Taking a depression test online? Go ahead, they're listening

Updated on January 2021

Following this research Privacy International submitted a complaint to the CNIL against Docstissimo. Details of this submission as well as the positive changes made by Doctissimo are visible here

This article is part of a research led by Privacy International on mental health websites and tracking. Read our full report.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 25 percent of the European population suffers from depression or anxiety each year, yet about 50% of major depressions remain untreated. This means that everyday thousands of people are looking for information about depression online. They take tests to find out how serious their symptoms are, they try to access resources, or seek information on how best to support a loved one.

Given that the internet is plagued with trackers, whose sole purpose is to collect data to target people with ads, we wondered whether online depression tests are also sharing information about their visitors with others. Privacy International decided to take an in-depth look at the top three depression tests websites in France, Germany and the UK to find out whether the information you provide to these websites are processed securely. Spoiler alert: they are not.

Disclaimer: Our findings of this report show that many mental health websites don’t take the privacy of their visitors as seriously as they should. But shame and silence around mental health problems can be as bad as the problem itself and Privacy International supports campaigns that aim to change the way we all think and act about mental health. Don’t refrain from searching for information about mental health online, or from taking a qualified depression test.

Trackers, trackers everywhere

The first thing we noticed is that the web pages analysed contain a shocking number of third-party trackers. In the case of the French website doctissimo.fr, for instance, the depression test page contacted 48 third parties the moment we opened it. Another example is the depression test of the German site netdoktor.de, which contacted 30 trackers.

Third parties offer additional features that are not necessarily nefarious, such as fonts or analytics. However, our research shows that most trackers are used to collect data about people to target ads at them ever more granular levels. We found trackers from all the large tech companies - Google, Facebook, and Amazon - but also from data brokers, and AdTech companies, such as the native advertising companies Outbrain or Taboola. This is a pattern we have observed at a much larger scale in our research on 136 depression-related web pages.

The key point is this: when a website integrates a third party service or tracker, this third party receives a certain number of information about the user. Typically, this includes the URL of the website they are currently visiting, which in the case of depression test websites almost always includes the words "depression" and "test", as well as information about their browser and device. In many cases, this data is also shared with a unique identifier, which can be stored in a cookie, allowing third parties to track people across the web (and often even across devices) to profile people according to their interests and behaviours.

In practice, this means that countless of third parties know that you are taking a depression test right now.

Online "behavioral" advertising on depression test websites

The fact that depression test websites include marketing trackers is already problematic but we also observed a number of websites that use a particularly invasive technology to serve ads. Netdoktor.de, passeportsante.net and doctissimo.fr seem to use programmatic advertising with Real-Time Bidding (RTB), a practice subject to complaints across Europe and examined in Privacy International complaints against AdTech companies.Through RTB, vast amounts of personal data exchange hands between a large number of players a billion times a day. Any mental health websites that uses RTB could potentially share personal data with thousands of third parties.

For example, Doctissimo.fr share content keyword such as ‘dépression’, ‘déprimé’ (depressed), or ‘quizz’, the page URL (psychologie/tests-psycho/tests-pstchologiques/coup-de-blues-ou-depression), as well as information about the page content (‘psychologie’, ‘test psychologiques’, ‘coup de blues ou dépression ?' with https://europe-west1-realtime-logging-228816.cloudfunctions.net/realtime-logs. These keywords clearly communicate that a user is looking for information about depression and is very likely taking a depression test.

Some online depression tests share your answers with third parties

Among the nine websites we scanned, four shared test answers with at least one third party.

