Being the target: Ananda Badudu

PI spoke to Ananda Badudu, an Indonesian activist, on his experience of surveillance.

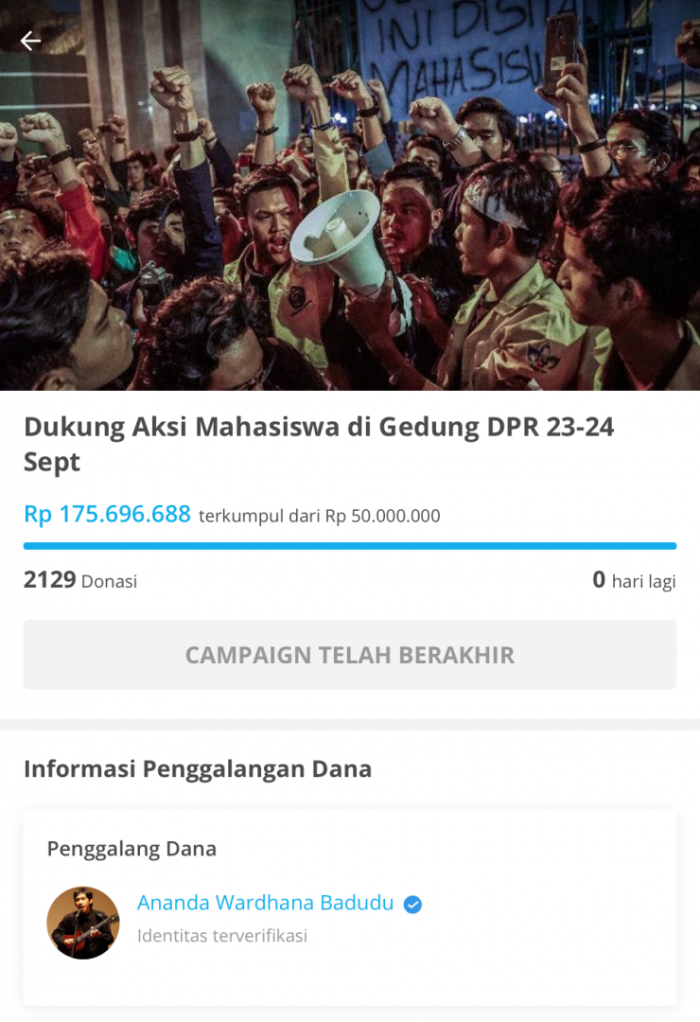

Ananda Badudu is an activist, musician and former journalist. In September 2019, he started a crowdfunding campaign page to support student protesters taking part in demonstrations against the Indonesian House of Representatives.

Qn: Please briefly describe your work and the issues/topics you work on.

I’ve been full-time musician for 2 years. Before that I was a journalist from 2010 to 2016, first at Tempo, then at Vice. In late September 2019, I took part in a crowd-funding campaign in late September 2019 to provide support to civilians taking part in a protest against corruption.

Qn: What is your understanding of surveillance?

Surveillance is a breach of privacy for the purposes of knowing your whereabouts, and watch you without your knowledge.

Qn: What kinds of surveillance or harassment, whether tech-enabled or not, have you experienced?

I was arrested because I led a crowd-funding campaign for a demonstration that took place in late September 2019 in front of the Indonesian Parliament. The crowd-funding campaign aimed to provide logistical and medical assistance to protesters, including the provision of ambulance services and water. The crowd-funding page was open for 4 days, during which we received 175 million ruppia from 2129 people. That’s enough to buy a mini-van car in Indonesia. Me and my team used that money to provide ambulances, bottled water and a car with a speakerphone during the protest. The funds were also used to cover the cost of protesters being hospitalised. That’s what got me arrested.

- In September 2019, a series of protests erupted across Indonesia. The demonstrations, largely student-driven, protested against a law passed by parliament which curbed the authority of the corruption commission, as well as proposed changes to the criminal code which made it a crime to insult the president’s honour and banned extramarital sex.

I anticipated that leading the crowd-funding campaign would get me into trouble, so I chose to have a friend stay with me in the days after the protest. The address of the place I was staying at was not listed on any of my IDs, because it was only a temporary accommodation. I was later told by the concierge that that address had been under surveillance for a few days prior. I do not know how the police got my temporary address our found out that I lived there.

On 27 September 2019, at 04:30 am, the police came to knock on my apartment. I panicked, as I could see that there were five plain-clothed policemen. In Indonesia, plain-clothed policemen are the ones known to handle street criminals. My friend opened the door, and the police told him that they were looking for me and had a warrant for my arrest. While they spoke, I tweeted that I had the police outside my door and that I was going to be arrested for supporting the protests. A few friends came over to make sure that these men were actual policemen. When this was confirmed, I came out to meet them, and was taken to the police station. Luckily, the earlier tweet had got the attention of some NGO friends at Amnesty International, who were willing to meet me at the police station.

When I arrived to the police department, I resisted coming into the interrogation room because I didn’t want to go in without a lawyer. But the police didn’t care about what I had to say, and dragged me to the interrogation room anyway. As they were taking me, I resisted, and the beat me for roughly 10 minutes, during which they kicked, choked and hit me. I assume they did so because they wanted me to be mentally vulnerable ahead of the interrogation to ensure that I was responsive. Even once I got to the interrogation room, I refused to answer any questions. The police got angrier and yelled at me telling me things that were abusive. Eventually three legal defence organisations came to the police station that morning, but the police didn’t allow them to meet me. I was in the interrogation room for six hours without being allowed to see anyone, not even the probono representatives who were there to assist me.

