We asked five menstruation apps for our data and here is what we found...

We asked five menstruation apps to give us access to our data. We got a dizzying dive into the most intimate information about us.

- Out of the five apps we surveyed, two apps responded well and fully to our DSAR, one app did not give us our data, one never responded, and one is refusing to let us publish our data

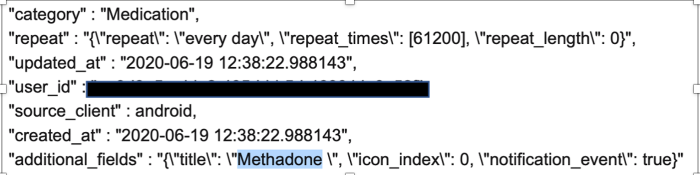

- The apps that did respond handed us multiple pages of our most intimate data, including data about our sexual life, our masturbation habits, our medication intake.

- Some of that data was shared with third parties

In 2019, we exposed the practices of five menstruation apps that were sharing your most intimate data with Facebook and other third parties. We were pleased to see that upon the publication of our research some of them decided to change their practices. But we always knew the road to effective openness, transparency, informed consent and data minimisation would be a long one when it comes to apps, which for the most part make profit from our menstrual cycle and even sometimes one’s desire to conceive a child.

This year we decided to approach menstruation apps from a different angle. Using our right under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), we asked five menstruation apps to share the information they hold on us. A PI employee used the apps for a brief period of time and wrote to the companies asking for her data. This is called a Data Subject Access Request (DSAR) as per the right of data subjects to access their data. Companies have to answer them within a month. To find out more about how you too can file a DSAR, check out our guide here. You can find the template of the DSAR we filed for this paper at the bottom of this page. In the UK, GDPR still applies during the duration of the transition period and has been transposed into UK domestic legislation by way of the UK Data Protection Act 2018.

We were hoping to find out:

- if the selected menstruation apps were complying with their obligations under GDPR and actually respecting the right of data subjects to access their data by responding to us

- how good they were at respecting this right to access information by sending us clear information about what they hold in a way that could be easily understood

- their ability to provide us comprehensive and complete responses to our questions about their processing of our data

- what data they actually collected and stored about us

This is not a ranking of menstruation apps nor an endorsement of their processing activities and their compliance with the law. The apps are listed in alphabetical order.

Clue by BioWink

- Based in Germany

- 10M+ downloads on Google Play Store

Clue provided us with a back-up of our data, as well as a PDF giving answers to our questions, and two Excel files containing the data they hold on us – one entitled “Single User for Support Team” containing general data about us (“user ID,” “name”, “location”) and the other one entitled “User Data Request Query” containing data on every interaction we had with the app.

In the first Excel file, we get to see the data they hold about us as a user. Among the information they potentially have access to was birth year, birthday (both mandatory to sign up), subscription to their newsletter and in which language, if the birth control section had been filled, and if Fitbit was enabled.

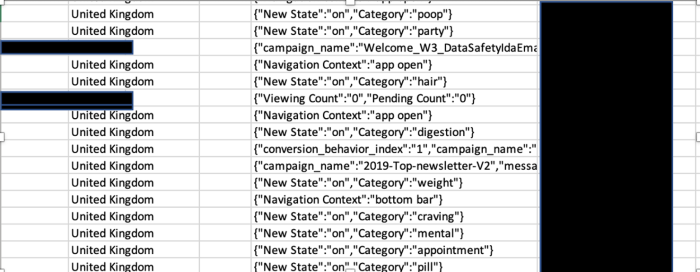

The second file shows the data they retain for each “request query.” So, every time we interact with the app, this information is collected and stored. This information is tied to our user ID, our device ID but also to our location. We had to redact our location in order to protect the privacy of our researcher but it was precise enough to identify the borough and administrative districts of where they were located.

