Emergency Social Protection responses to Covid-19 around the world

Privacy International has been researching how emergency welfare responses have been handled in different countries in light of the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite the variety of socio-economic and political contexts of the countries researched, PI has found that a lot of them share common concerning elements along the benefit disbursement process, namely the automation of eligibility processes, lack of transparency, excessive data collection, security issues in disbursement methods and more.

- Emergency welfare responses to the Covid-19 crisis have seen governments increasingly relying on automated and opaque eligibility processes and forsaking privacy considerations and inclusion.

- Welfare benefits systems must be implemented in such a way that they comprehensively respond to the needs of the most vulnerable while upholding individuals' human rights.

The global COVID-19 health crisis not only induced a public health crisis, but has led to severe social, economic and educational crises which have laid bare any pre-existing gaps in social protection policies and frameworks. Measures identified as necessary for an effective public health response such as lockdowns have impacted billions workers and people's ability to sustain their livelihood worldwide, with countries seeing unprecedented levels of applications for welfare benefits support, putting ever more pressure on governments to act quickly and effectively.

On approach taken by governments around the world has fast-tracked emergency relief legislation for welfare programs, which rightfully seek to address the needs of those most vulnerable. At the same time there is a growing understanding that Covid-19 impacts people differently depending on their class, race, gender and legal status, with heightened impact on minorities. This brings additional challenges when implementing these measures, that can come at a costly price for individuals who end up being excluded or forgotten. As the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty put it, these support packages have left the most vulnerable "short-changed or excluded".

In this context PI has conducted research looking into the introduction of new programmes in response to Covid-19, the novel eligibility criteria devised for these programmes, the methods used for the rapid identification of potential beneficiaries and where such methods fall short. The research looks at the responses to the pandemic of 10 countries around the world, focusing in measures targeted at groups recognised as being in a particular situation of vulnerability, rather than looking at measures targeting the majority of the population; and also looking into how these beneficiaries are defined, identified and serviced in a crisis situation.

On eligibility

Who's eligible and how is this decided?

The first big challenge when designing such emergency welfare programs is to identify the individuals who will benefit from them, and to define eligibility criteria. Transparency should be ensured throughout the process, both regarding the disclosure of measurable criteria and where the lines are being drawn to aid someone and leave another one out. Not disclosing how these programmes operate is an obstacle that stops people in vulnerable and precarious situations from having information they need to be able to understand and challenge these systems in cases of exclusion.

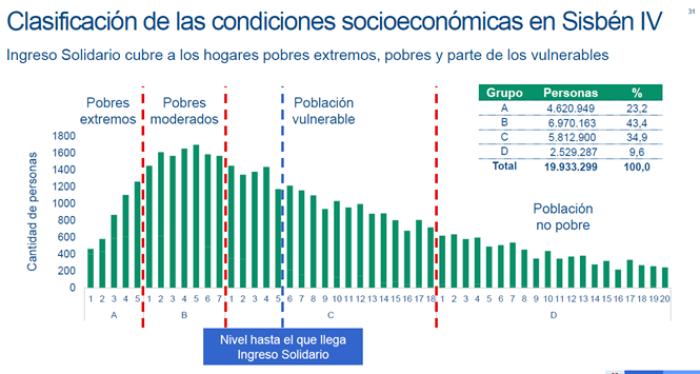

In Colombia for example, the National Development Office set up Solidarity Income (“Ingreso Solidario”), an unconditional cash transfer system for 3 million citizens in just two weeks which made use of all kinds of administrative records and data managed by both private and public actors to compute and assign scores to every person and group the Colombian population in 4 segments.

While the score criteria were made public, people were completely left in the dark as to what these scores meant in the first place and because some of the databases used were completely unknown to the population affected, people were not able to access or rectify any outdated or inaccurate information used to make a decision on their situation. After the government published the list of beneficiaries and after numerous citizens reporting being excluded, it was concluded there were nearly 17,000 records with inconsistencies. Because the system is a "black box" it was - and is - impossible to know how many people were unfairly excluded in the crosschecks between different databases.

