Photo by Mohammad Rahmani on Unsplash

Over the last 20 years, vast data-intensive systems were deployed in Afghanistan by national and foreign actors. As we highlight some of these systems we present our concerns as to what will happen to them.

Photo by Mohammad Rahmani on Unsplash

After almost 20 years of presence of the Allied Forces in Afghanistan, the United States and the Taliban signed an agreement in February 2020 on the withdrawal of international forces from Afghanistan by May 2021. A few weeks before the final US troops were due to leave Afghanistan, the Taliban had already taken control of various main cities. They took over the capital, Kabul, on 15 August 2021, and on the same day the President of Afghanistan left the country.

As seen before with regime changes in other countries, the whole digital infrastructure is now at risk of falling into the hands of a new entity - bringing with it major risks and potentially huge consequences for how the data will be used, for what purpose, and by whom. Control of this infrastructure will impact millions of people immediately and in the long-term.

Over the last 20 years, vast data-intensive systems were deployed in Afghanistan by national and foreign actors as part of developmental as well as security and counter-terrorism measures alongside a broader security and surveillance infrastructure.

Under successive administrations in Afghanistan, changes were made to the national ID system including format and the data it contains. The Tazkera initially started as a paper-based document, and it is the national identity document issued to all citizens of Afghanistan. It serves as proof of identity, residency and citizenship. An electronic version of the Tazkera, the e-Tazkira, was launched in 2018 before also developing it further to include biometric information.

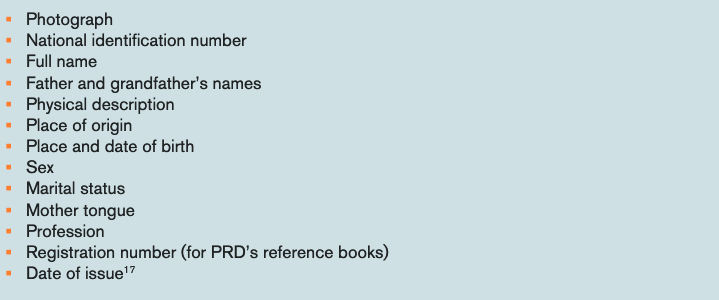

Whilst these different forms of the document remain in circulation, it was reported that most ID cards today contain the following information:

Source: Samuel Hall and the Norwegian Refugee Council, Access to Tazkera and other civil documentation in Afghanistan, 2016, pp. 16

The roll out of the system faced some controversies including disagreements between what consitutes citizensip vs ethnicity as it would appear on the card, and also there have been huge issues of exclusion with women unable to obtain an ID card, amongst others. These were the problems Afghans were already facing with previous regime, there are only unknowns as to what is going to happen next.

Over the years the development of e-Tazkira has benefited from funding and support from different actors. It was funded from the United States who withdrew in mid-2015 when no progress had been made), and by the European Union until 2016 when they withdrew saying they cannot support identification cards that designate ethnicity. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) has been involved in the implementation phase of the e-tazkira. It was also recently reported that the system was in a process of being updated as part of social inclusion programme funded by the World Bank. However as of 2020, the ambition of the e-tazkira had not yet been fully realized, although the Afghan administration was until recently continuing its efforts, looking to India’s controversial/privacy invasive Aadhar program for guidance.

Moving forward the very existence of such a biometric database which requires effective governance and maintenance is concerning given the instability of the situation in Afghanistan. Even more so as the officially recognised government needed extensive external financial and technical support to even see this initiative through. What will happen now that it’s unclear if the Afghan administration in charge of the e-Tazkira may no longer be in place, and whether external support will still be around?

In addition, there are inevitably serious concerns about how the biometric data it contains could be used for malicious identification by entities emerging in power to ascertain their own control. The data stored could reveal very sensitive information, from socio-economic status to gender and ethnicity - easily derived from father and grandfather’s names and mother tongue. This information might be used by entities to identity and target opponents.

Over the years, though, there have been evidence of the risks posed by the development of biometric databases in Afghanistan. They were starkly illustrated when local journalists reported in 2016 and 2017 that Taliban insurgents were stopping busses and using biometric scanners to identify and execute any passengers who were determined to be security force members. It is not clear where the Taliban got the biometric data from.

To read more about the deployment of digital identity systems across the world and the implications for people and the enjoyment of their fundamental rights, we invite you to visit our “Demanding identity systems on our terms” page and explainers.

The support provided by the international community over the last 20 years, also, included funds and support to build up the capacity of Afghanistan “to prepare for, observe, administer, and adjudicate elections”. Part of the UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA)'s mandate has been the provision of support to Afghanistan’s electoral authorities and their work.

Afghanistan’s first national voter registry that was created in 2018. Whilst the very existence of such a system was deemed a success, it brought with it huge concerns about exclusion, as it required the presentation of the e-Tazkira which not everyone had, as noted above. But also electoral fraud seems to be tied to identity fraud because there is no effective way to prevent or detect efforts to register with fraudulent tazkeras. Finally, there were further concerns for the safety of voters as it was reported that the Taliban had “established checkpoints on major roads into multiple provinces to check for voter registration stickers, and threatened to kill those found with them”.