The screenshot revealed some of the entry in that file. We noticed some of the data we had entered about our stools (“poop”), about having listed partying as an activity, about our hair, our mood “craving” or our birth control habits, “pill.”

In the PDF, Clue addressed the questions we asked them. However, as can be seen from the DSAR letter published below, question “e” was as follows:

“In case my personal data was disclosed to any third party, specific details about each recipient, the data shared with them, the purpose(s) and legal basis for sharing, as well as the details of the agreement entered into for this sharing.”

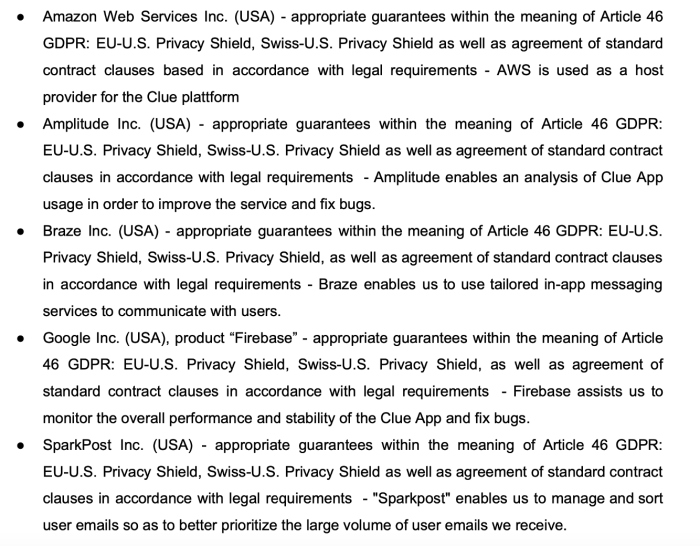

We did not initially receive a list of all of those third parties, however, we did receive a list of the companies they shared our data outside of the EU. The list is as follows:

In a follow-up email to us, Clue admitted that they did not provide us with a full list of third parties and that this was an oversight on their part. Clue also informed us that all the third parties they share data with are listed in their privacy policy. We can confirm that a list of these third parties is indeed provided in their privacy policy.

Clue Summary:

- They responded to our DSAR

- They sent us a copy of our data. While an Excel format is an acceptable way to send personal data as part of a DSAR, we note that it is however not the easiest way to read and understand the data they process about users.

- Every interaction we had with the app resulted in data that was stored on Clue’s servers.

Flo by Flo Health, Inc.

- Based in the US, with EU representatives in Cyprus.

- 50M+ downloads on Google Play Store

Flo sent us a password-protected back-up of our data as well as two PDFs. One contains the data they stored on us in a readable format, the other one is a PDF answering every single question we asked them. They asked us to confirm that we had downloaded the back up of our data for them to then delete our data.

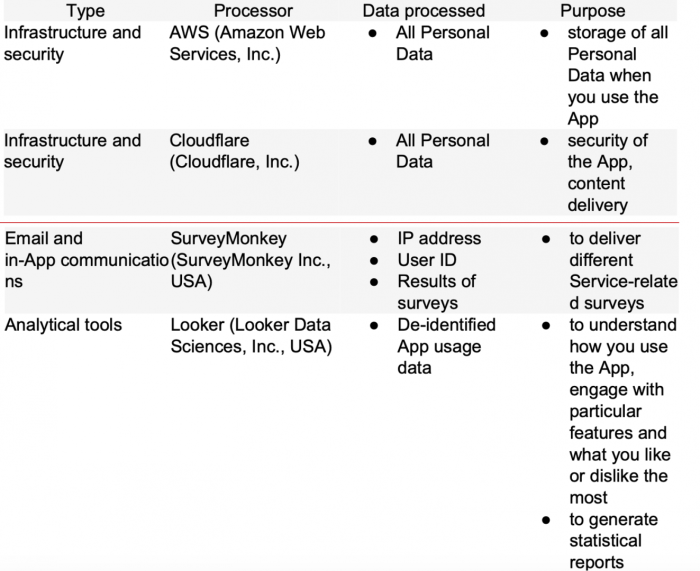

In the PDF answering our questions, Flo provided the full list of third parties they work with – regardless of their location – and a clear description of the type of data they are sharing with these third parties. Their definition of personal data is included in their privacy policy.