In Myanmar, the government similarly disbursed payments to households in poverty without disclosing the eligibility criteria or the relevant factors relied upon to calculate the amount received by any recipient household. Myanmar's Covid-19 Economic Recovery Plan (known as CERP), launched in April 2020, announced the introduction cash transfers of “an appropriate amount (…) to most vulnerable and affected households” through mobile cash transfers. However, no clarity was ever provided as to how the most vulnerable and affected were identified, and the basis on which the "appropriate amount" was calculated.

Other countries have taken similar routes, holding onto the idea of a shiny innovative solution while leaving their populations in the dark about how these algorithms make decisions.

In Nigeria, the Federal Government’s COVID-19 Cash Transfer Project which aimed to lift "the urban poor" affected by the pandemic out of poverty was the first strategy to be developed and tested in the Sub-Saharan Africa region. According to official statements this solution relies on methods such as satellite remote sensing technology, machine learning and big data analysis in order to identify potential beneficiaries. To start, the relevance of these methods to identifying those in need was not explained. However, more worryingly, nothing was made public regarding the criteria utilised to select who this benefit was targeting, which makes it impossible to scrutinise and audit. The pride in being the first country in the region to deploy such a solution should come accompanied by additional safeguards and processes to ensure the solution is adequate and inclusive before it is innovative.

It is also worth highlighting two other countries where beneficiaries were left with no clarity on how their living situations were concretely assessed. In Mozambique, the government decided to identify priority areas by using the MultiDimensional Poverty Index mapping. This index combines social and economic indicators and relies on the data gathered in the most recent census as well as high resolution satellite imaginary of urban poverty maps. In this case, the vulnerability criteria used by the National Institute of Social Action to identify potential beneficiaries was made public but still an independent observer stated that only 61% of beneficiaries knew why they had been enrolled. Similarly, the observer highlighted ongoing complaints about the lack of information on the program including who’s eligible, how much they’re entitled to and with what periodicity the benefit is to be distributed. Similarly, a welfare benefit introduced by the Peruvian government not only relied on unclear eligibility criteria, but has been shown to exclude many. Within the "Stay at Home" program, the Peruvian government identified eligible people through the National Household Register, which categorises households into different socioeconomic bands. Among other factors, households categorised by the Register as being in poverty are deemed eligible to the benefit. However, in a similar fashion to Colombia's case, the criteria used to define poverty are not publicly available, making it difficult for people to assert their entitlement to the benefit and leading to individuals being deemed not eligible despite being in a situation of poverty.

Data-intensive methodologies

After defining the eligibility criteria, governments must ensure that they correctly identify vulnerable populations. For some governments the way to take this task forward was to collect and make use of as much data as possible.

A very clear example of this is the previously mentioned "Ingreso Solidario" in Colombia for which the Government used data collected and managed by private and public actors. Such databases have different levels of quality, and some were unknown to many Colombians. Through data-sharing arrangements across 34 public and private databases, the government cross checked the previously collected information with information in these dozens of databases to find inconsistencies and exclude anyone deemed not to require social assistance. By relying on cross-checking databases to “find” people who are in need, this approach depends heavily on enormous data collection, and it increases government’s reliance on the private sector as well as pulling people away from understanding or challenging the system put in place.

In Nigeria, the government states that its response program makes use of a wholly technology-based approach and believes it is set to achieve end-to-end digital foot-print in cash transfers for "the urban poor". These statements raise concerns about the nature and quantity of data being processed to determine eligibility, as well as the quality of eligibility determinations, as it would appear that recipients of welfare support are identified solely based on automated decision-making without any human intervention or assessment.

The Angolan government sees the social protection program in support of people affected by the Covid-19 pandemic KWENDA as a way to increase banking and digital inclusion for populations. This digitisation includes the creation of a centralised database under the Unique Social Register, which gathers the data of citizens living under poverty and vulnerability. In July 2021, the Angolan government announced that they were in a phase of "data validation", where government teams visit neighbourhoods with "systemically generated" provisional lists of beneficiaries. The government describes these visits as an opportunity for people to learn if their name is on the beneficiary list or not, but the eligibility criteria and the way these lists are put together remain undisclosed.

