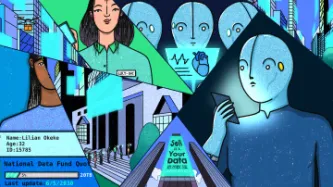

Punjab Government’s Safe Cities Project: Safer City or Over Policing?

By Digital Rights Foundation, Pakistan

What is a safe city?

The answer to this question is not uniform; in fact it varies according to who you ask.

In a focus group conducted by Digital Rights Foundation in May of last year, consisting of women rights activists from across Pakistan, the answer meant imagining a city that was not only safe for women, in terms of their physical safety, but also welcoming for women and non-binary individuals in its architecture and facilities. Women expressed feeling like anomalies when they use public transport, or simply step outside in public spaces.

In another focus group last year, we posed the same question to lawyers and digital rights activists, and they imagined a city without arbitrary roadblocks by law enforcement agencies and over-policing.

Women from lower classes interestingly stipulated economic issues and affordable housing as issues of safety; since there is a clear nexus between safety of a locality and housing prices. Women, outside the exclusive club of the upper and upper middle classes, are often denied access to safe housing simply because they cannot afford it. In conducting a campaign for launch of our report on safe cities, we spoke to individuals around Lahore who imagined a city that was green, walkable, accessible for disabled persons and animal-friendly.

It is important to deconstruct the concept safe city from the bottom-up because the definition is often imposed onto citizens from above, i.e. state institutions. The central question guiding Digital Rights Foundation’s (DRF) situational analysis of the Punjab Safe Cities Authority (PSCA) and its work has been an inquiry into the government’s vision of what a safe city looks like and whether that maps onto the vision citizens hold?

Digital Rights Foundation’s report aims to map and understand the nature and scope of the Punjab government’s Safe Cities project from a human rights perspective. The first phase of the safe cities project was completed in January 2018 with the aim of improving urban policing through ICTs, which saw the installation of 8000 CCTV cameras throughout the provincial capital of Punjab, Lahore, at the whooping cost of twelve billion rupees (almost a hundred million US dollars).

The underlying impulse of the safe cities project has been to ensure safety through digitization of existing policing structures. As we note in the report: “[o]n the surface this is a benign project that seeks to simply digitize and update state machinery to make urban policing more efficient. Nevertheless, the introduction of new technologies does not mark a complete break from the past, rather is a continuation of same policing tactics that were a mainstay of the past.”

We have categorized the project neither as an urban planning scheme, nor an e-government initiative. Instead, the Punjab Safe City Project concerns itself primarily with modernizing policing and “policing culture”. The (flawed) logic there is that our cities would be safer if only they were better policed. Taken at face value, the project aims to eliminate the “thana culture”, a pejorative word used to describe the prevalent abuse of power in the policing system. The modern policing system, aided by technology seeks to bring in transparency, speed and reduce human intervention for corruption. Our report assesses whether the infusion of technology lays to rest these systemic issues within the policing system.

According to our findings, the Authority suffers from many of the same problems that it claims to eschew. There is very little accountability and transparency for the Authority and its operations. Several requests for interviews with its officials were denied on the basis of secrecy. Furthermore, given the scope and ambit of surveillance powers exercised by the Authority, there are no laws or policies regarding data protection. Bizarrely enough, the Safe Cities Authority has been engaging into issues of digital spaces without any legislative mandate.

The operations of the Authority have ensured that safety is guaranteed for large scale events and holidays, where activities can be monitored, controlled and limited. The safety model has not trickled down in terms of everyday crime or reduction of harassment for women in public spaces. Digital Rights Foundation’s report recommends policy interventions in order to make the Authority more accountable and transparent, however ultimately the success of the project will depend on matching its conception of safety with that of their beneficiaries: The citizens of the city it seeks to police.

Our report titled “Punjab Government’s Safe Cities Project: Safer City or Over Policing?” can be found here.