I was released at 11 am that morning. To this day, though I speculate that my arrest was somehow related to the crowd-funding campaign, I have not been told of the reason for my arrest. I have also not been allowed to see my arrest warrant. My legal team was not allowed to see it either. After I was released, I was given a chance to give a statement to the press, which got involved because my tweet about my arrest had gone viral. I gave out a short statement, telling the press that there were many students (at high school, college and university level) who were still being kept at the police station being treated unethically, and who needed more help from the public.

Later I received a letter from the police where they accused me of making false statements - known as “somasi” - and asking me to make a public apology. I was then told by a the police spokesperson, that if I didn’t take back my statement I’d be be arrested again for violating the law. Two days after going home, instead of retracting my earlier statement, I made a press statement to the police saying that I was ready to come to the police department. After that I went into hiding mode for two weeks. I changed my phone number, and got a new mobile phone with a number registered in my friend’s name. I took this measure because in Indonesia you have to register your mobile number, and in order to do so you are required to provide your ID number and your family card, which itself containes information about your family members. You have to provide that information any time you obtain a new mobile number. I don’t know if this information is shared with the police, but regulations about privacy and data in Indonesia are not clear. We don’t have a general data protection law regulating the privacy of the citizens, so it could well be that this information is shared widely without us knowing. We cannot know who holds our data, how it is obtained, and who it is shared with. In my opinion it is possible that the police could be using that data. There have been many incidents which have shown that telecoms providers have sold data to private corporations, so it is possible that this type of data could be wildly circulated without the user knowing.

While I was in hiding, I didn’t use my own phone, or any of my social media accounts for about three weeks. I was scared that they could find me. Eventually the police forgot about me, and I was able to live my life normally.

After reading the news of my arrest, I came to the conclusion that I was released because my arrest had gone viral. The Indonesian police is sensitive about virality in social media, so public pressure had an important role in my release. This is obviously not the case for all who are arrested.

Qn: Were you able to identify the persons or entities behind these attacks? Were they affiliated to the private sector, public sector or both?

It’s difficult to know who is behind the buzzer attacks. Tweets of mine have gone viral on issues besides my arrest. I once found my name and Twitter account mentioned in a Ministry of Defence’s slideshow. The slideshow referred to the “omnibus law”, a controversial law that is about to be legalised in parliament at the government’s behest. The slide itself included my Twitter account, which was categorised as a threat.

Qn: To what activities do you attribute these incidents?

I think it is because of my general activism. I’ve gone viral several times on Twitter by commenting on the handling of the pandemic by the government, for example by criticising the “new normal” government campaign. At some point, one of my tweets was the second most viral in Indonesia. Since my arrest, I have started being more careful before I tweet.

Qn: How has your experience of surveillance and harassment impacted your work?

In some way, it has had a positive impact - and you can see it by the numbers. Three months after I was arrested, my popularity on Spotify went through the roof: I had 50% more listeners and streamers. But not all has been positive. After the arrest, I got a gig at the Corruption Eradication Commission office for an event. I had played for that office several times previously. When I saw the permission request slip - which is compulsory for any events accommodating 100 attendees or more -, I noticed my name was not there. This was unusual. When I asked why, I was told that if my name was there, the police would deny the permit - and therefore they deliberately ommitted my name to obtain the permit.

Qn: How has your experience of surveillance and harassment impacted your personal life?

After my arrest, I became more active in social media, and continued campaigning and criticising the government. When any of my tweets went viral, usually within 1-2 days, I’d get “buzzer” attacks. “Buzzers” are what you could call social media soldiers that attack human rights defenders on social media. In other countries, bots are used, but not in Indonesia - that’s too sophisticated. There’s real people behind those buzzers. But how they operate is still mysterious. What we know now is that they have offices, usually with 3-4 people, and they operate many social media accounts, sometimes going well into the hundreds. Usually “buzzers” are pro-government, and they are outsourced to do the government’s job. M It’s a real thing in Indonesia, and they are quite big here. Often they “dox” HRDs in social media. My friend is a LGBT activist and she often gets doxxed by the buzzers. Another friend is a labour activist and she often gets doxxed too by the buzzers. I haven’t been doxxed myself because I’m a private person, and there isn’t a lot about my private life on internet. Maybe the reason I haven’t been targeted yet by doxxing maybe they don’t have that much on me.

Since I became more vocal on injustice, my family and I have come to an agreement to avoid talking about politics. Many family members support the political party currently in power, so there is room for disagreement.

Qn: Have you ever sought help from the authorities? If not, why not? If yes, what was the result?

Never. We already know that the police are corrupt and there is no justice in law enforcement in Indonesia, especially if you are in the activist circle or the opposition circle. You already know that if you report your case to the police, you won’t be treated rightly. I’m pessimistic about law enforcement here. I would never go to them to seek any help.

Qn: In your country, what are the main obstacles to accountability and/or redress for HRDs?

Corruption. The police is one of the most corrupted institutions in Indonesia. In 2017, an officer at the Corruption Eradication Commission, was almost blinded in an acid attack. It was later found that he attackers were police officers. Initially, prosecutors recommended one-year sentences for each of them. They have now been convicted. In 2019, a Commissioner from the Corruption Eradication Commission was targeted with a Molotov cocktail. No investigations were made.

These incidents have made us all pessimistic. The message is clear: if you oppose the government, you’re at risk of being attacked, whether online or face-to-face.

The reality however is that the police are everywhere, and they have gained a lot of the power since the ruling political party came to power. And to an extent, activists depend on them. If you want to have a protest, you have to go to the police for permission - even though the police is the tool of the state to repress critics. It is a hard time for Indonesian activists right now because the police is getting more repressive. And to top it off, they are unlikely to be held to account. Last year, one of the active police generals became head of the Corruption Eradication Commission.