In Lebanon the government commited to reaching 147,000 Lebanese households with emergency cash-transfers supported by the World Bank. For households to be eligible for aid under this programme they would have to: be Lebanese, be assessed as living below the World Bank’s “extreme poverty line”, and belong to “pre-defined socially vulnerable categories”. One of the disbursement conditions set by the World Bank is that the Lebanese government must undertake a “verification process” of all applicants (i.e., households) that are selected to receive emergency social assistance. As entering a person’s home in order to assess whether or not they meet a poverty score is in itself a serious interference with a person’s rights to private and family life, it is not clear why alternative, less intrusive means-testing methodologies were not adopted. For example, relying on official data which analyses urban and rural poverty across Lebanon. Additionally, more than a year and a half into the Covid-19 pandemic, this form of what was meant to be “emergency” social support still had not yet been disbursed. From both a social protection perspective and a human rights perspective, this calls into question the efficacy of “home visits” as a means of verification prior to disbursal.

In Jordan, the government worked with UNICEF to add new vulnerable households to Hajati, a cash transfer programme that had already been running since 2017. This program aims to support vulnerable households with monthly 'no strings attached' direct cash transfers, in its majority targeting Syrian refugee families in Jordan. Nonetheless, in order to access this monetary aid, households registered with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) need to had to have their iris’ scanned for authentication purposes. It is unclear if this process is mandatory of if people can opt-out and choose to be identified in some other way. This process means that at some point in time, beneficiary biometric data has to be collected and uploaded onto databases that users know very little about. It is another example of data-intensive systems being implemented where users are not in full control of their data and where their data is used as a pre-requsiste to access an essential benefit. In this case in particular, because we are dealing with unique biometric data, it is also worth highlighting the potential problems coming from keeping such type of databases on refugees or other vulnerable populations as a risk on its own. As we have seen happening in the past, the consequences if such biometric databases fall in the wrong hands can be catastrophic and there is very little one can do once it happens as biometrics are immutable like that.

The Jordanian government also relied on a system called “Takaful”, run by the National Aid Fund, to disburse emergency cash payments. “Takaful” was developed to have "an automated capability to update the administrative information on households and individual members, including data on formal working status and wages as well as other formal income (e.g. pensions) and assets, which are obtained automatically from the national Social Security Corporation and other public institutions." The fact that there are government databases which automatically share information across public institutions and are then relied on to make decisions about welfare entitlement makes it imperative to also have safeguards to ensure accuracy, rights of appeal and data security.

The wealth of data potentially involved in choosing beneficiaries, together with the nature of decision-making, raises legitimate questions about compliance with data protection frameworks and other human rights obligations. Specially when relying on vague and imprecise technologies, it becomes difficult to assess their effectiveness and suitability for identifying eligible claimants. Further, there can be concerns as to the security standards observed once eligible beneficiaries are identified.

