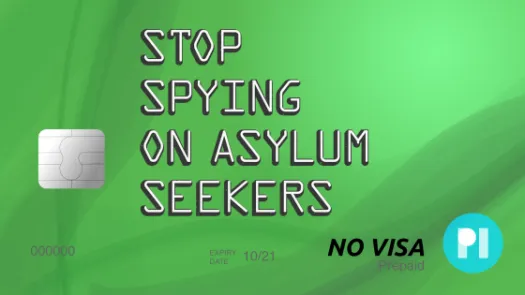

PI intervenes in judicial review to support asylum seekers against the UK Home Secretary’s seizure and extraction of their mobile phones

The Home Office has been seizing mobile phones from migrants arriving in the UK by small boats. Last week, PI intervened in a judicial review at the High Court challenging the lawfulness of this highly intrusive practice.

- PI has intervened in a case against the UK Home Office, challenging their practice of seizing mobile phones of asylum seekers arriving in the UK by small boat in 2020.

- The Home Office admitted that the secret, blanket policy to seize phones was unlawful.

- Looking through someone’s phone, possibly the most extensive and intimate record of their private life, requires serious justification.

- After the litigation started, the Home Office referred itself to the Information Commissioner.

- The case developed in the midst of heated debates around the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, which (amongst other extensive policing powers) gives Immigration Officers powers to extract data from mobile phones of victims and witnesses.

Last week, Privacy International intervened in an important and long overdue Judicial Review into the UK Home Office’s secret and blanket policy of seizing mobile phones of all migrants who arrived to the UK by small boat between April 2020 and November 2020.

The case revealed that migrants were searched on arrival at Tug Haven in Dover and compelled to hand over their mobile phones and provide their PIN numbers. During the course of proceedings it came to light that the Home Office had self-referred itself to the Information Commissioner’s Office for breaches of the Data Protection Act.

The claim was brought by three claimants, represented by solicitors at Gold Jennings and Deighton Pierce Glynn.

The Home Office admitted that the secret, blanket policy to seize phones was unlawful. But substantial issues remained for consideration before the Court, notably whether the seizure, retention and extraction of data from phones breached the European Convention on Human Rights and the UK’s Data Protection Act 2018.

Privacy International’s intervention

Privacy International made written submissions supported by witness evidence, demonstrating the considerable privacy intrusion caused by extracting data from someone’s mobile phone. PI argued in submissions that the Home Secretrary had not discharged her burden of justifying the proportionality of the measure to its objective.

PI’s intervention in the case was built on its years of research and expertise on the practice of mobile phone extraction (“MPE”) around the world, which led it to complain to the Information Commissioner’s Office (“ICO”) in 2018 about police forces’ use of this intrusive technique and its lack of legal framework. This spurred the ICO to investigate and produce a damning report requiring that much stronger safeguards were put in place.

But the evidence presented at the High Court suggests that such safeguards still do not exist.

MPE can give authorities access to all of someone’s phone data - call records, private messages, photographs, data from health apps, personal notes, etc. Most of the time, the vast majority of this data will be irrelevant to an investigation. And yet authorities will download it, sift through it, analyse it, check it against and combine it with other data, and retain it beyond the conclusion of the investigation.

Throughout the hearing, lawyers for the Home Office didn’t once contest the seriousness of the interference with privacy that MPE constitutes, and PI’s evidence remains unchallenged.

Emergencies don’t justify widespread illegality

During the hearing, Mr Alan Payne QC argued for the Home Office that fairness should be owed to the officers who operated the unlawful policy, and that “no one had time to sit down and write a 67-page thesis on the Data Protection Act”.

But you don’t need a 67-page thesis on data protection law to realise that looking through someone’s phone, possibly the most extensive and intimate record of their private life, might be unlawful and requires serious justification. Even dealing with situations of emergency comes with the need to observe strict safeguards and respect for the rule of law.

The Home Office self-referred to the ICO for breaches of data protection law

The case revealed that the Home Office had referred itself in July 2021, months after this case started, to the Information Commissioner’s Office (“ICO”) to alert to potential breaches of data protection law arising from the blanket seizure policy and extraction of data from mobile phones. The Home Office had until today refused to disclose the contents of this self-referral, but the judges ordered disclosure on the last day of the hearing.

For too long the use of mobile phone extraction by the Home Office has operated under a veil of secrecy. What has come to light is an increasingly chaotic approach and concerning level of data analytics and sharing.

We have written to the ICO and Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration with our concerns about these practices and sought engagement from the Forensic Science Regulator on issues of quality control. Further, there have been insufficient assurances that extracted evidence is not used in asylum and immigration decisions. As the courts consider the evidence, we hope the various regulators and inspectorates will take a close look at current and past practices.

Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill

The case developed in the midst of heated debates around the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (“PCSC Bill”), which has just emerged from the House of Lords. The PCSC Bill seeks to provide the police, and immigration officers, powers to extract data from mobile phones of victims and witnesses if they have “voluntarily provided” their device and agreed to extraction. PI has previously made submissions to the Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights about why relying on consent in such circumstances is highly problematic, and why this is even more so in an immigration context. PI has repeatedly argued, and has done so again in this case, that the search of a mobile phone, just like the search of a home, should require a warrant.

For more information on the case, please see our case page