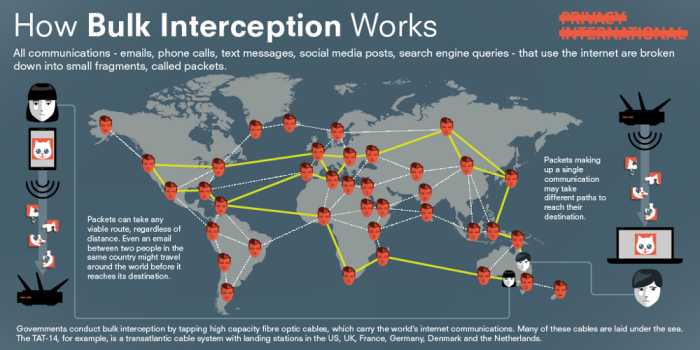

How Bulk Interception Works

This week, Privacy International, together with nine other international human rights NGOs, filed submissions with the European Court of Human Rights. Our case challenges the UK government’s bulk interception of internet traffic transiting fiber optic cables landing in the UK and its access to information similarly intercepted in bulk by the US government, which were revealed by the Snowden disclosures. To accompany our filing, we have produced two infographics to illustrate the complex process of “bulk interception.”

The first infographic describes how communications travel over the internet, which is essential for understanding the mechanics of bulk interception. All internet communications are broken down into smaller fragments, called “packets.” Every packet contains a piece of the content of the actual communication, as well as metadata. Metadata is information about a communication, such as the sender and recipient, the date and location from where it was sent, and the subject line.

Packets that make up a single communication not only take different paths to reach their destination, they can also take any viable route. Distance is not a determinative factor. A communication between two individuals in the same city might therefore travel around the world before it reaches its recipient. The dispersion of packets across the internet means that our communications and data are more vulnerable to interception by foreign governments, who may capture them as they bounce around the world.

The capture of packets, particularly because of the metadata they contain, is intrusive. The internet has dramatically changed the way we communicate and, in the process, enabled the creation of additional personal data about our communications. Metadata is the digital equivalent of having a private investigator trailing you at all times, recording where you go and with whom you speak. But in the digital realm, metadata records even more — for example, your web activity, which could reveal items purchased, news sites visited, forums joined, books read and movies watched. Each of these pieces of data gives insight into an individual. Pieced together, they can allow an intrusive and comprehensive view into a person’s private life, revealing his or her identity, relationships, interests, activities and location.

Mobile digital devices are ever more ubiquitous, generating new forms of data in quantities that continue to grow exponentially. Moreover, the costs of storing data have decreased drastically, and continue to do so every year. Most importantly, the technical means of combining datasets and analyzing this vast trove of data have advanced so rapidly that what were previously considered meaningless or incoherent types and amounts of data can now produce incredibly revelatory analyses. Metadata is structured in such a way that computers can search through it for patterns faster and more effectively and learn more about us than similar searches through the actual content of our communications.

The second infographic breaks down the stages of the bulk interception process. We explain this process further with specific reference to what we know about the UK government’s bulk interception practice.

Interception

The Government Communications Headquarters (“GCHQ”), the UK signals intelligence agency, conducts bulk interception by tapping undersea fiber optic cables landing in the UK. The UK’s geographic location makes it a natural landing hub for many of these cables. The Snowden documents indicate that the UK government — often with the cooperation of telecommunications companies — has attached probes to these cables to intercept their traffic.

Extraction

The probes allow the UK government to redirect a copy of this traffic to buffers, temporary storage spaces, which retain all content for three days and metadata for 30 days.

Filtering

This information is then filtered according to “selectors.” While the common examples provided by the UK government are email addresses and telephone numbers, the full scope of permissible selectors is not known. They could include descriptors as broad as traffic to or from a certain country, particular search engine queries or online purchases, geolocations, or a range of IP addresses. Each of these examples could capture the information of many people.

Storage and Analysis

Intercepted information is stored in databases, which analysts can query, data-mine or use to call up information to examine further. In September 2015, The Intercept published previously unreleased Snowden documents, documenting three GCHQ programs — Black Hole, MUTANT BROTH and KARMA POLICE — which shed light on the ways in which the UK government uses bulk interception of metadata. Black Hole is a metadata repository, storing “email and instant messenger records, details about search engine queries, information about social media activity, logs related to hacking operations, and data on people’s use of tools to browse the internet anonymously.” MUTANT BROTH sifts through Black Hole data related to cookies — which are stored on devices to identify and track people browsing the internet — to monitor internet use and uncover online identities. KARMA POLICE “aims to correlate every user visible to passive [signals intelligence] with every website they visit, hence providing either (a) a web browsing profile for every visible user on the internet or (b) a user profile for every visible website on the internet.”

