The case of the Solidarity Income in Colombia: the experimentation with data on social policy during the pandemic

In response to the pandemic, the Colombian National Development office devised an unconditional cash transfer programme in only two weeks. The beneficiary selection process, which was solely based on data already held by the government, remains shrouded in obscurity.

This piece was written by Joan López, researcher at Fundación Karisma, and originally posted on their website.

The uncertainty of this crisis has become an opportunity for the implementation of technological solutions to complex issues instead of coherent decision-making processes. During the social and economic crisis caused by Covid-19, the National Development Office (DNP in Spanish) in Colombia, in just two weeks, set up an unconditional cash transfer system for 3 million citizens. The program was called Solidarity Income (“Ingreso Solidario”). The objective of this article is to analyze the kind of social policy introduced by the Solidarity Income and its problems for building a fairer society.

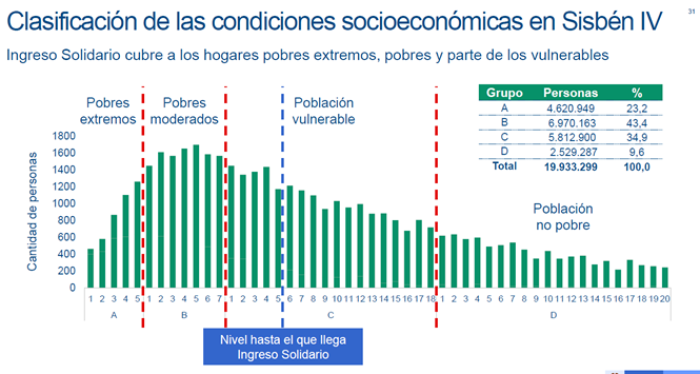

Since the 90s, Colombian social policy is liberal because it is based on targeting resources to people in poverty. In other words, the State created mechanisms to “search for the poor” and bring them the limited resources available. In this context, the System of Possible Beneficiaries of Social Programs (Sisbén in Spanish) appeared as the main instrument to target social assistance. This system rates people with scores from 0 to 100 in terms of “prosperity".

To understand the difference between the Solidarity Income and traditional social policy, we must understand how the allocation of a social benefit works in terms of the data used to identify the beneficiaries (See Table 1).

The first targeted social programs used an examination of the conditions of each household in which citizens were actors in the production of the data. The Sisbén score emerged from an institutional effort to “search” for vulnerable populations through surveys in impoverished areas that resulted in a score ranging from 0 to 100. Depending on the score, people are eligible for social programs managed by different state agencies. The needed score to be eligible is set by each program and agency.

The Solidarity Income changed the relationship between the data used to assign a benefit and the participation of people in the system. Amid the crisis, the response was an experiment that involved using as much data as possible to “find” people who “needed” but were not receiving traditional social programs. The program built a new Master Information Database, in which the National Development Office (NDO) mixed all kinds of administrative records. They used data collected for diverse purposes and managed by private and public actors. These databases have different levels of quality, and some were unknown to many Colombians. In other words, it is no longer a matter of “finding” vulnerable people in the areas affected by poverty but of “taking advantage” of the personal data that we are leaving in our interaction with different institutions.

The experiment ended up opening the Pandora’s box of the Colombian government information systems and showing their dependence on the private sector. When the NDO published the list of beneficiaries, many citizens reported inclusion errors regarding non-existent and expired ID cards.

The NDO’s response was to dismantle the database and deliver it to the National Civil Registry for deduplication. This process resulted in nearly 17,000 records with inconsistencies. After the incident, the NDO assured that the errors were inconsequential because the banks would verify the identity of the recipient before making a transaction. Also, in the case of communities with no access to financial services, the public agency used databases of prisons and the Forensic Medicine Institute to deduplicate IDs that were marked in those databases as deceased. This situation made clear that the State registries have serious quality problems and exposed a public policy reliant on the indiscriminate use of databases. How many people were unfairly excluded in the crosschecks with databases of uneven quality? We will never know. However, we can analyze the narrative behind the Solidarity Income. The bureaucracy is using these data-intensive solutions to avoid a political discussion that involves deciding who should be eligible for social redistribution in a time of crisis, the consequences for the lives of those excluded, and the alternatives we could offer them.

The selection of beneficiaries in the South, considering the high levels of poverty, unemployment, informality, and inequality, are particularly arbitrary results of data-based mechanisms. This practice of targeting implies a form of violence for people who are left out. Why did the NDO draw a line between potential beneficiaries in a pandemic on 8.7 million families when there are 17 million at risk of falling into poverty? This question requires a political discussion that depends on transparency and participation.

In this case, the state is taking away people’s agency to demand their social rights and actively participate in the political discussion. Data is not the reality but the representation of the politics of government and the social inequalities that shape it. The communities in poverty could be easily invisibilized or misrepresented by that system. The Solidarity Income's design makes the enforcement of citizens’ rights impossible. Those affected will hardly be able to request that information be corrected, obtain information on decision procedures, and challenge the results. Neither are they allowed to actively participate in the construction of the social policy that gives them agency in an emergency crisis.

Technocrats are hiding behind data and technological solutions to deny people the agency to participate in the state’s decisions, to call out injustice, and to claim the protection of their social rights. Hence, they call citizen complaints “myths” or deny the agency of outspokenly critical citizens by asserting that they are not deserving beneficiaries because the databases do not lie, so “there are no mistakes”. In other words, we are facing a government that unilaterally claims to know the people in need and denies their participation in the process. The government even points out how wrong the protesting voices are: they are being “manipulated” or “they want to skip the line”. In short, it is about using technologies and data to avoid having political discussions.

In conclusion, the Solidarity Income is an example of the worrying future of social policy in which people have fewer mechanisms to demand their rights from the State. It is also the evidence that the “true” beneficiaries will emerge from the data trail that we are inadvertently leaving behind and not from an exercise in active citizenship. The government sells the program as an innovation, but it was nothing more than a great experiment to roll out a data-intensive social policy. Thus, the State will automatically determine, through third-party data and in a non-transparent way, the peoples' “deservedness” of social benefits. A policy designed not to include but to eliminate “inclusion errors” and one in which citizens could not challenge the results. In other words, the government is constructing a dark system that will use as much data as possible to find the fewest possible beneficiaries.