In order to tackle election fraud, they introduced biometric voter verification systems in every poll station to take the fingerprints and photo of every voter and record the time they cast their ballot. These systems were hastily introduced in 2018 parliamentary polls and were reportedly ignored or abandoned. The German firm, Dermalog, was contracted to provide the system and following the 2019 Presidential election they confirmed that 1.9 million votes had been biometrically registered. And whilst the biometric system was mean to tackle fraud and encourage voter confidence, the Independent Election Commission confirmed that an intrusion into the Data Server room of biometric devices had occurred, and the turnout was the lowest in any election since 2004.

Similarly to the e-Tazkira database, there are concerns not only about the maintenance and care of the database itself, but also to prevent it from decaying into an outdated vulnerable database which could potentially expose individuals if their data is not safe and secure and is accessible by entities with an agenda to use this information for political gain and control.

To find more about the risks associated with voter registrations systems we invite you to look at our check list.

In Afghanistan, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) developed its biometric program in confluence with US military operations. Its expansion was tightly linked to the goals of military commanders during the “War on Terror”: to distinguish insurgents and terrorists from the local civilian population. After testing biometric prototypes in Afghanistan in 2002 and in Iraqi detention centers in 2003, the Department eventually mandated that fingerprints, facial photographs, and DNA must be collected from all its detainees worldwide.

To collect and store this data, the DOD launched its Automated Biometric Identification System (ABIS) in 2004, a database that serves as a central repository for all biometric data collected by the military. Entries in the ABIS database adhere, for the most part, to the 13-point biometric standard (10 fingerprints, 2 iris scans, 1 facial photograph). The majority of the ABIS database is comprised of identities collected from people in Afghanistan (and Iraq): detainees, prisoners of war, people applying to work on US military bases or the Iraqi police, recipients of microloans, and anyone whose identity could be considered a national security concern. The most recent statistics available on the DOD Defense Forensics and Biometric Agency website state that the ABIS database currently contains over 7.4 million identities. It is estimated that approximately 3 million of those entries were collected in Iraqi and over 2.5 million in Afghanistan.

In Afghanistan, biometric information was collected from suspected insurgents, dead and live enemy combatants, detainees, military contractors, applicants seeking to join the Afghan police or army, as well as other individuals. Additionally, as reported in 2010, the DOD began integrating its forensic and biometric capabilities, lifting latent fingerprints from improvised explosive devices (IEDs), weapons, and documents and entering them into the ABIS database.

Recommendations in the “U.S. Army Commander’s Guide to Biometrics in Afghanistan” advised military officials to integrate biometrics collection into all of their operations, to “create a sense of urgency” around biometrics collection, and “be creative and persistent in their efforts to enrol as many Afghans as possible”. It was reported that at the national borders, where US forces arbitrarily stopped and biometrically registered people coming into Afghanistan, by 2011, randomly selected border crossers made up 10% of all biometric enrolments in Afghanistan. In areas with high insurgent activity, all “military-aged males” were compulsorily registered. The Economist reported that Afghani men were being pulled out of mosques, their homes, and public transportation in order to have their fingerprints and irises scanned.

A key concern around these processing activities of biometric data as we recently highlighted is that the DOD’s biometric programme was developed and implemented without prior assessment of its human rights impact and without the safeguards necessary to prevent its abuse. Its whereabouts and current use remain unclear. And a further area we are concerned about is the international data sharing activities that have been ongoing for decades and which continue to be in place today.

In terms of the current situation which is unfolding in Afghanistan, it is unclear what is happening to the soft and hard infrastructure being left behind by the Unites States and other foreign powers, and if and how these are being secured from being accessed by entities emerging with power with their political and security agenda. Initial reports have started to emerge about the Taliban having seized US military biometric equipment known as HIIDE, for Handheld Interagency Identity Detection Equipment. As we reported recently, HIIDE was provided in 2007 after L-1 Identity Solutions was awarded a $8.3 million contract by the US military.

This section is extracted from our case-study on the use of biometric in counter-terrorism in Afghanistan.

In addition, the international community provided support to reform and strengthen the security and intelligence infrastructure of the Afghan government.

This saw the deployment of various surveillance systems including the intercept programme to provide for a judicial process to obtain warrants and monitor communications of suspected criminals and terrorists. The infrastructure to enable such wiretapping and monitoring of calls was provided, partially at least, by the US company Special Operations Technology Inc. which was awarded a $79 million contract modification “to install, operate, and maintain the lawful intercept equipment and support equipment at various locations around Afghanistan”.

Further investment led to additional tools being made available to the army including the National Information Management System (NIMS), which allows military units across Afghanistan to share real-time intelligence and provides decision makers the ability to make informed and time-sensitive decisions.

Whilst information remains limited, a £26 million programme managed by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office funded “Capacity building in areas of police intelligence and targeting” and was finalised last year.

As a result there are now serious concerns that some surveillance technologies - which may have been initially introduced as part of surveillance practices subject to safeguards - will now be used for human rights violations.

There have also been reports that the US Embassy in Kabul has been contacting local partners asking them to take steps to delete data collected from social media, including photos and other information "that could make individuals or groups vulnerable”. Similar action is also being taken by the US State Department and NATO amongst others.

