How digital health apps can exploit users’ data

Digital health apps of all kinds are being used by people to better understand their bodies, their fertility, and to access health information. But there are concerns that the information people both knowingly and unknowing provide to the app, which can be very personal health information, can be exploited in unexpected ways.

- Apps that support women through pregnancy are one example where data privacy concerns are brought sharply into the spotlight.

-

Reproductive health information is highly sensitive, and the implications of services which do not respect that fact can be serious.

-

Apps that are taking on the responsibility of collecting that data, need to take it seriously - but as PI has repeatedly found, many don’t.

This piece is a part of a collection of research that demonstrates how data-intensive systems that are built to deliver reproductive and maternal healthcare are not adequately prioritising equality and privacy.

Digital health apps of all kinds are being used by people to better understand their bodies, their fertility, and to access health information. But there are concerns that the information people both knowingly and unknowing provide to the app, which can be very personal health information, can be exploited in unexpected ways.

Apps that support women through pregnancy are one example where data privacy concerns are brought sharply into the spotlight.

There are more pregnancy apps than for any other medical topics. And there is some evidence that apps may be a useful part of maternal and reproductive healthcare. For example, an app used as part of a larger telehealth intervention was found to improve asthma control in pregnancy and another found that one smartphone-based reminder system was helpful in the management of post-natal urinary incontinence.

However, these apps were both part of specific studies and specifically designed medical interventions. That’s not true of most of the apps that you might come across in the wild, nor of the increasing number of apps that are being developed and released by private companies, charities, even by the UN.

A Wired report revealed that pregnancy apps have serious content and disinformation problems, but they don’t stop there – PI has found persistent problems with apps, including reproductive cycle apps, data sharing practices, and even with basic access to certain apps.

PI has conducted its own research into data privacy and smartphone apps before. For example, when we looked at some of the most popular apps in the world, we found that 61% transferred data to Facebook the minute the user opened the app. When we turned our attention to menstruation-tracking apps, we found that many of the companies we looked at did not take adequate precautions with the health data that people enter into the apps. In fact two shared extensive and deeply personal sensitive data with third parties, including Facebook.

Apps that track women’s fertility cycles and provide reproductive health information have proliferated over the past few years. The Flo menstruation app alone has a global user base of 200 million.

Apps like Flo aim to give users visibility into their menstrual cycle, apps that aim to take the place of or complement contraception, apps that aim to give people heightened visibility into their fertility, apps that give you information on your foetus’ development, and beyond.

So what data privacy protections are these apps and the companies developing them putting into place to protect the oftentimes very personal information users entre into the app? And what sort of data are these apps collecting, without users necessarily being aware?

It’s not a surprise that the proliferation of reproductive health apps has reportedly resulted in some apps providing subpar content. It has been reported that some of the pregnancy apps you are most likely to find in the wild have a serious content problem. A recent Wired investigation found them to be “a fantasy-land-cum-horror-show, providing little realistic information about the journey to parenthood. They capitalize on the excitement and anxiety of moms-to-be, peddling unrealistic expectations and even outright disinformation to sell ads and keep users engaged”. Even saying that “they are yet another way the internet and America’s health care system are failing pregnant people”.

Many of the currently available apps are created by companies who exist not to support pregnant people, but rather to make money. And one way to make money from apps is to collect and share or sell user’s personal data. 72% of the apps reviewed by one study did not cite any actual medical literature at all.

Nina Jankowicz, the disinformation researcher who wrote the wired report, found this to be the case in her research. For example, one of the apps she gave her email address to, a mandatory step to access the app, subscribed her to emails from “Pottery Barn Kids”, from which she couldn’t unsubscribe from. This could mean that Nina’s email and other information about her, which she is not aware of, was shared with Pottery Barn Kids and potentially others as well.

Below we have looked at two reproductive health apps to understand potential concerns arising from how they treat user’s personal data and the overall design of such services.

Badgernet

Badger Notes is a UK maternity app that allows women to view their medical notes, self-refer to the maternity department, and more.

Badgernet is intended to form part of the maternity care process: it forms part of the maternity care pathway and is used both by doctors and patients. It includes the Badgernotes app, which allows a person to see their future appointments, postnatal notes, and a summary of the baby’s care and more.