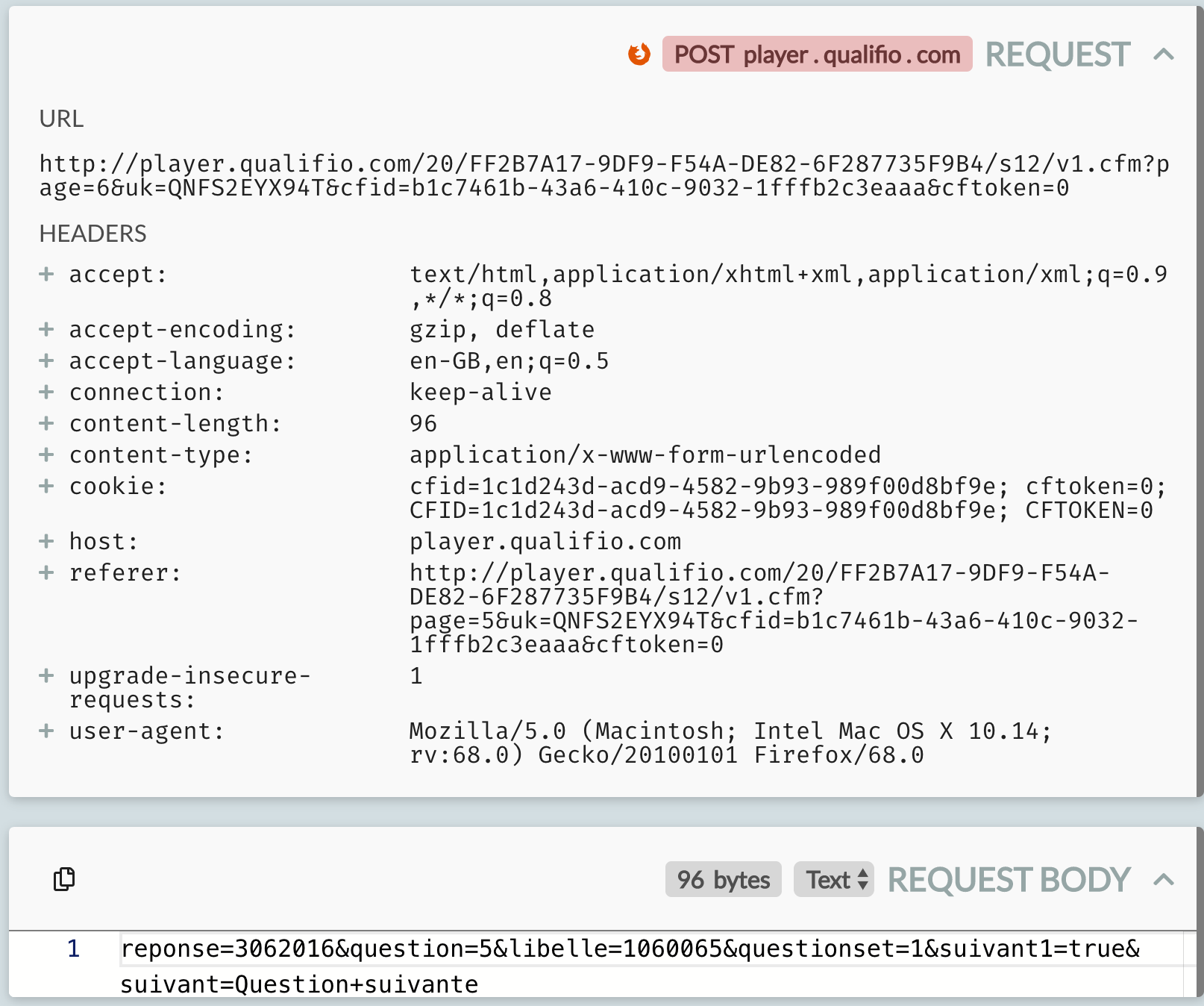

Most notable is the French website doctissimo.fr, which shares test answers as variables and in clear text with a third party. When taking a depression test on doctissimo.fr, answers to the test’s questions are sent to a company called Qualifio. Because Qualifio provides the test form, the company knows the test’s questions, as well as which answer is associated with the response value. Qualifio places a cookie in the user’s browser, which contains a unique identifier. As a result, the answers to the depression test questions that Doctissimo sends to Qualifio, can be linked to a uniquely identifiable individual.

