Perspectives on the harms of unregulated fintech

This articles explores the use of digital loan Apps in Philippines and Kenya and highlights some of the common concerns that emanate from the unregulated use of such Apps.

- Technology has driven several changes in the way that financial services are packaged and accessed by consumers. These changes have led to the rise of fintech, a data intensive industry.

- Research shows that users have to give up excessive amounts of personal information as part of the loan application process.

- We call for closer regulation of these Apps as one way to reduce the potential harms they cause.

Introduction

Technology has driven a number of changes in the way that financial services are packaged and accessed by consumers. These changes have led to the rise of fintech, a data intensive industry that has been touted for its convenience and as an alternative to traditional financial services.

The current article looks at the use of digital loan Apps in Philippines and Kenya and contextualises the global discussions on fintech which we have been monitoring for some years. Research undertaken and published by our global partners, the Foundation for Media Alternatives (FMA) in the Philippines and the Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Technology Law (CIPIT) in Kenya highlights some of the common concerns that emanate from the use of such Apps.

We believe it’s important to consider the issues raised in this article against the backdrop of the Covid-19 pandemic and the socio-economic ramifications emerging already. One of the universal effects of Covid-19 has been a widespread loss of income due to the loss of jobs and a continuing global economic downturn. Research led by Pew Research shows that lower-income earning adults were the most affected by Covid-19 in the US. A similar pattern is evident in other parts of the world. According to estimates from the World Bank, Covid-19 potentially pushed about 49 million people into extreme poverty in 2020.

These populations who are in a precarious situation still have to source funds to meet their living costs such as housing, food, and in most instances, expenses associated with looking for a job. Bad credit records and a lack of reliable income make it hard for members of vulnerable populations to access loan facilities from traditional loan providers such as banks and credit firms.

This state of affairs has contributed to an increase in the use of App-based digital loans offered by private entities operating over the internet. Such services are attractive to individuals who need quick access to cash but lack the credentials to qualify for common credit services.

Filling a Gap

Digital loan Apps fill a gap left by the formal market of lenders. Bank loans for example, require that the applicant have a bank account. This is problematic given the high numbers of people that do not own bank accounts due to a variety of factors.

In Kenya, it is estimated that only about 41% of the adult population own a bank account. Estimates from the Philippines state that nearly 80% of adult Filipinos, are ineligible for bank loans. In Southeast Asia, around 300 million adults cannot access bank loans due to eligibility issues.

Many therefore, see digital loan App services as a practical alternative. They fill the gaps left by traditional lenders by offering easy access, lax application requirements, and an expedited approval process. Unlike banks, many of these lending entities do not perform elaborate credit checks.

The entire loan cycle happens online—from marketing to application, to the release of the loan, all the way up to collection and repayment.

Unlike conventional banking that requires collateral in the form of property, microfinance uses non-property guarantees for loans such as social reputation, financing to women’s groups as opposed to individuals, and other innovative guarantees.