What these measures highlight is the power associated with social media data and digital data trails, that is data generated through peoples’ use of social media. This data on its own and when associated with other sources, such as metadata, provides valuable intelligence to others, who want to monitor, profile and identify potential targets.

The concern today in Afghanistan is how such data may be used to identify, track, target and expose to repression individuals and groups who have been supporting and contributing to the efforts and programmes of the international community in the last 20 years. The concern of retaliation also extends to those who have been writing, documenting abuses by various actors, as well as to target individuals and groups which have embraced views, behaviours and ideologies which do not align with those entities who may end up in power.

The creation of vast data-intensive surveillance systems carries with them a number of risks that range from the security of the data and the infrastructure to it being used for other purposes.

Afghanistan is at a turning point. The Afghan government, with all its prior weaknesses and flaws, is on the brisk of collapsing with its President having left the country, and new entities are coming to the forefront to establish themselves as in power. In such context, it is unclear how any of those parties will proceed with existing governance structures or new ones, and how the systems in place today will be used, misused and abused for political control, economic gains or for security purposes.

The governance structure in place until today surrounding the use of these systems was already weak with poor regulatory and legal frameworks, and weak monitoring and oversight mechanisms. As current events unfold, whatever little safeguards and protections were in place they may be reduced to nothing.

Below we outline some of the risks which may emerge but this is an exhaustive list and much remains to be seen depending on how the situation unfolds.

Often referred to as mission creep, it describes the re-purposing of data which results in the data being used for other purposes outside of what the data was collected for. For example, access to biometric databases may be granted to law enforcement and security agencies in the name of national security and counter-terrorism, even in instances where those databases were designed for purposes unrelated to counter-terrorism and prevention or investigation of crimes.

We’ve seen this countless times with both digital identity systems or surveillance systems being repurposed for uses not intended at the point of collection. Notoriously, IBM’s punch card system supposed to be used for the German census was subsequently used by the Nazi’s to identify Jews. More recently, the Europe Union’s EURODAC biometric database meant to strictly be used for asylum procedures is to be used for law enforcement, while numerous counter-terrorism powers are used for investigating low-level offences and surveillance capabilities used to crack down on dissent.

Whilst tracking and identification are often a core justification of many surveillance systems to identify threats and individuals with malicious intentions. Such mechanisms set-up the ability to track, identify, and re-identify practically anyone whose data has been collected either as part of formal data processing activities leading to centralised databases to monitoring systems tracking individuals and groups online through their digital data trail, sometime even in real time.

When biometric systems fall into the hands of other actors such as what is reported to have happened in Afghanistan, there is a risk that the biometric information may be used to identify individuals. Biometric information is inherently identifiable, even after other information such as the name of the individual or the location of where that biometric data was collected has been stripped.

Fingerprints, facial features and iris scans are unique to an individual; such information contains identifying information which can be used to re-identify individuals. There are already fears this is happening in Afghanistan at the moment. These fears are not irrational as there have been reports that in the past, the Taliban unlawfully breached the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) biometric information system and used the information to target security personnel by tracking digital history in Kunduz Province.

And when the same thing happens with communications surveillance systems it means that systems which may have been part of lawful surveillance programmes for law enforcement purposes ends up being used to track and identify individuals in arbitrary and unlawful ways. On numerous occasions human rights defenders, journalists, and activists as well marginalised groups and communities have fallen into this net of unlawful surveillance. What one regime identifies as a threat to national security may not be the same as the next one as we’re seeing unfolding in Afghanistan.

Complex IT systems are inherently vulnerable to intrusions or data breaches. There are numerous high-profile examples of ‘secure’ IT systems being breached. Security often being an after-thought and not enough is done to invest in security by design and default from the onset. Unless these systems are maintained, audited and updated, they will inevitably become vulnerable. This ends making the job of those wanting to get this data a easier.

Also unlike a password, an individual’s biometrics cannot be easily changed and biometric data can identify a person for their entire lifetime. Biometric data breaches seriously affect individuals in several ways, whether identity theft or fraud, financial loss or other damage. In Afghanistan, access to biometric systems left behind by the government in the form of digital identity system, or other pose grave harm to the people whose information is stored on those databases.

The priority given the tragic developments unfolding in Afghanistan is to ensure that people are protected, and that the systems put in place over the last 20 years by both Afghan authorities and foreign actors are not used to betray individuals, expose them to risk and serve as hit list by the Taliban or other entities on a power grab process.

Those with roles and responsibility in the deployment, maintenance and funding of some of the digital systems in Afghanistan must step up to minimise the damage.

Those responsible for deploying these systems: They must ensure that that both the data and the infrastructure that stores it is safeguarded from potential abusive uses.

Foreign entities operating in the country: This includes some of the global funding institutions, donors and international development and humanitarian agencies, they must take steps to secure their data and their infrastructure immediately.

Industry: Companies, including telecommunication operators and social media platforms, must take action to secure their data, products, devices and infrastructure urgently in order to prevent further harm to their users. Behing every phone number and social media account is a person that has a right to be protected.