How a company illegally exploited the data of 14 million mothers and babies

If you’re in the UK you may know Bounty as the company that distribute packs of samples to pregnant women at midwife appointments. They’re also the ones that were found to have illegally shared the data of over 14 million mums & babies with 39 companies.

-

In April 2019, Bounty were fined £400,000 by the UK’s data protection authority for illegally sharing the personal information of mums and babies as part of its services as a “data broker” between 1 June 2017 and 30 April 2018.

-

Bounty collected personal data from a variety of channels both online an offline: its website, mobile app, Bounty pack claim cards and directly from new mothers at hospital bedsides.

-

It remains unknown whether and how the data that Bounty collected and shared is continued to be used to profile and target those 14 million mothers and their babies today.

-

We will continue to uncover data broker abuses and hold the companies to account and we will continue to advocate for the privacy of women accessing reproductive and maternal care to be upheld.

Image found here.

Founded in 1959, Bounty UK Limited markets itself as an information service for pregnant women and new mothers. Prior to the pandemic, it was best known for distributing “Bounty packs” of free samples of baby products to pregnant women at midwife appointments, to new mothers on maternity wards in the UK and through its digital presence via its website and app. Bounty representatives also sold new born photography packages to new mothers at the hospital bedside. Bounty entered “distribution” and/or “photography” agreements with, they claim, over 175 hospitals in the UK, which means the Bounty representatives had access to maternity wards, allowing them to approach new mothers shortly after they had given birth.

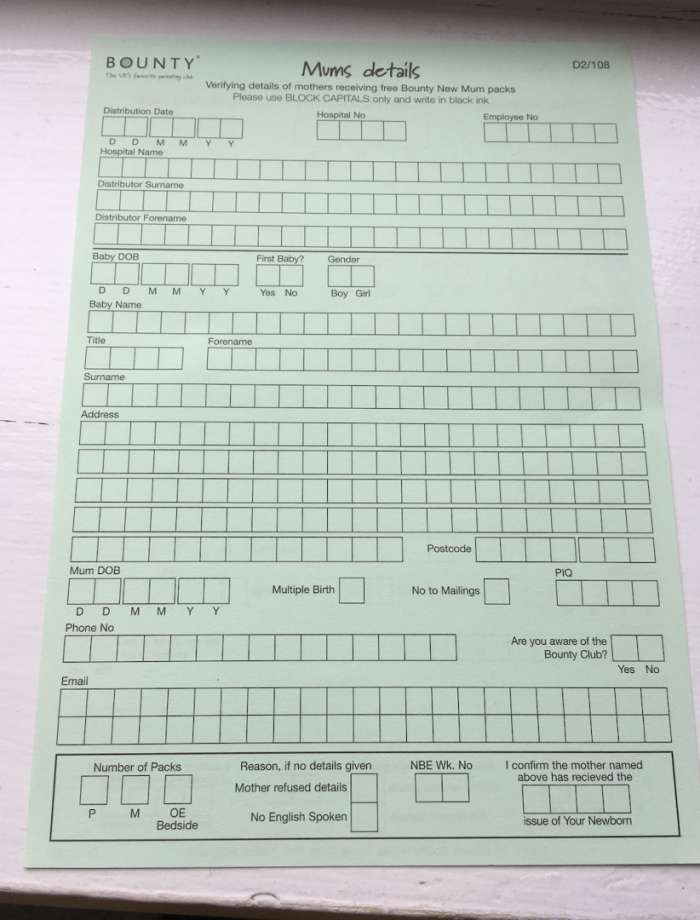

Bounty collected personal data from a variety of channels both online and offline: its website, mobile app, Bounty pack claim cards and directly from new mothers at hospital bedsides. In maternity wards, new mothers were asked to complete paperwork describing themselves and their baby. Specifically, from the new born, the company collected the name, date of birth, and gender. From the mother, Bounty collected the name, date of birth, address, email address, place of birth, if the mum speaks English, and if the birth was their first.

By March 2020 the UK was heading into lockdown due to the spread of coronavirus. Bounty representatives appear to have stopped entering maternity wards and in November 2020 the company reportedly went into administration. However, the company does maintain its online presence and still operates certain parts of its business under a new legal entity. Their website indicates the intention for Bounty representatives to return to maternity wards once Covid restrictions lift.

Harm

Over the years there have been high profile complaints about Bounty’s access to the UK’s maternity wards. Invasions of privacy and hard selling tactics at the bedside are reported repeatedly by distressed new mums. There are many reports of women approached within hours of giving birth, still bleeding and trying to breastfeed, sleep, or recovering from birth trauma. From these reports, many felt pressured into handing over their personal details or buying photography packages they couldn’t afford. One new mother was approached when her baby was fighting for their life in intensive care. There is a horrific report of a mother approached after her baby had tragically died shortly after birth.