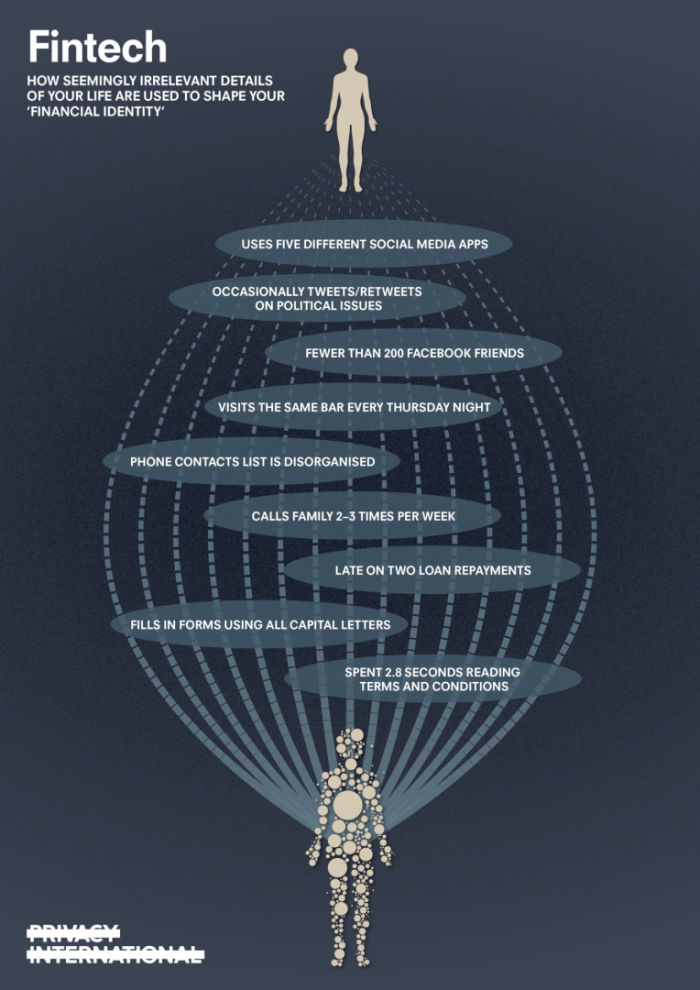

While lending Apps do not rely on traditional credit scoring service providers, the Apps do make use of behavioural data collected as one uses a mobile phone to determine credit worthiness. Examples of such data include type of phone, location, contacts, apps and mobile money transactions.

Other data may be derived from various sources like mobile transactions, electronic money usage, and credit history. Data from mobile phones themselves and the apps they contain are also utilised.

According to findings by FMA, the main target appear to be Android phone users between 21 and 40 years of age, most likely due to their income-earning potential. While specific procedures and requirements may vary between lenders, the overall process is made up mostly of common features. For example, many lending entities use social media sites and apps like TikTok, Facebook, and Google to promote their services.

Lending Apps and Privacy

The research conducted by CIPIT and FMA indicates that lending Apps collect information from the applicant’s phone as part of the process to assess that applicant’s suitability for a loan. Part of the information collected by these Apps includes calls, text messages, top-up pattern, data use, mobile money transactions and other digital payments, GPS data, social media use, Wi-Fi network use, battery level, and contact lists.

In some instances, other sources of digital footprints like the applicant’s use of cloud-based services, banking transactions, internet browsing, shipping activities, loan management, payables, and online recordkeeping are also considered.

Text messages, in particular, are sometimes analyzed to see if the user has already obtained loans from other lenders. Granting the loan App access to text messages makes it possible to look through text messages on the phone for this purpose. For some companies, the number of loan Apps and contacts they find in a phone helps make accurate credit risk evaluations.

Contacts have also been proved to be useful when it is time to coerce people to pay back their loans. In Kenya, at least seven different lending Apps have either sent texts, or even called a loan defaulter’s contacts in a bid to influence the borrower to make payment.

The research by CIPIT revealed that lending Apps require access to location data as well as network connectivity data. This could be for purposes of geo-locating the loans to Kenya. However, the apps have continuous access to location data, making it possible to track a borrowers’ movements.

For example, Okash, a Kenyan service provider, requires an extra location permission - ‘access extra location provider commands’. Coupled with the fact that the apps run at start-up and prevent the phone from sleeping, this raises issues from a data protection perspective, for example, informed consent, transparency and data minimisation, amongst others.

Another Kenyan service provider, Branch, requires access to the borrower’s phone microphone which enables it to record audio. Okash requires access to the calendar, which includes the permission to add or modify calendar events and email guests without the user’s knowledge.

The two research reports also show a number of other problematic issues relating to the use of these lending Apps. These common issues are discussed in detail below.

Lack of regulation

In the Philippines, online lending platforms are regulated primarily by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). However, lax enforcement of the regulations means that many lending entities do not bother with registration and licensing requirements, opting to operate in a regulatory grey zone. This makes it extremely difficult for authorities to monitor their operations. Another factor that encourages non-compliance with existing regulations is the lack of strong penalties for companies that are caught operating outside the law.