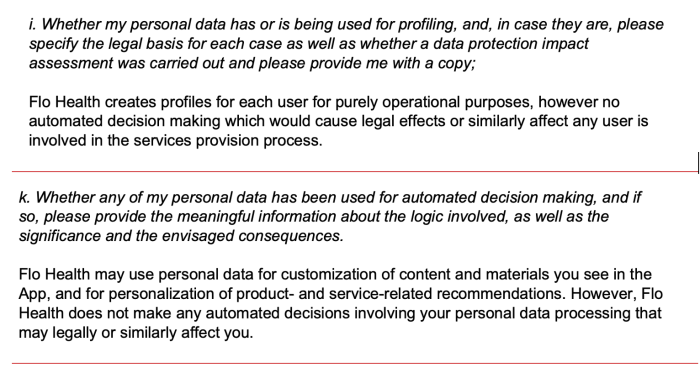

While they argue that they did not conduct any automated decision making which would cause legal or similar effects on users, we believe that the transparency principle upheld by GDPR means Flo should strive to inform their users of how they are being profiled if at all, what the automated decision consists of (even if it is not of legal effect), and how it is used.

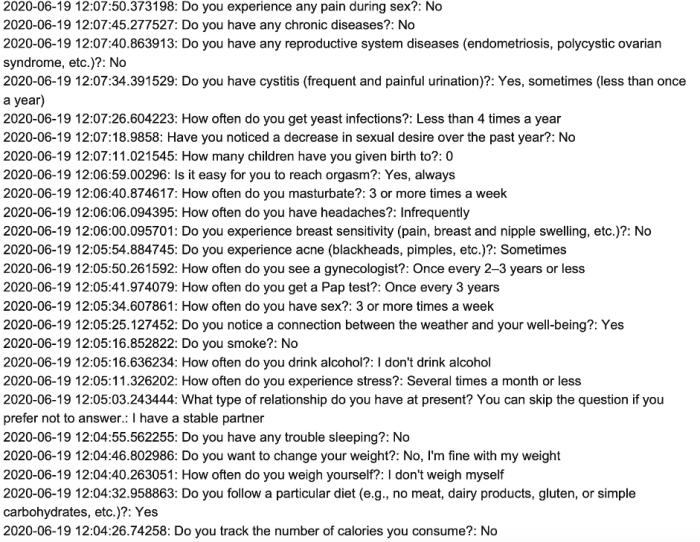

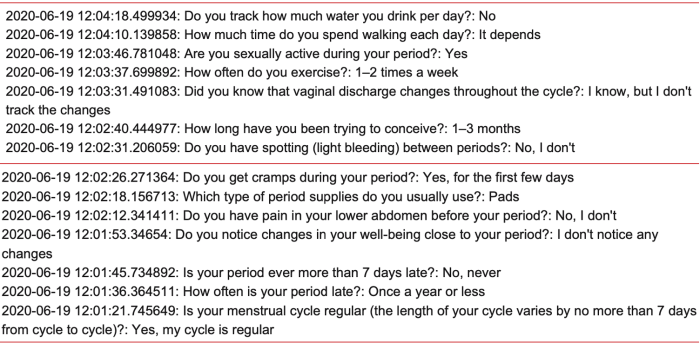

In the PDF containing our data we were able to see the data that Flo has collected on us, as well as metadata like collection time. It is worth noting that a PDF format is more easily readable and understandable than the Excel document such as the one provided by other companies.