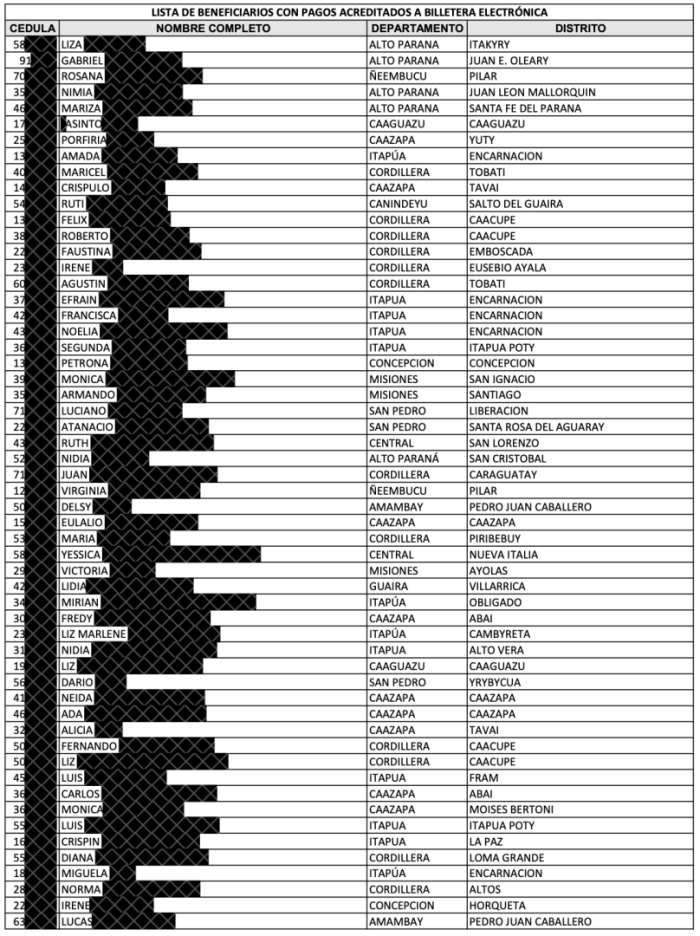

In Paraguay there have been documented concerns regarding the use of unsecure online platforms for its Ñangareko Programme, aimed at those affected by Covid-19, such as the fact that Ñangareko's website didn't make use of the HTTPS protocol which provides users with an assured secure connection to the website over HTTP. Besides this, concerningly, the list of beneficiaries was made available in an Excel format for anyone to access from a Google Drive and from the government website, which made the names, ID numbers and districts of beneficiaries publicly acessible to anyone.

The Excel spreadsheet (see screenshot above) comes to a whopping 3,525 pages, with the personal details of more than 205,000 people. At the time of writing, 20th May 2022, the Excel spreadsheet continues to be publicly available.

The beneficiary list of another assistance programmes called Pytyvõ is also available online in the same format.

In Mozambique, throughout the roll-out of its Covid emergency programme, there were reports of people being threatened and harassed over the phone by individuals affiliated with criminal gangs demanding that benefit claimants hand in the phones to which the benefit was linked. It is not clear how these people got hold of claimants' phone numbers, but it stresses the point above regarding the necessity to adequately protect beneficiary data.

How are these benefits distributed?

Following identification of beneficiaries come decisions on disbursement and the ways in which people are able to access their benefits.

A lot of countries relied on digital Cash-transfer Programmes (CTPs), such as mobile money, for this purpose. These methods have been presented as ways to provide "accountable and secure transfers" and promote inclusion of segments of the population that might be excluded by traditional cash delivery methods as the growing use of digital technologies and connectivity is rendering previously "invisible" people "visible" to financial institutions and governments. Further, in light of the pandemic, these solutions rightly prioritised public health by allowing beneficiaries to receive their benefits remotely without having to risk exposure to coronavairus.

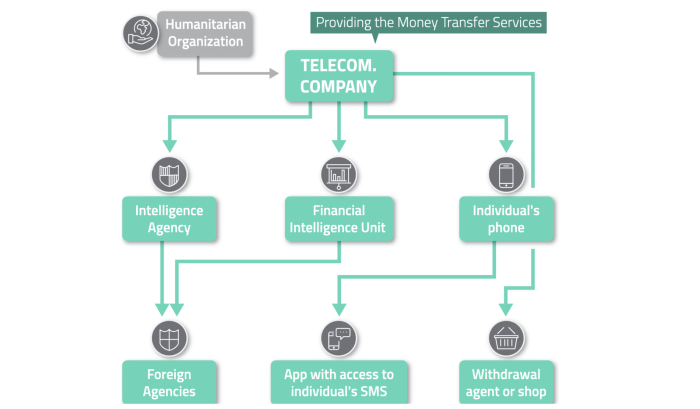

However, apparent easier access and identification also carry risks which must not be ignored. The use of digital technologies for CTP often requires the involvement of numerous, non-humanitarian third parties such as domestic and international mobile network providers including, in some circumstances, financial institutions and financial intelligence units.

Telecommunications providers have become central to CTP initiatives. Such is the case of Kwenda in Mozambique and its reliance on Vodafone as a service provider. In Honduras, an unnamed third-party, privately-owned electronic wallet platform was used to disburse the Covid-19 emergency benefit which raises even further questions regarding transparency about who gets access to sensitive data on beneficiaries' life situation, especially when such third parties primarily function as commercial entities operating for profit, insofar as there is little information as to whether data processed for CTP purposes is kept separate from, or interacts with, their broader range of operations.