According to the FMA report, in 2019, the SEC issued cease-and-desist orders (CDOs) against 48 lending entities that did not have the necessary permit. As of 14 December 2020, the SEC lists only 75 registered lending entities, some of which were operating multiple apps.

Comparatively, Indonesia blocked 1,369 illegal lending platforms in 2019. Meanwhile in India, at least 60 loan apps featured in the Google Play Store were also found to be unregistered.

In Kenya 3 of the 7 Apps studied as part of CIPIT’s research did not fall under the regulation of the Central Bank of Kenya (‘CBA’). This is because the 3 Apps did not take any cash deposits meaning that their activites do not fall under the purview of the CBA.

Kenya’s 2019 Data Protection Act applies to the processing of personal information, including in scenarios such as the processing of such information by loan Apps. Ineffective implementation of this law may give these loan Apps room to continue operating as if they are without any regulations.

The narrow regulatory approach taken by countries such as Kenya, that only focuses on regulating the activities of traditional financial service providers and lenders means that loan Apps along with other emerging technology based service providers are left to operate largely unregulated.

In some instances for example, the Philippines, the legislation properly applies to the operations of loan Apps, but the oversight mechanisms are poor and companies exploit that.

Lack of transparency

According to FMA, the underwriting process of lending entities is very opaque, as are their digital and mobile marketing operations. Although most people who use such services are aware that they process data using algorithms and proprietary lending models, very few — even among their employees — know exactly how they work. This, too, makes oversight difficult (if not impossible).

As the FMA report points out, the lack of transparency on how lending Apps process applications make it hard to determine if specific groups are discriminated against, or are being unfairly targeted with predatory lending.

What passes off as transparency efforts are the loan app’s privacy notices and terms of use. Unfortunately, many of these documents are just as problematic. Some are run-of-the-mill replicas of other policies; others are inaccurate or patently deceptive. In India, research revealed that a number of loan Apps did not have any websites, while some had their privacy policies written in a Google Doc.

Unlawful, unethical, or questionable debt collection practices.

Many complaints against lending entities revolve around their debt collection practices. Collection agents have been known to employ verbal abuse, harassment, and public shaming in going after defaulting debtors.

There have also been reports of lenders posting a borrower’s selfies on Facebook, changing the borrower’s profile picture on the social media platform, and using the borrower’s account to post a threat.

The experience of other countries paints an even grimmer picture. In 2016, the Chinese government dealt with “loans for nude scams”, which involved lending entities demanding nude photos from female college students as loan collateral. They would threaten to release the images should the students fail to pay up. Such tactics led to untold anxiety, depression, job loss, unemployability, and damaged reputations.

The above examples, highlight how unhibited access to the user’s information allows these Apps to affect other parts of the user’s social life for example. This is a huge cause for concern that should not be allowed to continue unchecked.

Solutions

There is need for changes to be made to counter the current predatory practices of mobile lending Apps.

The restriction of existing regulatory frameworks to traditional lending service providers contributes a certain extent, to the proliferation of lending Apps.

Policy changes are needed to ensure that the processing of personal information is in line with universally accepted data protection principles.

In our report, we noted that protecting the human right to privacy should be an essential element of fintech.

One way to achieve this is by restricting the amount of data collected by these Apps to what is necessary for the purpose of determining the outcomes of loan applications.

Additionally, any data collected by the Apps should only be collected with the full and informed consent of the person using the App. Informed consent is only possible in instances when there is transparency in the type of data that is collected accompanied by clear information on why that data is collected and the circumstances under which it will be processed and subsequently stored or erased.

There is a need to put in place accountability measures that apply when the service providers that run these loan Apps contravene data protection laws and policies. Accountability means that service providers are held liable for any negligent abuse of a data subject’s privacy and data protection rights.

These Apps should only be allowed to process data when such processing is attended by fairness. Fairness requires that the data subject’s right to dignity be at the forefront of decisions to access data or to use that data in a certain way—for example, during the debt or loan recovery stage of the process.

Moreover, apart from the data protection component of how these Apps operate, there is also need to ensure that current national and international privacy regulations are applicable to fintech.