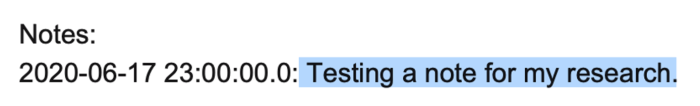

Like other menstruation apps, Flo offers an option to write notes. We wrote “testing a note for my research” to see if we would be able to retrieve this text in the DSAR and it was indeed contained in our DSAR, which means the content of notes are not stored locally on users’ phone but stored in Flo’s servers.

Accessing our data gave us a dizzying insight into what menstruation apps have access to. As we used the app, we were encouraged to enter more data. While there was nothing at odds with their privacy policy, reading the full extent of what we had entered – even though we only used the app for a few minutes – offered us a completely different perspective. This raises larger issues with the way menstruation apps encourage users to give away their data without providing further information on privacy implications beyond the privacy policy or even explanation as to why this data is collected in the first place, especially as sensitive personal data is at stake. Beyond the question of lawfulness, we should not lose sight of the importance of users' perception: whether users realise that their most intimate data is not just staying between them and their phone but actually collected and stored in a company's server.

Flo Summary:

- They responded to our DSAR.

- They sent us a copy of our data as a PDF, which made it easy for us to read and understand.

- They answered all our questions in a clear way.

- Every interaction we had with the app resulted in data that was stored on Flo’s servers.

Maya by Plackal Tech

- Based in India

- 5M+ downloads on Google Play Store

Maya never responded to our DSAR despite our reminder and despite the fact that we were clear this was their legal obligation.

Maya Summary:

- They did not respond to our DSAR and thus did not comply to their obligation under GDPR.

MIA by Femhealth Technologies Limited

- Based in the British Virgin Islands

- 1M+ downloads on Google Play Store

MIA responded to our DSAR within the time frame and answered all of our questions.

However they prohibited us from publishing the response, whether in full or in part. MIA’s argument for preventing us from publishing is that the information contained in the DSAR response was either a trade secret or is covered by copyright.

Their decision not to allow us to publish is untenable for two reasons:

- By asserting confidentiality in respect of the entirety of the DSAR - including those parts which contain personal data - MIA are purporting to establish ownership and control of personal data that is, in fact, ours. We entered information about our sexual life, our masturbation habits, the quality of our stools and our oily skin. We were surprised to see such information turned into a “trade secret” or otherwise protected by “copyright”.

- Any MIA user filing a DSAR will be lawfully entitled to the information MIA is so keen to protect from publication, including categories of data held, third-parties with whom the data is shared, and for what purpose. If you want to know how MIA responds to a DSAR (or just their trade secrets), you can just open an account and email [email protected]

We also want to add that for every app we contacted, including MIA, we made it clear that we would be publishing their response on the DSAR itself.

While this is not a data protection issue, MIA’s behaviour raises questions about their commitment to comply with the principles of transparency and accountability. The basic tenet of informational self-determination is being able to use the information we receive from a data controller however we want and share it with others if we wish to do so.

MIA summary:

- They responded to our DSAR.

- They are preventing us from publishing the DSAR response on tenuous legal grounds.

Oky by UNICEF

- Created by Unicef for girls aged 10+ in an effort to educate them about menstruations

- 10,000 downloads on Google Play Store

Oky is an app created by Unicef aimed at girls to promote their education regarding periods and their health. It is available on Android only and seeks to address the taboo around menstruation that exists around the world. The app was developed as a result of consultations with girls in Mongolia and Indonesia. The app brands itself as being very privacy-oriented, with one of their slogans claiming "It's Oky, it's private."

While they define themselves as an "open-source app," that claim appears to be inaccurate as the source code is only available upon request. In order to be labelled open source an app needs to publish their source code and ensure that it is accessible to all. A more accurate term would thus be “source-available.” We requested access to the source code, however, at the time of publication, this has yet to be granted. It therefore remains unclear which license any source code would be distributed under and whether that is compatible with open-source software principles.

