“Influencer” ads transparency on social media

The role of social media and search platforms in political campaigning and elections has come under scrutiny.

- As discussions of potential solutions evolve from banning political ads to platforms providing meaningful ad transparency globally, limiting microtargeting of ads, and expanding transparency to ads outside of strictly political ads, it is important also to look at other forms of advertising that platforms play host to.

- Sponsored content and influencer marketing play an important role in discussions of ads transparency, and one that is often overlooked by political ad discussions.

Recently the role of social media and search platforms in political campaigning and elections has come under scrutiny. Concerns range from the spread of disinformation, to profiling of users without their knowledge, to micro-targeting of users with tailored messages, to interference by foreign entities, and more. Significant attention has been paid to the transparency of political ads, and more broadly to the transparency of online ads.

As discussions of potential solutions evolve from banning political ads to platforms providing meaningful ad transparency globally, limiting microtargeting of ads, and expanding transparency to ads outside of strictly political ads, it is important also to look at other forms of advertising that platforms play host to. Sponsored content and influencer marketing play an important role in discussions of ads transparency, and one that is often overlooked by political ad discussions.

Influencer content is oftentimes hard to identify. A 2019 study commissioned by the Advertising Standards Authority looked at what type of advertising disclaimer most resonated with users of social media, specifically Instagram and Twitter. The study found that about 80% of the participants overestimated their ability to correctly identify sponsored content. Only 32% of 18-64-year olds were actually able to identify influence ads as 'definitely an ad'.

The study identified that the most useful types of ad labels include: "Advertisement", "Advert", "Sponsored", and "Ad", but that the position of these labels is important. When #ad was positioned upfront in a post, 35% of participates classified the Instagram post as "definitely an ad", while when #ad was located at the end of a post, only 29% of participants identified it at "definitely an ad". The study summarised that "influencer ads were less likely than brand ads on social media to be identified as "definitely adverts" even when a label was included in or added to the post".

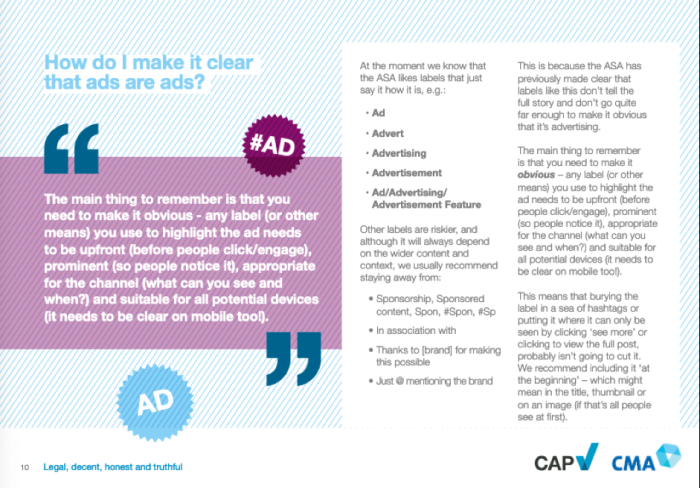

Screenshot from 2019 study commissioned by the Advertising Standards Authority which looked at what type of advertising disclaimer most resonated with users of social media.

In the UK there are three main bodies that work to address influencer advertising transparency: the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), which ensures that ads on UK media comply with the Ad Codes, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), which is responsible for enforcing competition and consumer law and investigating potential breaches, and the Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP), whose members are responsible for writing the Ad Codes.

In some places, such as the UK, regulators are taking action against influencer and sponsored posts that are not fully transparent. For example, a UK Instagram influencer with over 2.5 million followers was investigated by the ASA after not making it clear that some of her posts were actually Flash and Febreze ads.

The UK’s Consumer Rights Act requires social media influencers to be transparent about when they have been paid or given another form of compensation for promoting, reviewing, or talking about a product on social media. In addition, the CAP Code says that "ads must be obviously identifiable as such", meaning that consumers should be able to "recognise that something is an ad, without having to click or otherwise interact with" a piece of content. The three organisations have produced guidance on how to ensure ads are clear and obvious.

Screenshot from 2019 study commissioned by the Advertising Standards Authority which looked at what type of advertising disclaimer most resonated with users of social media.

In the UK there are three main bodies that work to address influencer advertising transparency: the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), which ensures that ads on UK media comply with the Ad Codes, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), which is responsible for enforcing competition and consumer law and investigating potential breaches, and the Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP), whose members are responsible for writing the Ad Codes.

In some places, such as the UK, regulators are taking action against influencer and sponsored posts that are not fully transparent. For example, a UK Instagram influencer with over 2.5 million followers was investigated by the ASA after not making it clear that some of her posts were actually Flash and Febreze ads.

The UK’s Consumer Rights Act requires social media influencers to be transparent about when they have been paid or given another form of compensation for promoting, reviewing, or talking about a product on social media. In addition, the CAP Code says that "ads must be obviously identifiable as such", meaning that consumers should be able to "recognise that something is an ad, without having to click or otherwise interact with" a piece of content. The three organisations have produced guidance on how to ensure ads are clear and obvious.

The CMA has warned however that "hundreds" of influencers are not complying by the rules.

So, what are platforms doing to ensure that their users are not manipulated into taking action without having the full picture of who’s behind what they are seeing? Well, not much.

In 2019, Instagram and Facebook (Instagram is owned by Facebook) banned users under the age of 18 from seeing posts that promote certain weight loss and cosmetic procedures. Instagram also has rolled out a labelling system for branded content on the platform, which includes a “Paid Partnership” tag appearing next to a post. The labels are included with photos and videos in users’ feeds, as well as within Stories – but it’s unclear if this label also applies when an influencer is rewarded in ways other than direct payment. Using Instagram’s labelling system however isn’t compulsory, which has resulted in influencers using labels like #sponcon and #sp, which are very difficult to decipher meaning from, especially if they appear at the end of a post.

Another potential issue with influencer ads transparency on platforms relates to the platforms that include some ephemeral element. Ads on Instagram or Snapchat, for example, can disappear after a certain time, making their regulation more difficult if not impossible. The CAP has warned advertisers about this.

Finally, there have been cases documented where influencers attempted to flout the rules completely. For example, the Guardian reported that Khloe Kardashian shared a post about a hair supplement and captioned it “This is more than just an #Ad because I truly love these delicious, soft, chewy vitamins” which one can say is subverting the meaning of the #ad label.

The Guardian also reported about an example of a “famous British YouTuber has been known to place the word “ad” on the bottom right hand corner of his YouTube thumbnails, conveniently behind YouTube’s timestamps – while his girlfriend posts affiliated links to the products she uses in her videos without revealing that she’s paid every time they’re clicked.”

In sum, there is more research and work to be done to understand how best to ensure that users globally are not being targeted and manipulated in ways that they are unaware of. Platforms play a role in ensuring that users are able to understand why and how exactly they are being targeted with content, and who is paying for it.