It’s designed to be used by both a maternity care team and pregnant women. It is directly involved in the provision of medical care. As of 2018, Badgernet was being used in 250 hospitals around the UK.

In 2018 Clevermed - the company which owns and operates Badgernet - were surprisingly candid about the risks of their system.

When they were using an older broadband solution, their managing director Peter Badger said:

“We would have situations where we had to do a national system update, which involved downloading about 50MB to 10,000 workstations at once, and it would flat-line the bandwidth for three or four hours at a time, and nobody could select a patient to view until everybody had downloaded the updates.”

According to a 2018 report by Computer Weekly: “In that three- to four-hour window, clinicians were unable to access patient records. In an acute obstetric scenario where, for example, this data might be vital in determining whether or not to deliver a baby via an emergency caesarean section, this could result in unforeseen challenges for the clinical team, and potential risks to the patient.”

That’s a terrifying potential consequence of a platform like Badgernet. Though the limited bandwidth of the NHS’s old broadband system has since been upgraded, the fact that updates to the Badgernet platform might have put women and their babies at risk is a concern.

Another potential concern with Badgernet is that the platform can hold very personal information about people.

The information shared with Badgernet is health information, which is a special category of data under UK law and requires extra protections.

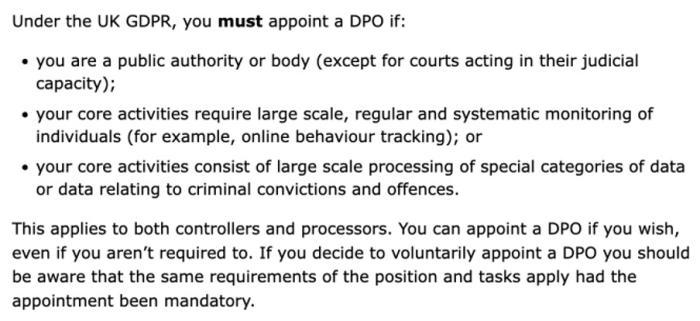

The ICO explain on their website that a DPO must be appointed if your core activities consist of large scale processing of special categories of data like health data.

Arguably, this covers Badgernet and thus Clevermed. However, at the time of writing, neither appear to have a data protection officer listed on their websites or a data protection email anywhere. A data protection officer is an important role - but it’s not clear (from their website or their Linkedin) whether Clevermed has a person in this role.

Badgernet’s privacy policy also raises some concerns - it says:

"If you wish to receive push notifications you will need to enable your notification settings on your mobile device. Push notifications are managed by our Microsoft Notification Hub in the UK; this service has access to a unique device/user identifier but to no other personal identifiable information. From time to time you may receive service messages solely for the purpose of administering the application.

For Android devices, Microsoft Azure sends push notifications via Google Firebase. Firebase will store data in Google Analytics for reasons such as improving Google products and services."

What this means is unclear. How much data about each notification - which could be an appointment reminder or maternity care message - is being passed to Microsoft and Google, what is being stored, and whether that data is attached to a unique device identifier is unclear. While notifications such as “upcoming midwife appointment at hh:mm”, or “access your ultrasound results” are not personal data on their own, depending on if and how they are tied to a unique identifier which can be easily traced back to an identifiable individual, they may disclose information from which personal data could be inferred. Users should always understand where their data is going and why. But here Badgernet does not seem to be providing that level of information to its users.

Another concern is that the roll out of these apps is around people’s ability to access such apps. Not everyone has a digital device, and not everyone has a recent smart phone.

Part of Badgernet’s offer is to allow women to self-refer to their local maternity unit through the app or website. While most NHS units still allow users to call to self-refer, or to go through their GP, the risk with any digital service is that is becomes the default, pushing the offline mechanism to the side as it receives fewer and fewer users, and creating a poorer service for those who have no other option.

Similarly, Badgernet is supposed to allow for the replacement of paper records throughout the entire maternity process - one NHS trust even says that “By June 2022, all expectant parents should be using the ‘Badger Notes’ app and portal.”

