IMSI Catch 22: Understanding The Role Of Spying Equipment In The Mi Sangre Case

The use of IMSI catchers[1] to arrest individuals is rarely documented — as IMSI catchers are used secretively in most countries. The arrest of Colombian drug lord Henry López Londoño in Argentina is therefore a rare opportunity to understand both how IMSI catchers are used, and also the complexity of their extraterritorial use.

In October 2012, Londoño — also known as Mi Sangre (“My Blood”) — was arrested in Argentina. His arrest was the result of cooperation between the Dirección de Investigación Criminal e Interpol (DIJIN, the criminal investigation division of the Colombian police), the Argentinian intelligence services (Secretaría de Inteligencia del Estado, also known as SIDE, at the time) and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), a US law enforcement agency. While fighting extradition to the US, Londoño made the case that an IMSI catcher had been used illegally as part of his arrest.

Hunting Down Londoño

After six months of being hunted down, Londoño was arrested on 20 October 2012 in a restaurant in Buenos Aires, the city where he had been hiding since December 2011. What eventually betrayed him was a phone call to his wife, during which he told her not to wait for him as he was having a business lunch at the restaurant Fettucine Mario. The police were there to greet him.

Immediately after his arrest, the US requested his extradition, where he was wanted on drug smuggling and conspiracy charges. But the request was followed by four years of legal proceedings, as Londoño’s lawyers argued their client would not be safe in the US, and Londoño was only extradited on 17 November 2016.

During those four years, Londoño’s lawyers also argued an IMSI catcher was used illegally as part of his arrest.

There is currently no explicit legal framework regulating the use of IMSI catchers in Argentina. While journalists who have reported on the case have referred to IMSI catchers as being prohibited in the country, there is no law that explicitly prohibits the use of these devices.

The Smuggling of an IMSI Catcher

On 27 April 2012, Argentinian judge Norberto Oyarbide authorised a team of Colombian police officers to enter the country and track Londoño. According to Argentinian publication Diario Veloz, the Colombian police asked for permission to use equipment that would allow them to locate Londoño’s phone but indicated that the equipment could in no way be used to hear or record phone conversations or messages.

On 30 May 2012, Oyarbide received a phone call from Jaime Stiuso, who was at the time the head of the powerful Argentinian intelligence service SIDE (dismantled in February 2015 after a political scandal that took place 2 months earlier). Stiuso informed Oyarbide that an IMSI catcher was being used by the Colombians and clarified that the tool could intercept the data and calls of anyone in its vicinity. The day after, Oyarbide ordered the expulsion of the Colombian policemen. The IMSI catcher, on the other hand, did not leave Argentina.

According to documents obtained by Diaro Veloz, the IMSI catcher had in fact been brought to Argentina by two Colombian spies, Diego Hernán Rosero Giraldo and César Gonzalo Triana Amaya, on 10 April 2012. That date precedes the date Colombian police even requested permission to enter Argentina. Documents available online reveal that in June 2012 the two spies received an honourable decoration for “distinguished service to the country and to society, outstanding for their sacrifice, perseverance and dedication in the fight against crime.”

Name: Stingray. Function: Intercepting Communications

Privacy International obtained a confidential legal document (see annex) from April 2013 pertaining to the case between Argentina and Colombia. The document is a technical concept written by the Colombian forensic company Adalid. It was ordered by a government to explain to another government the use of a model of IMSI catcher called “Stingray” from the company Harris Corporation. The document was shared with us by a source close to the case and we believe the document to have been ordered by Colombia for submission to the Court in the case brought by Argentina.