When conducting mobile money transactions, the relevant telecommunications service provider can store data such as the sender’s and recipient’s phone numbers, the date and time of the financial transaction, and the transaction ID. This was, for example, the case with M-Pesa in Kenya.

In Pakistan, the government's welfare agency contracted EasyPaisa, an e-banking platform owned by Telenor Pakistan, to disburse pandemic benefits. However, as research by PI partner Digital Rights Foundation found, EasyPaisa's privacy policy states that it collects, in addition to the CNIC and family information, computer browsing information, IP addresses as well as information about buying patterns and behaviours. One is hard-pressed to understand how this information could be relevant to the disbursement of benefits.

By introducing a third-party in the actor chain there is a loss of control over the data collected and the metadata generated by the CTP. This data can then be used for non-humanitarian purposes (e.g. to profile potential customers) and it can also be shared with external parties out of legal obligations or through partnership agreements. It becomes essential to transparently inform beneficiaries on what data is being collected and shared, with whom, for what purposes, as well as the inherent risks of this data collection/sharing and accessible ways to rectify one's data.

Additionally, making use of insecure and outdated communication protocols such as SMS should be avoided where possible as using SMS as an underlying communication protocol opens way for malicious actors to scam and digitally impersonate legitimate beneficiaries in order to claim their benefits instead. The ease with which SMS messages can be intercepted has been demonstrated countless times in the past. In Sierra Leone, cash recipients are selected if they score 7 out of 10 from an undisclosed score matrix assessing areas of potential vulnerability and if a person is deemed eligible they get notified via SMS which allows them to collect a cheque that they must hand over for encashment at a local bank.

For example, in Colombia, where a SMS notification system was also used for the disbursement of pandemic benefits, recipients of the benefit reported receiving SMS purportedly sent by the government's welfare agency with a link to an online form which requested their personal details. This prompted the welfare agency to warn recipients about these phishing attempts on social media, reminding them to verify information through official government communication channels under the gov.co domain.

Finally, although CTPs can promote digital inclusion of populations they heavily rely on this inclusion as a condition for successful benefit disbursement. This inclusion should in no case be taken for granted under the risks of excluding those who are "invisible" to the eye of the state in the first place.

Lessons learned

Welfare responses are not only a necessary, but a vital element of a comprehensive government response to the pandemic. Overall, the push from governments to rapidly scale up welfare coverage in a situation of crisis is a positive development.

However, as the dust starts to settle on Covid-19 welfare responses, we take stock of the lessons learned.

- Eligibility criteria should be publicly available and easily understandable. Heightened transparency and explainability of eligibility criteria enables individuals to challenge decisions made by the relevant public authorities on their eligibility for benefits.

- Individuals and/or households seeking to avail themselves of welfare benefits should be meaningfully integrated in the decision-making process, and be provided with sufficient information so that they have a full understanding of data processing involved as well as any rectification mechanisms to ensure that their data can be accurate and up-to-date.

- While disbursement methods which diminish the likelihood of exposure to coronavirus by welfare beneficiaries are welcome, in-person or non-digital alternatives should be maintained for those individuals who do not have access to the devices. Such alternatives should be accessible and inclusive.

- Governments should ensure that any personal information regarding eligible beneficiaries is kept confidential, and in any event not shared with third parties without the explicit consent of the individuals concerned. Personal data gathered in the context of welfare applications should be used only for the purpose for which it was initially processed to prevent abuse and mission creep.

- Commercial entities involved in the disbursement of welfare benefits should provide guarantees that the data processed in that context is kept separate and isolated from their ordinary activities in order to avoid a conflict of interests.

- Governments should clarify the basis on which any private sector companies are involved in the disbursement of benefits (e.g. digital wallet and e-banking platforms), from how they are initially selected, i.e. the procurement process, to the data that they have access to, and how that data could be subsequently used. PI has developed public-private partnerships safeguards, which we encourage government actors to observe.

- Any personal data categories used to identify beneficiaries should be clearly described, as well as the specific purpose for which each category is used. Any automated processes used in the determination of eligibility should be disclosed, as well as the consequences of the automation, and the level of human involvement in relation to those consequences.