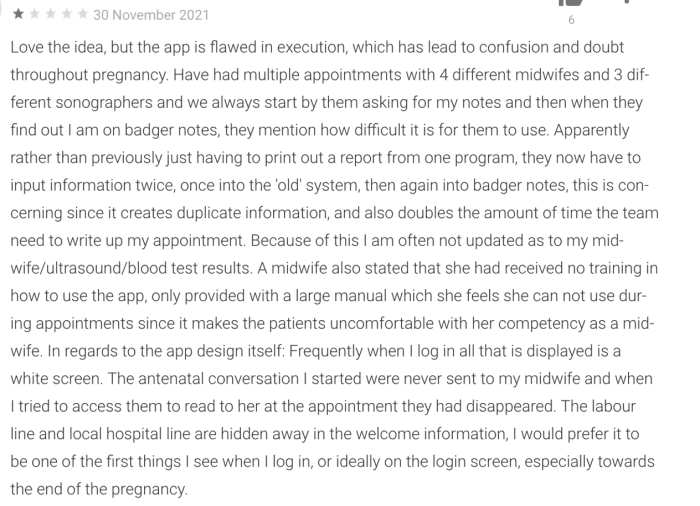

This is likely impossible. And it would mean that, for patients without the appropriate digital access, care teams will have to double enter data, creating a paper record for those families to use.

Again, any system which singles out marginalised parents, and creates extra work for the care team to accommodate them, could well lead to a poorer experience for that family.

User Experience

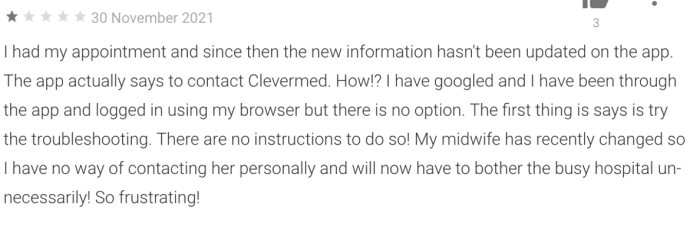

A final concern with Badgernet is the apps’ apparently poor user experience. Users are excoriating in the reviews deemed ‘most relevant’ by Google in the Google play store.

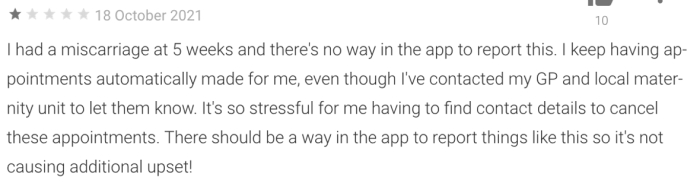

In one review from 2021 a woman explains that she had a miscarriage but the app persistently made appointments for her that she persistently had to follow up and cancel.

It should be noted that, overall, on Google Play Badgernet has 1,320 reviews and an average 4.4 star rating.

And on the Apple store they had 3400 reviews, with an average 4.4 out for 5.

We thought it was relevant to include the reviews of these apps to point to the risks and flaws that can happen in these systems – all technology breaks sometimes, and this is a higher risk system.

Even if the app doesn’t work for a small percentage of people (which increasingly doesn’t seem to be the case here) is it reasonable for the health services to pay for and push a system which, for example as above, incessantly provides a user with irrelevant health information?

Grace Health

Grace Health is an AI chatbot based in Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya - with partnerships with pharmacies and with Marie Stopes Ghana (MS Ghana).

The AI chatbot Grace Health can be delivered either through an app or through Facebook. It responds to people’s questions and tries to connect them with relevant information, and - in Accra, Ghana, where they have relevant partnerships - it allows users to order medication from a pharmacy through a partnership with Mpharma.

Grace Health has received some funding from academic institutions, has commercial partnerships with pharmacies, and a partnership with Marie Stopes Ghana. For the latter, the chat bot refers users to MS Ghana if they want to talk discuss their options with regards to a new pregnancy.

The first thing that should be noted is that, while Grace Health acknowledges that “with a stigmatised and sensitive topic like sexual and reproductive health, safety and security concerns become highly relevant in order for women to dare to take advantage of the content available” there is simply no way currently to have a truly private conversation on Facebook.

Any woman using Facebook chat to ask sensitive medical questions to the Grace Health chat bot on Facebook is having their information shared with Facebook, including whether they have been referred to MS Ghana for information about their reproductive choices.

That is due to the design of Facebook – and Grace Health’s choice to provide their bot on Facebook’s platform. Conversations on Facebook haven’t been end-to-end encrypted, though that may soon change.