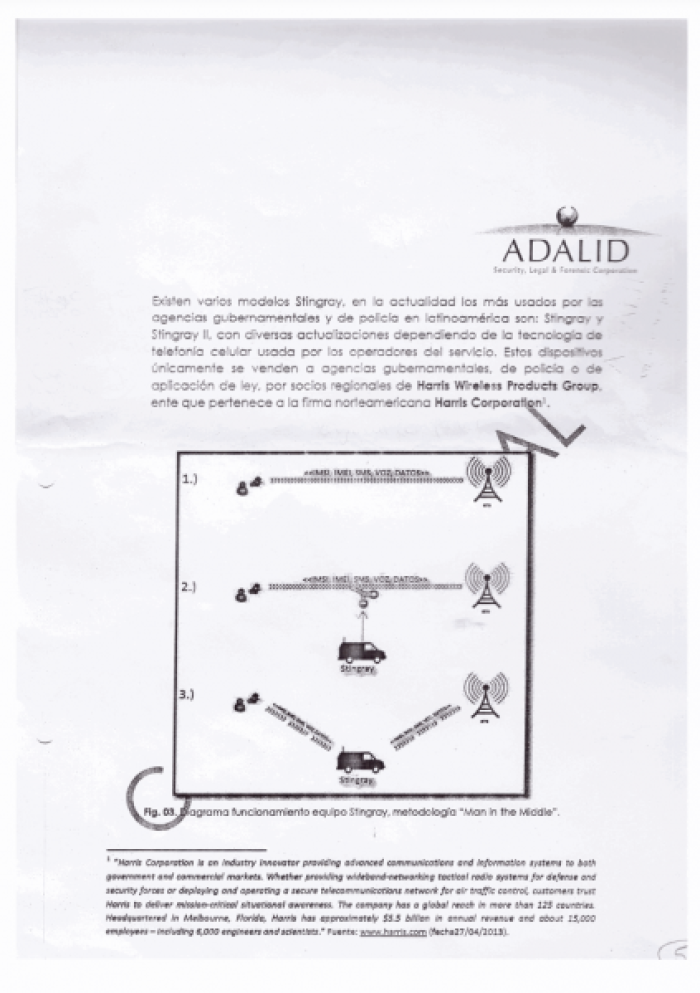

The document details what IMSI catchers are and more specifically how the Stingray model of IMSI catchers function. The technical concept describes the components of the Stingray and how to conduct a “man in the middle attack” in order to intercept the content of communications. Indeed, while not all IMSI catchers can intercept communications, as we mentioned above, this particular model offers this capability. The document clarifies that Stingrays can only be sold to government agencies. The device has a range of action of 500 metres.

Revealing The Conclusions

While the conclusion of the legal case — led by judge Claudio Bonadio — between Colombia and Argentina remains unknown, this story illustrates the importance of the need for clearer and stricter legislation on IMSI catchers. It is indeed very concerning that Colombia could ask for an authorisation to track Londoño’s phone without clarifying very specifically the type of equipment they were planning on using. IMSI catchers are too often dismissed as a tool of targeted surveillance, when in fact it is equipment — as the Argentinian intelligence services realised — that could be used to indiscriminately surveil any one in its surroundings.

It is equally concerning that Colombia may have brought the IMSI catcher into Argentina and begun deploying it even prior to requesting authorisation. This type of extraterritorial action — without Argentina’s prior consent — raises a number of troubling issues. On the Colombian side, who authorised its spies to use an IMSI catcher and under what law? Did that authorisation include extraterritorial action in Colombia’s territory? Did Argentina perceive such action to violate its sovereignty? Why did Colombian police later request authorisation to use the same device in Argentina’s territory?

Privacy International has been challenging the use of IMSI catchers, which are increasingly used in many countries despite the complete absence of regulation. In the UK, for instance, while we have evidence of their use, the government even refuses to acknowledge their very existence. We hope this story will be a lesson to governments who have been dismissing the importance of transparency around the use of IMSI catchers: it is now time for the government to reveal the conclusion of their investigation on the case and establish strong regulations on the use of IMSI catchers.

Privacy International Recommendation to the Argentinian Government:

Publish the conclusion of the Bonadio investigation into the use of IMSI Catchers in Argentina by Colombian police, particularly the conclusions relating to the likelihood of interception of Argentinians’ private information as a result of the use of IMSI Catchers.

This piece was authored by PI Research Officer Eva Blum-Dumontet.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

[1] An IMSI catcher is a portable surveillance equipment that allows the “off-the-air” interception of data (phone communications, messages, location data) from phones in its surrounding environment. In order for a mobile phone to function it has to communicate with a cell tower (Base Station, BTS). The phone chooses the best cell tower to connect to based on the strength of the signal. An IMSI catcher presents itself as the most powerful cell tower in a given area, so that the phones in the surrounding area connect to it instead of an actual cell tower. Once connected to the IMSI Catcher’s base station the catcher has the mobile phone provide its IMSI and IMEI data. Once these details have been gathered it becomes possible to monitor the operation of the phone: the voice calls taking place, the messages being sent and the location of the phone. Not all IMSI catchers however are capable of intercepting communications.