Here is what the POST queries look like:

Note: "reponse" mean "answer" in French.

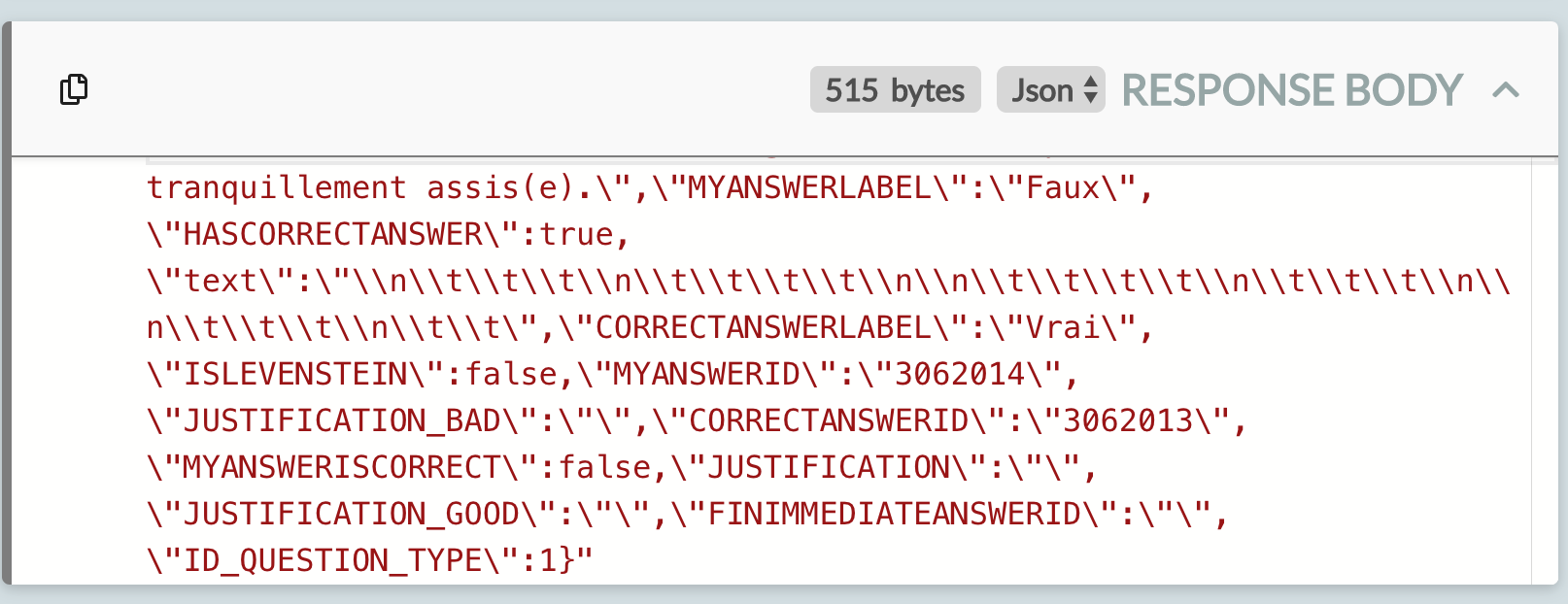

Another example is the GET response that Qualifio sends back to Doctissimo where we can clearly see the question and the answer the user gave.

We also noted that the NHS's mood assessment test shares its URL, the test name ‘Mood self-assessment quiz’, as well as the final test score with Adobe. Adobe’s documentation page for tracking servers suggests that the purpose of this tracking is measurement or analytics, rather than advertising or marketing, even though this is a service that Adobe also offers. When we shared key findings with the NHS, we received the following clarification via e-mail:

“It is not possible to identify any individual from the data collected in the mood self-assessment quiz and no data is shared with any third parties. All analytics data and test scores are linked to a unique, anoymised user ID which cannot be traced back to an individual - it is not linked to an IP address and is randomly generated. In order to ensure privacy of visitors to our website, IP addresses are anonymised.”