Before we published this report, we wrote to Unicef to give them an opportunity to respond to our findings. In their response letter Unicef argues that “The Oky source code is publicly available on GitHub.” While we do not doubt this claim we have not been able to find it, nor is there a link available on their website.

Oky was the first menstruation app to respond to our DSAR. They have asked us not to publish their letters to us.

In their initial response they told us they did not hold any personally identifiable data about us. Since they did not store IP addresses, IMEI numbers or Wi-Fi Mac addresses, they could not identify our data.

After receiving this response, we contacted Oky to alert them that neither their website nor their page on the Google Play Store had a privacy policy (the Google Play Store page currently links to the standard privacy policy available on Unicef's website, which is distinct from the one available on the Oky app). It is worth noting that the Oky app has a privacy policy that is very clear and easy for their users to understand, but it is only available after you have downloaded the app.

We decided to schedule a call with Oky to discuss their general work. Prior to the call, we filed a second Data Subject Access Request. This time, we asked for our data based on our username (that we had not initially provided) to see if they could retrieve the information about our account with this information.

Their response was they did not hold personally identifiable data under our username, as they cannot locate any username in the database. They explained that they store usernames and non-identifiable data in the database, using a hashing algorithm to transform the username into a random string of characters. They said there was no way to reverse this hashing to find our username.

During the call we shared our concern about them not being able to retrieve the information we requested despite the hashing function – hashing is a component of an encryption suite. We asked them how the username was hashed and how the hashing function is salted (salting is a way to secure the hashing process). We explained to them that while a hash cannot be reversed, as it is a one-way function, if the user provides all the parameters for the hash function (what their username is for instance), we should be able to obtain our data. This is how we can retrieve our information when we log in from a different phone with a username and password, which is a function that Oky app enables.

However, in their response to us, Oky reiterated they were unable to share our data with us. They explained that five data points were used to register an account: gender, month and year of birth, location (country, region, rural / urban), and memorable question answer. They also added that what they refer to as intimate data (menstrual flow and mood) logged was stored locally on the user’s device and not transmitted to any backend.

The letter also explains that the registration function was created as users requested the option to log into their account when changing phones without losing any of their previous cycle data.

The cycle data is therefore not considered to be intimate data by Oky since it is not stored locally (as menstrual flow and mood data) but can be transferred from one device to the next.

We asked Oky again if they could at least provide the five data points used for the registration. Their response was that if a person had access to the source code, access to the hashing algorithm, access to the UNICEF database and knew our username, this person could find the 5 data points we entered about gender, month and year of birth, location and memorable answer. However, they added that they do not have anyone who has access to all three parameters and therefore they cannot retrieve the data.

We are therefore left with several unresolved questions when it comes to the way Oky processes the data of users, and if they are able to allow users to fully exercise their rights such as the right to access to personal data.

If a user chooses to register an account, some of their menstruation cycle data, which is considered sensitive personal information as it is categorised as health data, will seemingly still be stored in Oky’s remote server, despite what Oky’s emails to us appear to suggest, when they say only five data points could be retrieved. This is why users are able to access their menstruation cycle data when they change phones. This is something we were able to confirm as we used the same account from different phones and we were able to retrieve the menstruation cycle data we had entered on the initial device, as it is linked to the same unique username.

The Oky platform currently appears not to be able to comply with key data protection principles. However, as Oky is created by Unicef and Unicef, is a UN agency, it is not subject to the GDPR or any other national data protection legislation. This is because it enjoys privileges and immunities as an organisation of the United Nations. Nonetheless, we believe that Oky should comply with the UN's data protection principles and standards, as well as the standards set by legal frameworks like the GDPR. This is particularly important given that their mandate aims to protect children and their rights. Considering that Oky has recognised that children have the right to privacy, more transparency needs to be provided surrounding the protection of their personal data.

