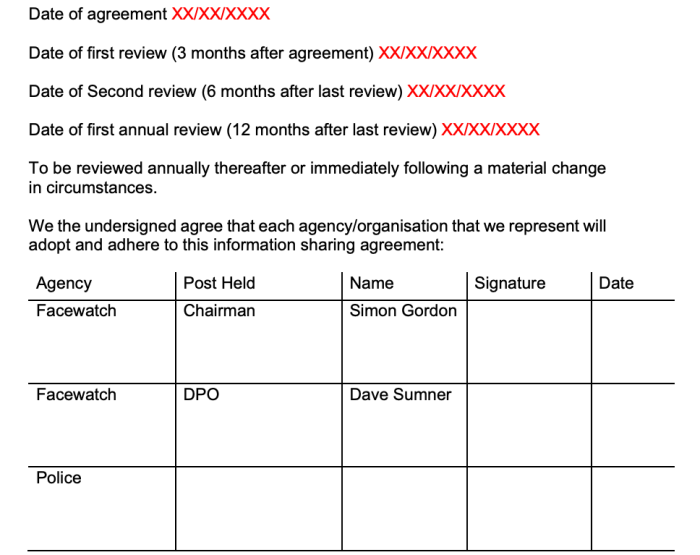

“Terms and Conditions”: an unsigned template data-sharing agreement between Facewatch and the Metropolitan Police

Available on the Digital Marketplace is a “Terms and Conditions” document, which is in fact a 34-page pdf that was meant as a draft Information Sharing Agreement (ISA) between the Metropolitan Police (Met Police) and Facewatch, and is now used as a template.

The draft ISA goes on to describe exactly the type of deal that Simon Gordon had said he was about to sign with the Met Police back in February 2019. It describes how information about low level criminals would be shared with Facewatch, while the police would be able to use the Facewatch network of facial recognition cameras to track high level criminals without having to share details about those individuals with Facewatch subscribers.

So… Did the Metropolitan police ever sign that agreement?

Privacy International is not aware whether Facewatch has in fact entered into any such agreements with any UK police force, and has not received a response from Facewatch when we asked the company in June 2020 and again in September. In response to a Freedom of Information request, Reference No: 01/FOI/19/002194 (attached), the Metropolitan Police Force confirmed to Privacy International that they did not have “a copy of any data sharing agreements or similar such contracts with FaceWatch” between 1 January 2015 and 10 May 2019.

The lack of contracts relating to the use of facial recognition technology between the Met Police and private companies was reaffirmed following the October 2019 revelations that a property developer was using facial recognition software around the King’s Cross site for two years from 2016 without any apparent central oversight from either the Metropolitan police or the office of the mayor. The Met Police produced a report admitting that images of seven people were passed on by local police for use in the system in an agreement that was struck in secret. In the same report, the Met Police underlined:

The MPS is not currently sharing images with any third parties for the purposes of Facial Recognition.

Can we trust the “Facewatch cop” to police us?

Public private surveillance partnerships are highly problematic. They raise serious human rights questions regarding the involvement of private actors in the use of invasive surveillance technologies and the exercise of powers that have been traditionally understood as the state’s prerogative.

In their Privacy Notice, Facewatch define Subjects of Interest (SOI) as people “reasonably suspected of carrying out unlawful acts (evidenced by personal witness or CCTV) who have been uploaded to Facewatch by our business subscribers to our Watchlist”.

We wonder what is it that makes someone “reasonably suspect” that a person is a potential criminal. What is the exact standard of reasonableness applied in a private company context or what are the company’s due process guarantees which we would normally have against the police? How can a private company employee make up for the professional training and codes of practice embodied in the police, in a time when even the latter, for instance, seems to be incapable of preventing racial injustice.

This could potentially mean that people might be blacklisted from local shops regardless of whether they have actually committed a crime or not and they will have no recourse or no way to appeal if they are. Imagine a situation when a heated argument at your local pub leads you to being flagged as a SOI and prevents you from shopping at your local supermarket, especially as other shop owners will not know why you have become a SOI.

We need more transparency before it is too late

The fact that so many public/private partnerships happen behind closed doors and require the hard work of citizens and journalists filing FOI requests to shed light on what is happening in our streets is a problem.

The UK Information Commissioner’s Office is currently investigating “the use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement in public spaces and by private sector organisations, including where they are considering partnering with police forces.” We urge them to expose any surveillance partnerships that may have escaped the necessary scrutiny as a lot of those companies are not even known to the public.

Assigning pre-emptive policing functions or endorsing the existence of private surveillance networks distorts long-established societal premises of privacy and perceptions of authority. If left unchallenged, public-private surveillance partnerships can eventually normalise surveillance, and consequently erode not only our privacy rights, but also fundamental freedoms, as they will inevitably chill our right to protest, our ability to freely criticise the government and express dissenting ideas; the very essence of what makes us human.

Conclusion – impact for the rest of the world

While Facewatch has been developed in the UK, they have not been shy regarding their international ambitions. As we stated earlier, Facewatch is already present in Brazil and have distributors in Argentina, Brazil and Spain. And while individuals in the EU might still be able, for example, to file data Subject Access Requests and find out whether their facial images are being held by Facewatch or Freedom of Information requests to shed light on suspicious deals, in countries with weaker legal frameworks, the problems will become all the more concerning.

It is high time we tackled the wider question of whether we want to be living in a society where corporations are allowed to roll out intrusive biometric surveillance, such as facial recognition, and at the same time collaborate with the police to put us on watchlists. We believe this should not be the case.