One of the things Grace Health has tried to do is introduce nicknames, so users don’t have to share “any identifiable information when chatting with Grace”. Again this simply isn’t possible on Facebook. Even if a user created a ‘fake’ account against Facebook’s terms of service, Facebook can still access information about them, their devices, and their location.

This is likely also true for a user using the app, even if they did use a nickname. Devices have unique identifiers, and it is not clear what, if any, information Grace Health collects from its users through its app.

However, the Grace Health app permissions include access to:

Phone

read phone status and identity

Photos / Media / Files

read the contents of your USB storage

modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Wi-Fi connection information

view Wi-Fi connections

Device ID & call information

read phone status and identity

Storage

read the contents of your USB storage

modify or delete the contents of your USB storage

Other

receive data from Internet

control vibration

view network connections

full network access

prevent device from sleeping

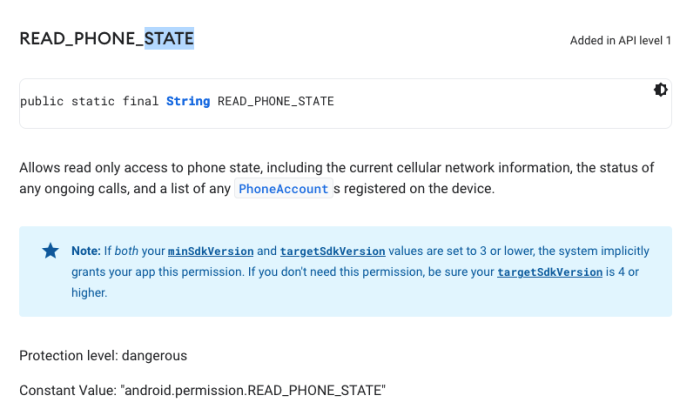

Some of these, such as ‘read phone status and identity’, ‘full network access’ and ‘view network connections’ are particularly troubling. For example ‘Read_Phone_State’ is an Android permission that Android mark as ‘dangerous’ and it’s not clear why Grace Health would need that information.

Grace Health are absolutely right that sexual and reproductive health are highly sensitive topics and need a sensitive approach to security and privacy. But it’s not clear if Grace Health are truly limiting the amount of data they collect or being entirely forthcoming with their user base. Suggesting that a nickname means that a user “doesn’t need to share any identifiable information when chatting with Grace” would seem to be misleading.

Grace Health’s terms of services also raises a further concern:

“Further, you grant the Company, a royalty-free, perpetual, irrevocable, sublicensable, assignable, non-exclusive right (including any moral rights) and license to use the User Content in anonymised or aggregated form for commercial and research purposes. Such right include the right to reproduce, modify, publish, translate, transmit, create derivative works from, distribute, derive revenue or other remuneration from, perform, and otherwise use any such User Content (in whole or in part without the use of your name) worldwide and/or to incorporate the User Content in other works in any form, media, or technology. Note that we respect your integrity and will not use the User Content in any way that may identify you as an individual.”

This is all the information Grace Health give in their terms of service. Even if the data is thoroughly anonymised and can’t be connected to the individual who gave it to them, that doesn’t mean users don’t deserve to know what’s happening to it.

Grace Health don’t say who they may sell this data to or how they might otherwise derive revenue from it, how they may reproduce it or publish it, or what it means to create derivative works from it.

By the current wording you could find your situation reprinted in anything from a magazine to a romance novel. Anonymity is good, but transparency is vital.

Furthermore, anonymising data is hard. And Grace Health’s description - that they can use your user content “in whole or in part without the use of your name” is worrying. We would hope they are taking significant further steps to anonymise any user data or content before doing any of the things they have listed here. We can’t be sure if that’s true, however, as Grace Health don’t provide full transparency.

Grace Health want users to trust them, and yet there is very little publicly available information to users as to what data is collected, for what purpose, who it’s shared with and what safeguards are in place to protect their data and identity when they decide to use and share this information. Transparency would be a good first step to making that trust a reality.

Ultimately, these are just two apps, but they raise a wide range of concerns that have persistently popped up in this marketplace. Reproductive health information is highly sensitive, and the implications of services which do not respect that fact can be serious. Apps that are taking on the responsibility of collecting that data, need to take it as seriously - but as Privacy International has repeatedly found, many don’t.