Oky's website claims that the app adheres to the highest privacy and data protection standards. As an app that holds itself out to be privacy-focused, they have even more of a responsibility to uphold recognised data protection principles and standards. The key principles of data protection - found both in the GDPR and in the UN principles - provide that data subjects have the right to access their data and to have that data deleted and corrected. By telling us they cannot either access our data or provide us with it, Oky is also de facto telling us they cannot delete nor edit our data. In other words, the current setup of the Oky app does not make it possible for people to exercise the full range of data rights, including rectification and erasure. This makes it difficult for Oky to live up to the high data protection principles and standards that they claim to uphold.

The system that Oky describes in their last answer to us - where no one has access to every piece of information - is essentially like putting jewellery in a box with two locks and giving the two keys to two different people. It does not mean the box cannot be opened anymore. It just requires a bit more effort on their part to open it.

In the letter they wrote us, as part of their right of response to this report, Oky insists that a username cannot be used to identify a person, while challenging our assertion that a username could amount to personal data. Considering they mention the British Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) as their point of reference on data protection, we would like to use this report as an opportunity to remind them that the ICO has declared usernames to be personally identifiable data. In the words of the ICO “An individual’s social media ‘handle’ or username, which may seem anonymous or nonsensical, is still sufficient to identify them as it uniquely identifies that individual. The username is personal data if it distinguishes one individual from another regardless of whether it is possible to link the ‘online’ identity with a ‘real world’ named individual.”

There are a lot of things that Oky does right: not making user registration mandatory, thus giving the option for users to have their data stored only on their phone, not requiring an email address, having a readable privacy policy... Yet the fact that they are unable to fully comply with a data subject access request remains concerning. This appears to suggest that Oky needs to improve its ability to be transparent and to keep a record of processing activities, in order to ensure users are able to exercise their rights.

Oky summary:

- They were not able to comply with their obligation to give our user access to their data.

- They are the only app whose default setting allows users to use the app without registering an account, which means the data is stored locally (on the device) in those cases. This is a function we would like to see other apps adopting.

Conclusion: some good, some bad but the need for a different approach remains

Out of the five apps we surveyed, two apps responded well and fully to our DSAR, one app did not give us our data, one never responded, and one is refusing to let us publish our data.

While we commend the effort on transparency from the apps that responded accurately, the picture we got is one where our most intimate information was collected and sometimes shared with third parties. Seeing our most intimate data in the responses was a stark reminder that the information we share does not stay between us and our phone but is also accessible by the app servers and potentially others. This sensitive personal information is also potentially vulnerable to attacks: while none of the apps that responded to our questions reported any case of data breach the reality is that every year both governments and companies alike are having security failures leading to data leaks.

Many of the apps have a user experience that incentivises entering more data: some give “points” for entering more data, some do not let you access the app services unless you enter data, others promise you a better and higher quality of service if you give more data. Yet, after providing all the information we were encouraged to enter into the app, we had to ask ourselves: did this benefit us? What was the benefit to us of the app knowing we masturbate three times a week or that we have trouble reaching an orgasm?

While apps would argue they are doing it in order to offer a more tailored experience, we think respecting the concepts of data minimisation and purpose limitation, where only data that is strictly necessary should be collected and only for certain purposes should be key in shaping the user experience for menstruation apps. We also think content can be offered without targeting the user based on their most intimate data.

Menstruation apps are a useful service that people rely on in their day to day life. They should be an empowering experience and not one where their data are exploited. To that end we suggest the following recommendations to menstruation apps:

Guaranteeing users anonymity and respecting their rights

- Registration should be optional, and should not require an email address.

- To the extent data is collected, data controllers should be able to hand over and delete user data when requested.

Data minimisation

- Data should be stored on the phone.

- Only data strictly required to provide information related to the menstrual cycle should be collected.

Informing users

- Users should be informed of their rights through accessible and user-friendly data privacy policies.

- Any data that is not strictly required should be labelled as such. The purpose for which the data, including non-essential data, is going to be used should also be clear to the user.