The two other websites (passeportsante.net and depression.org.nz) engage in a different kind of data sharing. Instead of sharing the answers to the test with a specific third party directly, test results and test answers are stored as a variable (e.g.: yes = 1, no = 0) in the URL. Given that the URL is part of the default header sent to all third parties (in the referer field), this means that all third parties that are loaded when visiting the page receive all answers to each test question (and in the case of depression.org.nz, the final score of users taking the test). PasseportSanté contacts 41 third-party services when taking the test.

Here's what the URL looks like for depression.org.nz:

https://depression.org.nz/is-it-depression-anxiety/self-test/depression-test/result?q[1]=3&q[2]=0&q[3]=2&q[4]=1&q[5]=3&q[6]=3&q[7]=1&q[8]=2&q[9]=3&priority=16&score=18

We can see the answer to each question ranging from 0 ("not at all") to 3 ("nearly every day"), as well as the final score. In the case of depression.org.nz, this URL is shared with Surveygizmo, Youtube, Google DoubleClick, Cloudfront, Hotjar, Facebook, hap.org.nz and Crazyegg.

We also noticed that the NHS and depression.org.nz test page place a Hotjar cookie associated with a unique identifier. This company provides heatmaps and “session replay scripts” that can be used to log (and then playback) everything you did on a page (scroll, clicks, text typed…). In response to a query by Privacy International, a spokesperson for the NHS DIGITAL explained: "We do not record the session using Hotjars ‘session replay scripts’ when a user starts to complete the ‘mood self assessment quiz’.” (see our report for the full statement)

You often don’t have a choice

Given that health websites can reveal such sensitive data about us we would expect that they are 100% transparent about what happens to your data and give people a genuine choice. Unfortunately, that’s not what we found. We found many websites that don’t ask for user consent before placing a cookie on their browser. We also found websites that ask for consent, but don’t offer a straightforward option to reject consent. The French website doctissimo.fr is a negative example in this regard. The website does not offer a clear option to reject consent and the consent box disappears the moment the user takes any action on the site (such as scrolling). This is interpreted as consent to data sharing with 448 advertising partners, all of which may all process the user’s personal data.

Where things went wrong and how to fix

Our findings show that many mental health websites don’t take the privacy of their visitors as seriously as they should. This research also shows that some mental health websites treat the personal data of their visitors as a commodity, while failing to meet their obligations under European data protection and privacy laws (read our report for an in-depth legal analysis).

Our analysis teaches us three things:

- Consent is optional for many of the websites we analysed, while they should be giving users clear information and a real choice

- There are way too many trackers for advertising purposes on websites about mental health

- Websites sometimes unknowingly share more that they should

Our suggestion to fix this:

- Websites should be transparent about third-party tracking, limit third-party tracking to what is strictly necessary, and obtain valid and informed consent from users by offering them a genuine choice. You should respect their preferences and browser settings, such as DO NOT TRACK, instead of nudging them to consent with annoying and deceptive cookie banners.

- For websites that want to use a select number of third parties, we recommend that they remove the referer header to avoid sharing the webpage currently visited.

- We also recommend that websites that cover potentially sensitive issues, such as mental health, refrain from using programmatic advertising, especially involving RTB, on health-related websites.

- Websites sometimes unknowingly share a lot more data than visitors can reasonably expect. We recommend that websites that offer tests should change the way the results are stored so that they are not shared with any third parties.

As it is our strong desire to present as accurate an assessment as possible prior to the publication of our reports, we reached out to Netdoctor.de, doctissimo.fr, the NHS and PasseportSanté and the the Health Promotion Agency of New Zealand via email. So far, we have only received a response from the NHS. Please read our report Your Mental Health For Sale for a full legal analysis, further evidence and an explanation of the tools and methodology used.