Dissemination

GCHQ may share intercepted information or the results of analysis to other agencies, such as MI5, MI6 and the National Crime Agency, or governments.

UK Access to US Bulk Interception

The UK government can also access information intercepted in bulk by the US government in various ways. It might have direct and unfettered access to raw intercept material, which it can then extract, filter, store, analyse and/or disseminate. Or it might have access to information stored in databases by the US government, which it can then analyse and/or disseminate. Or it might have access to the US government’s results of analysis, such as intelligence reports, which it can then examine and/or disseminate.

The Snowden disclosures revealed the breathtaking scope of US bulk surveillance. The earliest revelations concerned a program called Upstream, which similarly taps undersea fiber optic cables landing in the US. The geographic location of the US features a high concentration of cables emanating from its east and west coasts. Moreover, the concentration of internet companies in California means that much of the world’s communications — Gmail messages, Whatsapp texts, Facebook posts — will travel to servers in the US in the course of their transmission.

The US government also conducts sweeping bulk interception programs outside of its borders. RAMPART-A, for example, is a National Security Agency (“NSA”) program, operated in conjunction with foreign partners, that aims to gain “access to high capacity international fiber-optic cables that transit at major congestion points around the world.” A leaked NSA document indicates that RAMPART-A can intercept “over 3 Terabits per second of data streaming world-wide and encompasses all communication technologies such as voice, fax, telex, modem, e-mail internet chat, Virtual Private Network (VPN), Voice over IP (VoIP), and voice call records.” MUSCULAR was a program operated jointly with GCHQ, which intercepted and extracted data directly as it transited to and from Google and Yahoo’s private data centers, which are located around the world. According to a leaked 2013 document, in one 30-day period, the NSA sent over 181 million records — consisting of content and metadata — back to data warehouses at its headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland.

The US and UK governments have a long-standing arrangement to share intelligence, particularly signals intelligence, with each other, as well as with Australia, Canada and New Zealand (“Five Eyes alliance”). In 1946, the US and UK governments signed the UKUSA Agreement, a post-war “communications intelligence” sharing agreement, which was later extended to encompass the other three members of the Five Eyes alliance. Part 3 of the UKUSA Agreement states that the “parties agree to the exchange of the products” of certain “operations relating to foreign communications”, including “(1) collection of traffic; (2) acquisition of communication documents and equipment; (3) traffic analysis; (4) cryptanalysis; [and] (5) decryption and translation”.

In some instances, the NSA and GCHQ jointly operate a bulk interception program, as in the example of MUSCULAR above. But the Snowden documents revealed that the UK government also has access to information intercepted through various US bulk interception programs. XKEYSCORE is an NSA “processing and query system,” fed by “a constant flow of Internet traffic from fiber optic cables that make up the backbone of the world’s communication network, among other sources.” As of 2008, XKEYSCORE “boasted approximately 150 field sites…consisting of over 700 servers,” which store “‘full-take data’ at the collection sites — meaning that they captured all of the traffic collected.” XKEYSCORE is accessible to several foreign governments, including the UK, whose analysts can then “query the system to show the activities of people based on their location, nationality and websites visited.”

The UK government also has access to Marina, which is the NSA’s metadata repository. According to an introductory guide for NSA field agents disclosed by Snowden, Marina aggregates metadata intercepted from an array of sources, including bulk interception through the NSA’s fiber optic tapping programs. The guide explains that, “[o]f the more distinguishing features, Marina has the ability to look back on the last 365 days’ worth of…metadata seen by the [signals intelligence] collection system, regardless whether or not it was tasked for collection.”

Conclusion

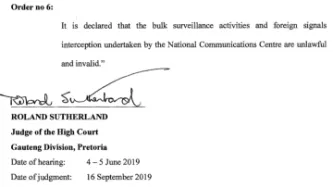

By their very design, the UK and US governments’ bulk interception programs capture the personal communications and data of millions of individuals around the world. Our case represents the first time that the European Court of Human Rights will directly address surveillance on this scale. We ask the Court to find that these practices are fundamentally incompatible with the rights to privacy and freedom of expression.