In April 2019, Bounty were fined £400,000 by the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) for illegally sharing the personal information of mums and babies as part of its services as a “data broker” between 1 June 2017 and 30 April 2018. A data broker is a company that collects, buys and sells personal data - your personal data. Bounty has expressed regret that they shared “some” personal information with “a small number of data brokerage companies”. The ICO found that the personal information of over 14 million mothers and babies were shared with 39 companies. The ICO judgement only names the four largest recipients of personal data - the credit reference agency Equifax and the data broker Acxiom (who in turn sell personal data on to others), along with Indicia and Sky. The remaining 35 companies remain unnamed. The investigation also found that Bounty shared the data with these companies without telling the mothers that they would do so.

Alongside its decision, the ICO said “The number of personal records and people affected in this case is unprecedented in the history of the ICO’s investigations into data broking industry and organisations linked to this.”

“Bounty were not open or transparent to the millions of people that their personal data may be passed on to such large number of organisations. Any consent given by these people was clearly not informed. Bounty’s actions appear to have been motivated by financial gain, given that data sharing was an integral part of their business model at the time."

The ICO went on to say: “Such careless data sharing is likely to have caused distress to many people, since they did not know that their personal information was being shared multiple times with so many organisations, including information about their pregnancy status and their children.”

It remains unknown whether and how the data that Bounty collected and shared is continued to be used to profile and target those 14 million mothers and their babies today.

Solution

The Bounty case is unusual as data brokers are often companies people have never heard of. Rarely are they public facing companies or household names that provide other services. Data brokers usually exist behind the scenes and opaquely collect vast amounts of information about what people do online and off.

Given the nature of the industry and our understanding of how data brokers work, the personal information of those 14 million new mothers and their babies collected by Bounty in 2017-2018 and shared with 39 companies may be sold and resold many times over, with little certainty as to who it is sold to and what it will be used for.

In fact, Paragraph 46.2 of the ICO decision states that Bounty, “…tracked the data it shared, trading data up to 17 times in a 12-month period…”, which it found “arguably disproportionate, and opened the affected individuals to excessive processing that they did not consent to”.

What is missing from the ICO’s assessment and Bounty’s response is recognition that there is a person behind each of the pieces of information that was sold and traded. A person who does not know if they are part of the 14 million, what information has been traded, where their data is now and what it is being used for. A person who deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. A person who is powerful and has rights to locate that data and have it deleted, but to do so needs to know where it is.

Anyone can exercise their legal right to ask Bounty to tell them if their data was shared to one of the 39 companies. By sending Bounty a data subject access request, women are able to ask for this information, and PI has a guide on how to do so here. However, it doesn’t stop there. Each of the 39 companies would also need to be contacted separately to ask if they still have that data and whether they themselves shared it with other third parties and ask that every single one deletes the data. It’s an uphill battle, one that PI experienced in our investigation to find out how advertisers on Facebook obtained our personal data.

In general, if people are unaware that their data is being sold on, they are unable to properly agree or disagree to such data sharing. It is for these reasons PI believes that the entire industry is out-of-step with modern data protection and privacy laws - and it’s time for the industry to be killed off.

In 2018, PI filed complaints against seven data brokers and ad tech companies (a catch-all term that describes tools and services that connect advertisers with target audiences and publishers) to data protection authorities in the EU and UK, including against Equifax and Axiom (two of the companies Bounty were found by the ICO to have sold personal information to). Since then, data protection authorities in the UK, France, and Ireland have opened investigations into several of the data broker and ad tech companies as a result of PI’s complaints.

Finally, it is clear that sales and marketing companies should not be able to access maternity wards. This does not happen on any other hospital ward. Can you imagine coming round from major surgery to find a stranger at the end of your bed trying to sell you something?

Accessing reproductive and maternal healthcare should not require people giving up their human rights, including the right to privacy.

What’s next

The ICO’s decision named only the four largest recipients of the data collected and shared by Bounty. One of these companies was Sky - Bounty provided Sky over 30 million records.

In 2021, PI wrote to Sky to ask what actions they had taken to locate the data received from Bounty and whether they deleted it, if they had attempted to notify any affected people, or if they had changed their internal policy or practice with regards to receiving third-party data.

Sky refused to answer PI’s questions, saying “due to both passage of time and the confidential nature of the information being requested, we are not able to respond to your questions”.

PI will continue to uncover data broker abuses and hold the companies to account, and we will continue to advocate for the privacy of women accessing reproductive and maternal care to be upheld.