Monitoring the Surveillance Industry: Using data to protect privacy

Often when asked to discuss open data and privacy the objective is to successfully navigate the tension between the fundamental right to privacy, and the virtues of open data. And there is a tension. It is rare to see increased collection of data alongside greater privacy protections. The recently released Surveillance Industry Index (SII) is one of those rarities.

The SII, a joint initiative between Privacy International and Transparency Toolkit, is the largest publicly available database on the secretive set of companies selling surveillance equipment to governments around the world. The surveillance export industry has been involved in selling equipment to spy on Bahraini activists, to bolster Muammar Gaddafi’s regime, and to spy on journalists in Morocco. All of this done by a sector that has historically avoided scrutiny of their actions.

For many years, Privacy International attended trade shows where surveillance companies gathered to advertise their equipment to government representatives. At these trade shows, Privacy International covertly collected surveillance company brochures which contained detailed information of surveillance products. Online, these companies prefer to keep quiet and anonymous, with websites that are often opaque labyrinths of marketing buzzwords lacking useful information. Collecting the brochures was important in order to set a benchmark, and increase public understanding about the breadth of the industry.

The same day SII went online, Privacy International also released the Global Surveillance Industry — a report benchmarking the surveillance industry using company data, and technology data gathered by Privacy International during both desk-based research, and field work at trade shows. SII and the report also included transfer data for the first time, which have only recently been made available by various governments around the world. This transfer data was compiled from publicly available data about the sale and exports of surveillance technology. These data sources included official government datasets, media reports, NGOs, research institutes, and, in some cases, technical research like the kind carried out by Citizen Lab, an interdisciplinary lab based at the University of Toronto, Canada.

Recently, there has been success in achieving controls on the export of surveillance technologies. For example, in certain circumstances before a company can export their equipment, the company must approach the export control authority in their country to get the export approved. With this process comes data on the trade of surveillance technologies. Access to this data has opened up a new area of research for journalists interested in working with data to better understand the nature of state surveillance, and those companies that meet the demand for more surveillance power. At the moment, the United Kingdom and Switzerland are the only countries with transparency policies for transfer data; but in time, through pressure from civil society and others, it is expected that more countries will follow.

As Privacy International and Transparency Toolkit launched SII, it was also revealed that the UK had approved over 100 licences for the export of “off the air” mobile phone monitoring technologies to countries such as Indonesia, Turkmenistan, Bangladesh, and China. Often this data is muddled, badly recorded, and misleading, but having set of clear criteria for categorisation on SII meant that journalists could sort through it more easily.

Though still in its infancy, the same data has helped to provide context and improve background reporting. The recent coverage of the Israeli firm NSO Group, revealed by Citizen Lab to be behind the targeting of a UAE Human Rights Defender with powerful malicious software targeted at iPhones, was supported by the NSO Group’s entry on SII.

And it has provided conclusions to leads its generated. The earlier story on approved licences for “off the air” mobile phone monitoring equipment inspired Vice to generate a Freedom of Information request to learn more information about those approved licenses. The response, while helpful, continued to withhold information such as product descriptions. But the product names that were included in the response could be cross checked with product names in the SII database, providing brochures and descriptions of technologies. From those descriptions, the journalist was able to unpack and better understand the type of technology transferred, and the potential effects it may have in the countries to which they were transferred. Vice also went on to publish the entire dataset for further research.

With this information, a lot can be done to better understand privacy issues around the country. What do 14 approved 5a0001f licences, the category which defines the control of “software replicating controlled telecommunications equipment”, mean for Indonesian activists? At first glance, a lot more research is needed for it to become useful.

Let’s see how SII would be able to assist by walking through the kind of data that is available.

The cell that contains good description for the 5a0001f category has the recurring term “Marlin”. With this information, you go to SII, type in Marlin and get 5 results.

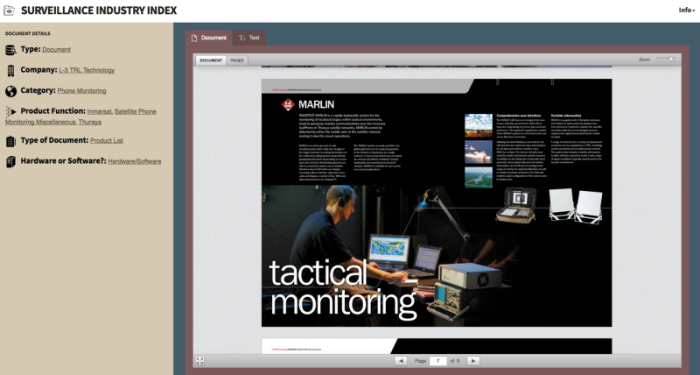

Those responses give you access to documents describing Marlin, a portable monitoring unit for call details and content of messages from mobile phones sold by a company called L-3 TRL Technology.

Further information can then be found by examining L-3 TRL Technology’s entry on SII, which describes their business and provides access to other information products.

Using SII, from the opaque and unhelpful bureaucratic spreadsheet, you now have the makings of a story. This story can be used to campaign in Indonesia, or turned back on itself and reported on to ask questions of the UK Government’s export policies. It can even be used to change the criteria under which a request for a licence to export is assessed, which is what Privacy International are currently working on at the European level.

Even with just this small amount of data, we have gained and shared revealing and useful insights. As we continue collecting data, we will be able to gain deeper insights in the years to come that can be used to assess the effectiveness of regulatory regimes, the trends in trade from the industry, and to block the transfer of technologies to countries with concerning human rights records. But to do this, we will require the insight and intelligence of interested data-driven researchers. SII is just a platform after all.

Explore SII here.